Natal Mounted Police

The Natal Mounted Police (NMP) were the colonial police force of the Colony of Natal created in 1874 by Major John Dartnell, a farmer and retired officer in the British Army as a semi-military force to bolster the defences of Natal in South Africa. When required the NMP would be assisted by the Colony’s volunteer regiments including the Natal Carbineers. It enlisted European officers, NCOs and natives and men of the NMP fought and died in the Battle of Isandlwana and at Rorke's Drift during the Zulu War of 1879.

Natal Mounted Police 1873-1894

The Natal legislature established the Natal Mounted Police in 1874 following an rebellion by Chief Langalibalele.[1] However, the Natal legislature were slow to appropriate funds for the organization.[2] The first commandant was Major John George Dartnell (1838-1913) formerly of the 86th (Royal County Down) Regiment of Foot while the first enrolled trooper was Edward Babington of Londonderry in 1874.[3] Dartnell later described his recruits as the:

...flotsam and jetsam of the colony, and a very rough lot they proved to be, being principally old soldiers and sailors, transport riders, and social failures from home, etc. They were, however, a very fine, hardy lot of men, ready to go anywhere and do anything, and very willing and cheerful if a little troublesome in town; but in the country, away from temptation, they were excellent men who grumbled occasionally, of course, but were more inclined to laugh at and make like of discomfort and hardship.

In its early days the Natal Mounted Police mustered 50 whites and 150 Africans;[4] it was seriously under-manned and poorly equipped yet nevertheless managed to gain an enviable reputation for camaraderie and efficient policing. The first headquarters were at Fort Napier in Pietermaritzburg.[5] In 1877 twenty-five men of the Natal Mounted Police provided the protective escort for Sir Theophilus Shepstone, the Special Commissioner, when he went to Pretoria to issue a proclamation announcing the establishment of British authority over the Transvaal. No overt opposition was made to the annexation

Zulu War

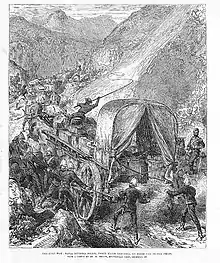

The Natal Mounted Police saw little action until the Zulu War of 1879 when it was attached to the British Army as part of the Colonial mounted force and entered into the Zulu Kingdom with the Central Column under the command of Lord Chelmsford. One detachment of 97 men of the NMP led by Major Dartnell was sent to find the location of the Zulu army of Cetshwayo kaMpande while the second detachment of 34 men fought in the Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879. Of this second detachment 25 were killed in the battle with 21 killed fighting alongside 19 Natal Carbineers in a 'last stand' defending Lieutenant-Colonel Anthony Durnford. Three men of the NMP escaped from Isandlwana and made their way to Rorke's Drift where they fought in the Battle of Rorke's Drift, where one of them, Sidney Hunter, was killed in action.[6][7] The first detachment of the NMP under Dartnell returned to Isandlwana on the evening of the battle where they spent the night among the ruins of the camp and the bodies of their colleagues before accompanying Lord Chelmsford's relief column on its advance to Rorke’s Drift early the next morning. When Sir Garnet Wolseley arrived in Durban in July 1879 to supersede Lord Chelmsford as commander of the forces in the Zulu War and as Governor of Natal and the Transvaal and the High Commissioner of Southern Africa the Natal Mounted Police provided his escort during his visit to Zululand in the final days of the War.

Rebellions

Natal Mounted Policemen later served in the Basuto Gun War (1880-81), where they defended the passes of the Drakensberg against attack from the Basuto, and the Transvaal Rebellion (also known as the First Anglo-Boer War) (1880-81) when the NMP was used to form a mounted military force on the border with the Transvaal. When after these Rebellions normal policing duties were resumed men of the NMP provided an escort for the Empress Eugénie in 1880 when she came to Natal to see where her son, Napoléon the Prince Imperial, had been killed the previous year during the Zulu War. The only campaign medals ever awarded to men of the Natal Mounted Police were earned during this period. These were 257 awards of the South Africa Medal (1877-79) for service during the Zulu War and the Cape of Good Hope General Service Medal for service during the Basutoland Rebellion. After 1881 police out-stations were set up across Natal with policing often consisting of long patrols in remote locations.[8] By 1885 the roll-call of the NMP was 300 white officers and 25 Africans.[3]

Natal Police 1894-1913

In 1894 the Natal Mounted Police was merged with the Colony of Natal's various police and prison services to create the Natal Police (NP), the name it was known by until it was disbanded in 1913.[8] Commandant John Dartnell was appointed the first Chief Commissioner of Police of the new force.

