My Bloody Valentine (band)

My Bloody Valentine are a shoegaze band formed in Dublin in 1983. Since 1987, its lineup has consisted of founding members Kevin Shields (vocals, guitar, sampler) and Colm Ó Cíosóig (drums, sampler), with Bilinda Butcher (vocals, guitar) and Debbie Googe (bass). Their music is best known for its merging of dissonant guitar textures, androgynous vocals, and unorthodox production techniques. They helped to pioneer the alternative rock subgenre known as shoegazing during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

My Bloody Valentine | |

|---|---|

My Bloody Valentine in July 2008. From left to right: Debbie Googe, Colm Ó Cíosóig and Kevin Shields. | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Dublin, Ireland |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1983–1997, 2007–present |

| Labels | |

| Website | mybloodyvalentine.org |

| Members | |

| Past members |

|

Following several unsuccessful early releases and membership changes, My Bloody Valentine signed to Creation Records in 1988. The band released several successful EPs and the albums Isn't Anything (1988) and Loveless (1991) on the label; the latter is often described as their magnum opus and one of the best albums of the 1990s. However, they were dropped by Creation after its release due to the album's extensive production costs. In 1992, the band signed to Island Records and recorded several albums worth of unreleased material, remaining largely inactive.

Googe and Ó Cíosóig left the band in 1995, and were followed by Butcher in 1997. Unable to complete a follow-up to Loveless, Shields isolated himself and, in his own words, "went crazy". In 2007, he announced that he had reunited with his bandmates, and My Bloody Valentine subsequently embarked on a world tour. Their long-delayed third studio album, m b v, was released in 2013.

History

1978–1985: Formation

In 1978, Kevin Shields and Colm Ó Cíosóig were introduced to each other at a karate tournament in South Dublin.[5] The duo became friends in what has been described as "an almost overnight friendship"[6] and later formed The Complex, a punk rock band, with Liam Ó Maonlaí, Ó Cíosóig's friend from Coláiste Eoin.[7] The band, who performed "a handful of gigs" consisting of Sex Pistols and Ramones songs, disbanded when Ó Maonlaí left to form Hothouse Flowers. Shields and Ó Cíosóig later formed A Life in the Day, a post-punk trio, but failed to secure performances with more than a hundred people present.[5] Following A Life in the Day's dissolution, Shields and Ó Cíosóig formed My Bloody Valentine in early 1983 with lead vocalist David Conway. Conway, who performed under the pseudonym Dave Stelfox, suggested a number of potential band names, including the Burning Peacocks, before the trio settled on My Bloody Valentine.[4] Shields has since claimed he was unaware that My Bloody Valentine was the title of a 1981 Canadian slasher film when the name was suggested.[8]

My Bloody Valentine experienced a number of line-up changes during their initial months. Lead guitarist Stephen Ivers and bassist Mark Ross were recruited in April 1983 and the band would often rehearse near Smithfield and Temple Bar in rehearsal spaces owned by Aidan Walsh. Walsh, who booked some of the band's early performances, said the rehearsals were "too noisy" and "crazy" that "next door were giving out hell".[9] Ross left the band in December 1983 and was replaced by Paul Murtagh, who left the band in early 1984. In March 1984, Shields, Ivers and Conway recorded the band's first demo on a four-track recorder in Shields' parents' home in Killiney. Shields and Ó Cíosóig overdubbed bass and drum tracks at Litton Lane Studios, and the tape was later used to secure a contract with Tycoon Records.[10]

Soon after recording the demo, Ivers left My Bloody Valentine and Conway's girlfriend, Tina Durkin, joined as a keyboard player.[6] Around this time, Conway, on the suggestion of Shields, contacted Gavin Friday, the lead vocalist of the post-punk band Virgin Prunes. According to Shields, Conway approached Friday in Finglas, asked him for advice and was told to "get out of Dublin."[11] Shields agreed with the advice, commenting in January 1991 that "there was no room for us" in Ireland; Ó Cíosóig explained that the Irish music scene was not receptive to their style.[12] Friday provided the band with contacts that secured them a show in Tilburg, Netherlands. The band relocated to the Netherlands after the show and lived there for a further nine months, opening for R.E.M. on one occasion on 8 April 1984. Due to a lack of opportunities and a lack of correct documentation,[6] the band relocated to West Berlin, Germany in late 1984 and recorded their debut mini album, This Is Your Bloody Valentine (1985). The album failed to receive much attention and the band returned temporarily to the Netherlands, before settling in London in the middle of 1985.[13][14]

