National Internment Camp for Women in Hovedøya

The National Internment Camp for Women in Hovedøya (Norwegian: Statens interneringsleir for kvinner, Hovedøya) was Norway's largest internment camp for women, located on the island of Hovedøya in Oslo.[1] It was used to detain women who had been accused of having romantic or sexual liaisons with German soldiers during World War II.[2]

| National Internment Camp for Women in Hovedøya | |

|---|---|

| Internment camp | |

Aerial photo of Hovedøya today. The camp was located in the clearing at the narrowest part of the island. | |

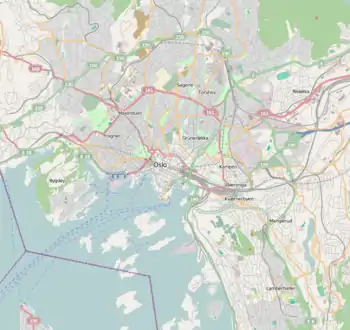

Location of Hovedøya within Oslo  National Internment Camp for Women in Hovedøya (Norway) | |

| Coordinates | 59°53′41.15″N 10°43′45.1″E |

| Other names | Statens interneringsleir for kvinner, Hovedøya |

| Location | Hovedøya in Oslo, Norway |

| Built by | Kongens Garde, Nazi Germany |

| Operated by | Government of Norway |

| Original use | Recruit training camp for Hans Majestet Kongens Garde |

| Operational | 1 Oct 1945 – May 1946 |

| Inmates | Tyskertøser |

| Number of inmates | 1,100 |

Construction

The oldest buildings that were used as part of the camp on Hovedøya were built in 1914 as recruit training grounds for Hans Majestet Kongens Garde. The Kongens Garde held training exercises on the island for six weeks every summer, from 1 April to 15 October, every year until 1939. However, most of the buildings were built by the Germans when they took over the island in 1940 to house Wehrmacht soldiers. The facility, renamed Lager Hovedöen, was expanded by 11 barracks with room for over 1,000 soldiers, a stockpile of explosives, and a field hospital with 100 beds.[2] By the end of the war, the camp was abandoned until its use as an internment camp for women a few months later. After the internment camp closed, the barracks were used as housing for 150 families up until the late 1950s. Today, the only part of the camp that remains is a single barracks building near the ruins of Hovedøya Abbey.

Background

Attitude towards "tyskertøser"

During the German occupation of Norway, the illegal press was very critical of women involved with German soldiers, since it was seen as fraternization with the enemy and a threat to the Norwegian resistance movement. In one of his radio broadcasts from London, Toralv Øksnevad warned, "The women who don't reject the Germans will pay a terrible price the rest of their lives."[3] However, even after the war the attitudes towards these women, commonly referred to as tyskertøser (English: German sluts), were overwhelmingly negative. An op-ed from Aftenposten in June 1945 read, "To cut off the hair of a German whore is too mild a punishment. They should be hated and tormented in every way, both male and female traitors."[4] The newspaper Nordlys suggested that the women be made to wear armbands marked with a "T" for tyskertøs. Out on the streets gangs of men, many of whom were former resistance fighters, would assault tyskertøser, shaving their heads or tearing their clothes off and painting them with a swastika.[4]

It was decided that these women should be separated from the rest of the population. A few official reasons were given, including to protect the women from being assaulted and to both give them treatment for and protect Norwegian men from any sexually transmitted diseases that they might have. The first camp used to hold these women in the Oslo area was a disused German labor camp for political prisoners on Ljanskollen, west of Holmlia, that was repurposed to hold tyskertøser on June 14, 1945. However, the camp was very small, holding only 250 prisoners, and was deemed unfit for winter use, so it was decided that a new camp should be set up.[5]

Purpose and legal basis

The official stance of the Norwegian government was that the internment camps were intended to protect the women from lynchings and prevent sexually transmitted diseases from spreading to Norwegian men, but the camp was also used to detain women who had lived "scandalous lives" or "went against the general consensus" about the German occupiers, as authorities explained in a 1945 interview with VG.[1] During the war, the Germans had kept a register of women with STDs, including information on which of these women had had intercourse with German soldiers. When the war ended the Ministry of Health and Care Services took over the list and expanded it, adding any woman who had been accused of being a tyskertøs or detained at Hovedøya. So while official figures stated that 75% of the camp's prisoners were infected with syphilis or gonorrhea, the actual figures were between 20 and 30%.[6]

Most of the women detained in Hovedøya had not broken Norwegian law, since sexual relations with German soldiers was not considered treason, and as such they had not seen trial. However, to legally justify keeping them detained, laws were cited that were either created during the war by Nasjonal Samling or provisional laws intended to be used against Nazi soldiers or collaborators. The main provisional law used to justify the camp was a law created in June 1945 authorizing preventative measures against STDs[7] and one from 1943 that gave the police authority to detain people without trial.[8] To justify forced unpaid labor in the camp, the camp management cited a law created under the Nasjonal Samling government that allowed putting "immoral" women to work, despite the fact that all laws enacted during wartime were immediately repealed after the occupation ended.