Innovations in policing

The Natal Police were the first to introduce finger-printing in Africa for use in forensic identification. The scheme was launched by Sub-Inspector W. J. Clarke of the Natal Police's Criminal Investigation Department (CID) who was impressed by the effective use of finger-printing for solving crime in Calcutta in 1897 and who tried to introduce the system in Natal in 1898. His superiors in the Natal Police did not share his enthusiasm for this new forensic innovation so Clarke launched the system at his own expense. Once it had proved its worth by leading to more arrests and crime-solving finger-printing became part of normal police procedure in Natal. So effective was the system that by 1910 the Natal Police's CID had more sets of finger-prints in its records than Scotland Yard had in its.[8] Clarke was to succeed Dartnell as Chief Commissioner on his retirement in 1903

Boer War 1899-1902

When in September 1899 war with the Boer Republic looked likely the men of the Natal Police were put on alert and used to watch the borders. When war was eventually declared in October 1899 the first casualties were a Natal Police picket at De Jager's Drift who were captured by the Boers. Consequently all the men of the Natal Police in northern Natal were sent to Dundee where they fought in the Battle of Talana Hill on 20 October 1899. The British forces including 90 men of the Natal Police under the command of Colonel Dartnell then retired to Ladysmith where they became besieged during the Siege of Ladysmith. The Natal Police came under fire at Lombard's Kop on 30 October 1899. At Ladysmith the Natal Police had one man killed and three wounded while a further three died of disease.[8]

On 7 December 1899 during the Siege the Natal Volunteers and the Imperial Light Horse launched a night attack from Ladysmith on Gun Hill with the Natal Police guarding the left flank during the action. The Imperial Light Horse and Natal Carbineers with a team from the Royal Engineers caught the Boers off-guard and forced them to withdraw and abandon their guns. The Royal Engineers placed explosives on a howitzer artillery piece and a Long Tom, taking the breechblock from the Long Tom and removing a Maxim gun back to Ladysmith. Being on the other side of a hill the Natal Police did not hear the bugle call "retire" and were late returning to Ladysmith. The NP saw further action during the evening of 5 January 1900 when a picket near Caesar's Camp (named after Caesar's Camp, an ancient feature near Aldershot which it resembled) were fired on during a major assault by the Boers on the British at Wagon Hill. Early next morning the Boers shot the horses of the NP forcing them to make their own way back by foot at the same time enduring withering rifle fire. After a British counterattack the Boers withdrew. The Siege of Ladysmith ended on 28 February 1900 when an advance party of the Composite Regiment of the Mounted Brigade reached Ladysmith which including 15 members of the Natal Police.[8]

Those men of the Natal Police who were not at Ladysmith when it was besieged were excused police duties and instead served in a military role with the Natal Police Field Force (NPFF). One section was the bodyguard for General Sir Redvers Buller VC when he was appointed to the Command of the British forces in Natal.

Dartnell retired in 1903 as Major-General Sir John Dartnell, KCB, CB

Later service

The 1,100 men of the Natal Police saw action during the 1906 Natal Rebellion which broke out in Natal during a Zulu revolt against British rule and taxation. Following the unification of South Africa in 1910 the Colonial police forces were wound down with the Natal Police ceasing to exist in 1913. Its police officers were reassigned to military units including the 2nd and 3rd Regiments of the South African Mounted Riflemen[3] or into the South African Police or the South African Prisons Service.[8][9]

References

- Colonel W. T. Clarke, 'Natal Mounted Police' - The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles, 1 July 1931

- Holt, H. P. (1913). The Mounted Police of Natal. London: J. Murray. p. 15. OCLC 458059621.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Natal Mounted Police and Natal Police /Nominal roll - The Campbell Collections of the University of KwaZulu-Natal

- Holt 1913, p. 15

- Holt 1913, p. 19

- Kenneth Darwin (ed), Familia 1991: Ulster Geneological Review, Number 7- Google Books p. 44

- UK, Military Campaign Medal and Award Rolls, 1793-1949: Africa, South Africa 1877-1879, Colonial Corps - Ancestry.com (subscription required)

- Natal Mounted Police - Anglo-Boer War database

- McCracken, Donal P. 'The Irish in South Africa - The Police, A Case Study' [Part 2], Familia, Journal of the Ulster Historical Foundation (volume 2, no. 7, 1991)