1985–1986: Independent releases

Following their relocation to London in 1985, members of My Bloody Valentine lost contact with each other while looking for accommodation and Tina Durkin, not confident in her abilities as a keyboard player, left the band.[10] When the remaining three members regained contact with one another, the band decided to audition bassists, as they lacked a regular bassist since their formation. Shields acquired Debbie Googe's telephone number from a contact in London, invited her to audition and subsequently recruited her as a bassist. Googe managed to attend rehearsals, which were centred around her day job. Rehearsal sessions were regularly held at Salem Studios, which was connected to the independent record label Fever Records. The label's management were impressed with the band and agreed to release an extended play, provided the band would finance the recording sessions themselves. Released in December 1985, Geek! failed to reach the band's expectations; however, soon after its release, My Bloody Valentine were performing on the London gig circuit, alongside bands such as Eight Living Lags, Kill Ugly Pop and The Stingrays.[10]

Due to the band's slow progress, Shields contemplated relocating to New York City, where members of his family were living at the time. However, Creation Records co-founder Joe Foster had decided to establish his own record label, Kaleidoscope Sound and persuaded My Bloody Valentine to record and release an EP. The New Record by My Bloody Valentine, produced by Foster, was released in October 1986 and was a minor success, peaking at number 22 on the UK Indie Chart upon its release.[15] On the strength of the release, the band began performing more frequent shows, later developing a small following and travelling outside London for live performances, supporting and opening for bands such as The Membranes.[10]

1987: Lazy Records and Butcher's recruitment

.jpg.webp)

In early 1987, My Bloody Valentine signed to Lazy Records, another independent record label, which was founded by the indie pop band The Primitives and their manager, Wayne Morris. My Bloody Valentine's first release on the label was the single "Sunny Sundae Smile", released in February 1987. It peaked at number 6 on the UK Indie Singles Chart[16] and the band toured following its release. After a number of performances throughout the United Kingdom, the band managed to secure a support slot with The Soup Dragons. In March 1987, during the tour with The Soup Dragons, David Conway announced his decision to leave the band, due to a gastric illness, disillusionment with music and ambitions to become a writer.[13]

Conway's departure left My Bloody Valentine without a lead vocalist—a situation Shields, Ó Cíosóig and Googe decided to amend by placing advertisements in the local music press. The audition process, which Shields described as "disastrous and excruciating", was unsuccessful due to Shields "mentioning The Smiths, because [he] liked their melodies", which attracted a number of vocalists he referred to as "fruitballs".[10] Although considering forming another group, the band were recommended a number of vocalists from peers and experimented with two lead vocalists, Bilinda Butcher and Joe Byfield. Byfield was deemed unsuited as a vocalist and the band recruited Butcher. Butcher, whose prior musical experience was playing classical guitar as a child and singing and playing tambourine "with some girlfriends for fun", had learned that My Bloody Valentine needed a backing vocalist from her partner, who had met Colm Ó Cíosóig on a ferry from the Netherlands. At her audition for the band, she sang "The Bargain Store", a song from Dolly Parton's 1975 album of the same name.[17]

In light of Butcher's recruitment, Shields became a co-lead vocalist, splitting and often sharing duties alongside Butcher. Commenting on the transition, Shields noted that Butcher "sounded all right and she could sing one of our songs, we just had to show her how to play guitar."[10] Shields was initially reluctant to take on a vocal role within the band, but said that he had "always sung in the rehearsal room [...] and made up the melodies." With the new line up in place, the band intended to drop the My Bloody Valentine moniker, but according to Ó Cíosóig and Shields, the band was unable to decide on a name and kept the moniker "for better or for worse".[18]

Under pressure from Lazy Records to release a full-length album, My Bloody Valentine compromised and agreed to release a single and subsequent mini album, citing the need for time to stabilize their new line-up. "Strawberry Wine", a three-track single, was released in November 1987 and Ecstasy was released a month later. Both received moderate critical acclaim, and peaked at number 13 and 12 on the independent singles and albums chart, respectively.[15] "Strawberry Wine", however, was described as "certainly the better of the two releases", as Ecstasy was plagued by production difficulties, including errors in the mastering process. Ecstasy was criticised as showing "a group who appeared to have run out of money halfway through recording",[10] which was later confirmed, as the band were funding the studio sessions themselves. My Bloody Valentine's contract with Lazy stated that the label would handle promotion of releases, whereas the band would finance the recording sessions. Following their departure from Lazy, who later rereleased "Strawberry Wine" and Ecstasy on the compilation album Ecstasy and Wine (1989) without the band's consent,[19] Rough Trade Records offered a deal to finance the recording and release of a full-length album, but the band turned it down.[10]

1988–1991: Creation Records and Loveless

In January 1988, My Bloody Valentine performed in Canterbury, opening for Biff Bang Pow!, a band that featured Creation Records founder Alan McGee. After "blowing [Biff Bang Pow!] off the stage", My Bloody Valentine were described as "the Irish equivalent to Hüsker Dü" by McGee,[20] who approached the band after the show and offered them an opportunity to record and release a single on Creation. The band recorded five songs at a studio in Walthamstow, East London in less than a week and in August 1988, released You Made Me Realise. The EP was well received by the independent music press and according to AllMusic's Nitsuh Abebe, the release that "made critics stand up and take notice of the brilliant things My Bloody Valentine were up to", adding "it developed some of the stunning guitar sounds that would become the band's trademark".[21] It debuted at number 2 on the UK Indie Chart.[22] Following the success of You Made Me Realise, My Bloody Valentine released their debut full-length studio album, Isn't Anything, in November 1988. Recorded in rural Wales,[23] the album was a major success, receiving widespread critical acclaim, peaking at number 1 on the UK Indie Chart[15] and influencing a number of "shoegazing" bands, who according to Allmusic, "worked off the template My Bloody Valentine established with [the album]".[24]

In February 1989, My Bloody Valentine began recording their second studio album at Blackwing Studios in Southwark, London. Creation Records believed that the album could be recorded "in five days". However, it soon "became clear that wasn't going to happen".[25] Following several unproductive months,[26] during which Shields assumed main duties on the musical and technical aspects of the sessions, the band relocated to a total of nineteen other studios and hired a number of engineers, including Alan Moulder, Anjali Dutt and Guy Fixsen. Due to the extensive recording time, Shields and Alan McGee agreed to release another EP[27] and subsequently the band released Glider in April 1990. Containing the lead single "Soon", which featured the first recorded use of Shields' "glide guitar" technique,[28] the EP peaked at number 2 on the UK Indie Chart[29] and the band toured in summer 1990 to support its release.[30] In February 1991, while still recording their second album, My Bloody Valentine released Tremolo, which was another critical success and topped the UK Indie Chart.[31]

Released in November 1991, Loveless was rumoured to have cost over £250,000 and bankrupted Creation Records, claims which Shields has denied.[32] Critical reception to Loveless was almost unanimous with praise[33] although the album was not a commercial success. It peaked at number 24 on the UK Albums Chart[34] but failed to chart elsewhere internationally. McGee dropped My Bloody Valentine from Creation Records soon after the release of Loveless, due to the album's extensive recording period and interpersonal problems with Shields.[35]

1992–1997: Island Records and breakup

My Bloody Valentine signed with Island Records in October 1992 for a reported £250,000 contract.[36] The band's advance went towards the construction of a home studio in Streatham, South London, which was completed in April 1993. Several technical problems with the studio sent the band into "semi-meltdown", according to Shields,[37] who was rumoured to have been suffering from writer's block.[17] The band remained largely inactive, but they recorded and released two cover songs from 1993 to 1996—a rendering of "We Have All the Time in the World" by Louis Armstrong for Peace Together[38] and a cover of "Map Ref. 41°N 93°W" by Wire for the tribute album Whore: Tribute to Wire.[39]

In 1995, Debbie Googe and Colm Ó Cíosóig left My Bloody Valentine. Googe, who briefly worked as a taxi driver following her departure, formed the indie rock supergroup Snowpony with Katharine Gifford, who also performed with Stereolab and Moonshake,[40] and Ó Cíosóig relocated to the United States, forming Hope Sandoval & the Warm Inventions with Hope Sandoval of Mazzy Star.[41] Shields and Butcher attempted to record a third studio album, which Shields claimed would be released in 1998.[42] Butcher departed the band in 1997.[17] Unable to finalise a third album, Shields isolated himself, and in his own words "went crazy", drawing comparisons in the music press to the eccentric behavior of Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys and Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd.[35] Shields later became a touring member of Primal Scream, collaborated with a number of artists including Yo La Tengo, Dinosaur Jr., and Le Volume Courbe[43] and recorded songs for the soundtrack to the 2003 film Lost in Translation.[44]

Rumours had spread amongst fans that albums worth of material had been recorded and shelved prior to the band's break up. In 1999, it was reported that Shields had delivered 60 hours of material to Island Records,[36] and Butcher confirmed that there existed "probably enough songs to fill two albums."[17] Shields later admitted that at least one full album of "half-finished" material was abandoned, stating "it was dead. It hadn't got that spirit, that life in it."[45]

2007–2013: Reunion and m b v

In August 2007, reports emerged suggesting My Bloody Valentine would reunite for the 2008 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in Indio, California, United States.[46] Similar reports had circulated in 2003, stating that Shields, Butcher and Ó Cíosóig were together in Berlin, Germany, re-recording five songs recorded for Glider, which were due for release on an upcoming box set;[47] and in 2007, reports suggested My Bloody Valentine were due to perform at a series of Pod-organised concerts at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Kilmainham, Dublin.[48] Shields later confirmed the reunion and said that the band's third studio album, which he had begun recording in 1996, was near completion.[49] Three live shows in the United Kingdom were announced in November 2007[50] and on 13 June 2008, My Bloody Valentine performed in public for the first time in 16 years during two live rehearsals at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.[51]

.jpg.webp)

My Bloody Valentine began an extensive worldwide tour throughout summer and autumn 2008. The band began performing at European music festivals, including the Roskilde Festival in Roskilde, Denmark,[52] Øyafestivalen in Oslo, Norway,[53] and Electric Picnic in Stradbally, Ireland,[54] as well as the Fuji Rock Festival in Niigata, Japan.[55] From 19 to 21 September, the band curated and performed at the 2008 All Tomorrow's Parties festival in New York, United States and later performed throughout North America, including dates in Chicago, Toronto, Denver, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Austin.[56] The band spent £200,000 on equipment for their world tour,[57] which was their first since 1992 in support of Loveless.[58]

Following additional touring in 2009, as loudest live music in the Globe, My Bloody Valentine dedicated their time to completing their third album. Rumours of a My Bloody Valentine box set, which had circulated amongst the public in April 2008 following a listing on HMV Japan's web site,[59] began recirculating. In March 2012, after a number of reported delays, Sony Music Ireland announced the release of the compilation album EP's 1988–1991—a collection of the band's Creation Records extended plays, singles and unreleased tracks.[60] The compilation album was released on 4 May 2012, alongside remastered versions of Isn't Anything and Loveless.[61]

In November 2012, Kevin Shields announced plans to release My Bloody Valentine's third album online before the end of the year.[62] In December, the band announced on Facebook that the album was completed and mastered,[63] and on 27 January 2013, during a warm-up show at Electric Brixton in London, Shields told the audience that the album "might be out in two or three days."[64] The album, titled m b v, was released through the band's official website on 2 February 2013, although the site crashed on its launch due to high traffic.[65] Upon its release, m b v received "universal acclaim", according to Metacritic,[66] and the band began a worldwide tour.[67]

2013–present: Future plans

In 2013, Shields announced plans to release a My Bloody Valentine EP "of all-new material", which would be followed by a fourth studio album.[68] In September 2017, it was reported that Shields was working on material for a new My Bloody Valentine album that was projected for release in 2018.[69] As of 2018, two EPs were expected to be released in 2019, but all previously-announced release estimates have not been met.[70]

In April 2020, American clothing brand Supreme announced a collaboration with My Bloody Valentine, licensing the album art of Glider, Feed Me With Your Kiss and Loveless for the company's Spring 2020 clothing collection.[71][72]

Style

Influences

My Bloody Valentine's musical style progressed throughout their career. The band were originally influenced by post-punk acts such as The Birthday Party, The Cramps and Joy Division, and according to author Mike McGonial "brought together the least interesting elements" of their influences.[4] Their debut mini album, This is Your Bloody Valentine (1985), incorporated a further gothic rock sound which AllMusic referred to as "unfocused and derivative".[73] However, when the band began experimenting with pop melodies on The New Record by My Bloody Valentine (1986), it marked "a vital point in the development of their sound",[74] which was influenced primarily by The Jesus and Mary Chain. The band later took a "rarified, effete and poppy approach to Byrdsian rock" with their two successive releases, "Strawberry Wine" and Ecstasy (1987).[75] Isn't Anything and its preceding releases were influenced by American indie rock bands, most notably the distorted guitar-based music of Dinosaur Jr. and Sonic Youth, and saw Shields develop his trademark guitar techniques.[76]

The band were also influenced by house music as well as hip hop; of the latter, Shields said "it beats the shit out of most rock music when it comes to being experimental, it's been a constant source of inspiration to us."[77] Shield's experimentation with guitar tone would be influenced by sampled sounds employed by Public Enemy and the Bomb Squad,[78] which Shields described as "half-buried or muted, a real sense of sounds being semi-decayed, or destroyed, but then re-used."[79] The band began experimenting with samplers around the time of the Glider EP, utilizing them to play back and manipulate their own guitar feedback and vocals on keyboards; by the time of the Tremolo EP, they had acquired a professional Akai sampler.[79] In the mid-1990s, during the recording of m b v (2013), Kevin Shields and Colm Ó Cíosóig began experimenting with jungle and drum and bass music, an underground dance scene in London at the time.[80][81]

Sound

One of the most recognisable aspects of My Bloody Valentine's music is Shields' guitar sound, which "use[s] texture more than technique to create vivid soundscapes."[28] During the late 1980s, Shields began customising the tremolo systems for his Fender Jaguars and Jazzmasters; extending the tremolo arm and loosening it considerably, to allow him to manipulate the arm while strumming chords,[28] which resulted in excessive pitch bending. Shields used a number of alternate and open tunings[11] that together with his tremolo manipulation achieved "a strange warping effect that makes the music wander in and out of focus", according to Rolling Stone.[82] Shields' most notable effect is reverse digital reverb, sourced from a Yamaha SPX90 effects unit. Together with the tremolo manipulation and distortion, he created a technique known as "glide guitar".[83] Shields effects rig, which is composed largely of distortion, graphic equalizers and tone controls,[84] consists of at least 30 effects pedals[57] and is connected to a large number of amplifiers, which are often set to maximum volume to increase sustain. During live performances, and in particular the closing song "You Made Me Realise", My Bloody Valentine perform an interlude of noise and excessive feedback, known as "the holocaust", which would last for half an hour and often reached 130db.[85] Shields later remarked "it was so loud it was like sensory deprivation. We just liked the fact that we could see a change in the audience at a certain point."[35]

Bilinda Butcher's vocals have been referred to as a trademark of My Bloody Valentine's sound, alongside Shields' guitar techniques. On a number of occasions during the recording of Isn't Anything and Loveless, Butcher was awoken and recorded vocals, which she said "influenced [her] sound" by making them "more dreamy and sleepy".[86] The vocals in most My Bloody Valentine's recordings are low in the mix[87] as Shields intended for the vocals to be used as an instrument.[88] Critics have often described an androgynous sound to the band's vocals.[89] My Bloody Valentine's lyrics are mostly written by Shields. However, Butcher wrote a third of the lyrics on both Isn't Anything and Loveless, but has referred to a lot of the lyrics as "plain nonsense." According to Butcher, she "didn't have a plan and never thought about lyrics until it was time to write them. I just used whatever was in my head for the moment."[17] Some of her lyrics were written as a result of attempting to interpret rough versions of songs Shields had recorded. Butcher has said: "He [Shields] never sang any words on the cassettes I got but I tried to make his sounds into words."[17] Butcher and Shields would often spend eight to ten hours a night writing lyrics, even though few changes actually resulted, as Shields believed "there's nothing worse than bad lyrics."[90] Spin writer Simon Reynolds has noted that the band's lyrics often contain sexual themes, which are "a paradoxical blend of force and tenderness".[89]

Legacy

My Bloody Valentine are regarded by some as the pioneers of the alternative rock subgenre known as shoegazing,[24] a term coined by Sounds journalists in the 1990 to describe certain bands' "motionless performing style, where they stood on stage and stared at the floor".[91][92] The band's releases on Creation Records influenced shoegazing acts, including Slowdive, Ride and Lush, and are regarded as providing a platform to allow the bands to become recognised.[93] Following the release of Loveless (1991), My Bloody Valentine were "poised for a popular breakthrough", although never achieved mainstream success. However, the band are noted to have been "profoundly influential in the direction of '90s alternative rock", according to AllMusic.[94] In 2017, a study of AllMusic's database indicated My Bloody Valentine as its 26th most frequently cited influence on other artists.[95]

Several alternative rock bands have cited My Bloody Valentine as an influence. The Smashing Pumpkins frontman Billy Corgan was influenced by Isn't Anything upon its release and attempted to recreate its sound on the band's debut album Gish (1991), particularly the closing track "Daydream" which Corgan described as "a complete rip-off of the My Bloody Valentine sound."[96] The Smashing Pumpkins two successive studio albums, Siamese Dream (1993) and Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness (1995), were also influenced by the band.[96] Courtney Love cited the band as an influence on Hole's third album Celebrity Skin (1998).[97]

Isn't Anything was included in The Guardian's list of "1000 Albums to Hear Before You Die"[98] and listed at number 22 on Pitchfork's "Top 100 Albums of the 1980s."[99] Loveless was named the best album of the 1990s by Pitchfork in 1999[100] and in 2003, the album was listed as number 219 on Rolling Stone's list of "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time."[101] In 2008, both albums were featured on The Irish Times' "Top 40 Irish Albums of All Time" list, where Isn't Anything ranked at number 27 and Loveless at number 1.[102] In 2013, Loveless placed third in the Irish Independent's "Top 30 Irish Albums of All Time" list.[103]

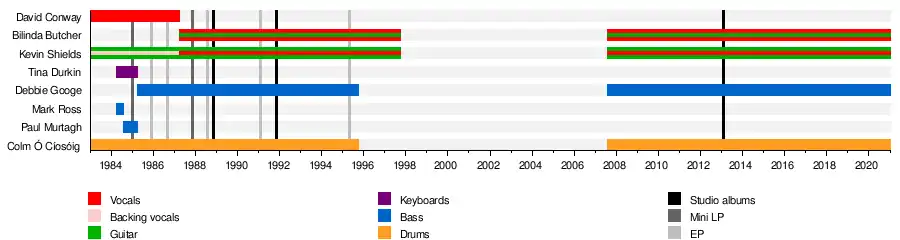

Members

Current

Touring musicians

|

Former

|

Timeline

Discography

- Isn't Anything (1988)

- Loveless (1991)

- m b v (2013)

See also

References

Citations

- Sutherland, Mark (13 March 2013). "My Bloody Valentine Bring the Noise in London". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- Reynolds, Simon (1 December 1991), "Pop View; 'Dream-Pop' Bands Define the Times in Britain", The New York Times, The New York Times Company, retrieved 7 March 2010

- Goddard, Michael, with Benjamin Halligan and Nicola Spellman (2013). Resonances: Noise and Contemporary Music. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-1441159373.

The more contemporary Anglo-Irish experimental rock band My Bloody Valentine were notorious for employing loud volumes in live performances; their reunion concerts in 2008 and 2009 were noteworthy for the controversy around the extreme loudness, with earplugs on offer at the doors and some audience members leaving because they felt 'physically distressed' by the noise.

- McGonial 2007, p. 21.

- North, Aaron; Kevin Shields (19 January 2005). "Kevin Shields: The Buddyhead Interview" (PDF). Buddyhead (Interview). New York. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Britton 2011, p. 134.

- Murphy, Peter (2004). "Lost in Transmution: Kevin Shields". Hot Press. Osnovina (May 2004).

- "Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine: Interview on AOL". AOL. 7 February 1997. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- Walsh, Aidan (2000). Aidan Walsh: Master of the Universe (DVD). Dublin: Zanzibar Films. Event occurs at .

- Brown, Nick (February 1991). "My Bloody Valentine". Spiral Scratch.

- Shields, Kevin (2000). The Lost Albums: Loveless (TV). Dublin: @lastTV. Event occurs at 00:51–04:47.

- Stubbs, David (26 January 1991). "My Bloody Valentine: All Hail the Future!". Melody Maker.

- Booth, Vachel (1989). "My Bloody Valentine: Weep For You". Underground (February 1989): 25.

- McGonial 2007, p. 23.

- Lazell 1997, p. 155.

- Lazell 1997, p. 157.

- Johannesson, Ika (3 September 2008). "TD Archive: My Bloody Valentine's Bilinda Butcher Interviewed". Totally Dublin. Totally Partner. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Ó Cíosóig, Colm; Shields, Kevin (1988). "Transmission" (Interview). Interviewed by Rachael Davis. Channel 4.

- "My Bloody Valentine". Whoosh (3). 1989.

- McGonial 2007, p. 26–27.

- Abebe, Nitsuh. "You Made Me Realise [Creation] – My Bloody Valentine: Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Lazell 2007, p. 155.

- Blashill, Paul (1989). "My Waking Dream". Spin. Spin Media (May 1989): 12. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- "Shoegaze: Significant Albums, Artists and Songs". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- McGonial 2007, p. 41.

- McGonial 2007, p. 43.

- McGonial 2007, p. 44.

- DiPerna 1992, p. 26.

- "Indie Charts: 19 May 1990". The ITV Chart Show. 19 May 1990. ITV.

- McGonial 2007, p. 47.

- "Indie Charts: 2 March 1991". The ITV Chart Show. 2 March 1991. ITV.

- McGonial 2007, p. 66–67.

- McGonial 2007, p. 97.

- "My Bloody Valentine | Artist". Official Charts Company. British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Lester, Paul (12 March 2004). "Kevin Shields: I Lost It | Music". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- Stubbs, David (1999). "Sweetheart Attack: My Bloody Valentine's Isn't Anything is The Eighties Rock Album". Uncut. IPC Media (February 1999).

- McGonial 2007, p. 101-102.

- "Peace Together – Various Artists: Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- "Whore: Tribute to Wire – Various Artists: Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- "Interviews: My Bloody Valentine". Creation Records. August 2001. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- Rondeau, Bernardo (29 January 2003). "My Bloody Valentine: Loveless". PopMatters. PopMatters Media. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- Shields, Kevin (July 1997). "About Bloody Time Too!". NME. IPC Media.

- "Kevin Shields – Credits". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "From My Bloody Valentine to Lost in Translation". NPR. 15 September 2003. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- "My Bloody Valentine interview". KUCI. University of California. Archived from the original on 12 September 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- Cohen, Jonathan (27 August 2007). "Report: My Bloody Valentine Mulling Coachella Reunion". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "My Bloody Valentine back in the studio". Hot Press. Osnovina. 17 July 2003. Retrieved 28 June 2013. (subscription required)

- "My Bloody Dublin Reunion?". Phantom 105.2. 17 July 2007. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Cohen, Jonathan (7 November 2007). "Shields Confirms My Bloody Valentine Reunion". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

- Smith, Caspar Llewellyn (15 November 2007). "Slow news day: My Bloody Valentine will gig". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Denney, Alex (16 June 2008). "Review / My Bloody Valentine @ ICA, London, 13/06/08 / Gigs". Drowned in Sound. Silentway. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Madsen, Finn P. (6 July 2008). "My Bloody Valentine: Roskilde Festival, Arena – Anmeldelse" [My Bloody Valentine: Roskilde Festival, Arena – Review]. Gaffa (in Danish). Gaffa A/S. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "Shoegazer-comeback på Øya" [Shoegazer-Comeback on the Island] (in Norwegian). NRK. 31 January 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Carroll, Jim (13 February 2008). "My Bloody Valentine playing Electric Picnic | On the Record". The Irish Times. Irish Times Trust. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "Fuji Rock: History – 2008". Fuji Rock Festival. Smash Corporation. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Solarski, Matthew (6 May 2008). "My Bloody Valentine Announce North American Tour | News". Pitchfork. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Pareles, Jon (22 September 2008). "Music – My Bloody Valentine: Reunited, Rediscovers the Love – Review". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- "My Bloody Valentine to play first shows in 16 years | News". NME. IPC Media. 15 November 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- Thiessen, Brock (16 April 2008). "My Bloody Valentine Box Set For Sale Through HMV Japan • News". Exclaim!. 1059434 Ontario. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "My Bloody Valentine: New Releases – Friday 4th May". Sony Music Ireland. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "My Bloody Valentine to release new compilation album 'EP's 1988-1991' | News". NME. IPC Media. 22 March 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "My Bloody Valentine announce Loveless follow-up and Tokyo Rocks appearance". NME. IPC Media. 7 November 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- Pelly, Jenn; Phillips, Amy (24 December 2012). "My Bloody Valentine Finish Mastering New Album". Pitchfork. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Nelson, Michael (27 January 2013). "My Bloody Valentine New Album Could Be Released In "Two Or Three Days"; Hear New MBV Song". Stereogum. Spin Media. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "My Bloody Valentine's website crashes after midnight launch of new album". NME. IPC Media. 2 February 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "M B V Reviews, Ratings, Credits and More". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "My Bloody Valentine add dates to world tour". Fact. Vinyl Factory Group. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- Dombal, Ryan (9 August 2013). "Interviews: Kevin Shields | Features". Pitchfork. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- Geslani, Michellle (18 September 2017). "My Bloody Valentine may release new album in 2018". Consequence of Sound. consequenceofsound.net. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- Schatz, Lake (11 October 2018). "Kevin Shields says My Bloody Valentine will release two new albums, debuts Brian Eno collaboration “The Weight of History”: Stream". Consequence of Sound. consequenceofsound.net. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Monroe, Jazz. "My Bloody Valentine and Supreme Launch Clothing Collection". Pitchfork. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "Supreme x My Bloody Valentine Spring 2020 Collection". HYPEBEAST. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "This is Your Bloody Valentine – My Bloody Valentine: Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Abebe, Nitsuh. "The New Record by My Bloody Valentine – My Bloody Valentine: Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- McGonial 2007, p. 24.

- McGonial 2007, p. 54.

- Dalton, Stepheb. "My Bloody Valentine: 'It's just pure noise for the hell of it' – a classic interview from the vaults". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- McLeod, Kembrew; Peter DiCola (2011). Creative License: The Law and Culture of Digital Sampling. Duke University Publishers. p. 193.

- Parkes, Taylor. ""Not Doing Things Is Soul Destroying" - Kevin Shields of MBV Interviewed". The Quietus. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- McGonial 2007, p. 102.

- Richardson, Mark (6 February 2013). "My Bloody Valentine: mbv | Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Azerrad, Michael (1992). "The Sound of the Future: My Bloody Valentine". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media (6 February 1992).

- DiPerna, p. 152.

- Double, Steve (1992). "Kevin Shields, My Bloody Valentine Interview". NME. IPC Media (9 November 1992): 14.

- Ewing, Tom (23 June 2008). "Articles: My Bloody Valentine | Features". Pitchfork. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- DeRogatis, Jim (2 December 2001). "A Love Letter to Guitar-Based Rock Music". Chicago Sun-Times. Sun-Times Media Group. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- McGonial 2007, p. 75.

- McGonial 2007, p. 76.

- Reynolds, Simon. "The Opposite of Rock 'N Roll". Spin. Spin Media (August 2008): 78–80.

- McGonial 2007, p. 78–79.

- McGonial 2007, p. 31.

- Larkin, Colin (1992). The Guinness Who's Who of Indie and New Wave Music. Guinness World Records. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-8511-2579-4.

- Strong, Martin C. (1999). The Great Alternative & Indie Discography. Canongate. p. 427. ISBN 0-86241-913-1.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "My Bloody Valentine – Music Biography, Credits and Discography". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- Kopf, Dan; Wong, Amy X. (7 October 2017). "A definitive list of the musicians who influenced our lives most". Quartz.

- Corgan, Billy (2011). Smashing Pumpkins Webisode #1 – Daydream (Online). Event occurs at 00:16–02:12.

- Love, Courtney (1998). "Celebrity Skin: The Interview; CD" (Interview).

- "Series: 1000 Albums to Hear Before You Die – Artists beginning with M (Part 3)". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. 21 November 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "Staff Lists: Top 100 Albums of the 1980s | Features". Pitchfork. 20 November 2002. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- DiCrescenzo, Brent. "Top 100 Albums of the 1990s: Loveless". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 14 September 2005. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "219) Loveless". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media. 1 November 2003. Archived from the original on 6 January 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "The Top 40 Irish Albums". The Irish Times. Irish Times Trust. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 28 June 2013. (subscription required)

- Meagher, John (19 April 2013). "Day & Night: The Top 30 Irish Albums of All Time". Irish Independent. Independent News & Media. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

Bibliography

- Belhomme, Guillaume (2016). My Bloody Valentine / Loveless. Discogonie. France: Editions Densité. ISBN 978-2-9192-9605-7.

- McGonial, Mike (2007). Loveless. 33⅓. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1548-6.

- Britton, Amy (2011). Revolution Rock: The Albums Which Defined Two Ages. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4678-8710-6.

- DiPerna, Alan (1992). "Bloody Guy". Guitar World. Harris Publications (March 1992).

- Lazell, Barry (1997). Indie Hits: 1980–1989: The Complete Guide to UK Independent Charts (Singles & Albums). London: Cherry Red. ISBN 0-9517206-9-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to My Bloody Valentine (band). |