The camp at Hovedøya was for the most part unchallenged by the media. Aftenposten described the detainees as "the greatest danger to society," and Hovedøya was known colloquially as "de fortapte pikers øy" (English: the doomed girls' island).[1]

Operation

On 1 October 1945, the Hovedøya facility began operation under the leadership of psychologist Adolf Hals. There were a total of 1,100 women detained at the Hovedøya camp, most of them Oslo residents in their 20s, along with at least 16 children, who were cared for by their mothers as no other family members would take care of them. The women were interned for as long as was deemed necessary by the police or health authority who sent them there—though the average sentence was two months, the women could be held there from anywhere between a few days to over six months.[9] Some women who were considered particularly treasonous were transferred to Bredtveit Prison in northern Oslo.

Since the women were never formally detained, their doors were left unlocked and their windows unbarred. However, many aspects of the facility's design indicated its true purpose as a prison camp. The camp was surrounded by tall barbed wire fences and searchlights at night to enforce the strict 9:00pm curfew. The camp was also patrolled by armed guards who were authorized to open fire if necessary, but no incidences of this occurred. Incoming mail to the inmates was often censored or withheld entirely. During the day, the women were also put to work around the camp, given menial tasks such as raking leaves, gardening, sewing, or laying rat poison.[1] Any proceeds from their labor went directly to the camp.

Similar camps

The camp at Hovedøya was the largest of its kind with inmates from all over the country. However, there were many similar camps across Norway. The other main tyskertøs camp for the Oslo area was Hovelåsen outside Kongsvinger, which held 450 detainees. There were also small camps near most major Norwegian cities, such as in Tennebekk near Bergen, Selbu near Trondheim, Klekken near Hønefoss, and Skadberg near Stavanger.[1]

Closure

In April 1946, the camp was visited by Minister of Social Affairs Sven Oftedal. During the war Oftedal had been imprisoned in Grini and Sachsenhausen concentration camps for his role in the Norwegian resistance movement. When he saw the treatment of women in the camp, the resemblance to the German camps was too strong, and he ordered it to be immediately shut down. The barracks were completely cleaned out and the women sent back to Oslo by the following month.[10]

Aftermath

When the women landed at Vippetangen in Oslo, they were forced to sign statements that they would not be seen in public with uniformed men or foreigners.[1] But this was not the end of the punishment for some of these women, as about 3,500 Norwegian women who had married German soldiers were later deported to Germany.[11] The Norwegian nationality law of 1924 allowed Norwegians to be married to foreigners and retain their citizenship, as long as they were living in Norway. However, a provisional law that was passed by Stortinget in 1946 that made an exception for women married to German soldiers. In a statement for Odelsting proposition no. 136, government minister Jens Christian Hauge said of the women:

Most of these married women in their dealings with the occupying forces' soldiers and officers have behaved in a most undignified manner. Since they married Germans, their political ties to Norway should be broken. And it is highly desirable that they leave our country as soon as possible.

— Jens Christian Hauge, Ot.prp. 136[11]

Aside from a brief period between 1950 and 1955, these women were not allowed to reapply for citizenship for almost 45 years, when the deportation was reevaluated by Stortinget in 1989. In 2003, the Norwegian government finally apologized for the mistreatment of tyskertøser after the war. Though the camp at Hovedøya represented a dark chapter of Norway's history, at the time its prisoners provided a useful scapegoat for Norwegians who had suffered through a harsh German occupation. Terje A. Pedersen, a historian who focuses on the treatment of tyskertøser, wrote in his thesis: "Admitting that these relationships could be merely love affairs between normal people would disrupt the black and white image of the Germans and the war. It would have normalized the relationship to Germany in a way that was completely unacceptable after the war."[3]

External links

- Filmavisen news clip about the camp (in Norwegian)

References

- Eriksen, Frøydis (2010). Turguide til øyene i indre Oslofjord (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo kommune Friluftsetaten. p. 12. Retrieved 26 Jan 2013.

- "Fra Gardeleir til tysk militærleir". Natur og kultur på Hovedøya (in Norwegian). Norsk Institutt for Kulturminneforskning. Retrieved 28 Jan 2013.

- Førde, Kristin Engh (24 Sep 2007). "Simply in Love". Information Centre for Gender Research in Norway. Retrieved 28 Jan 2013.

- Aarnes, Helle (16 Mar 2008). "De brøt ingen lov". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 28 Jan 2013.

- "Ljanskollen". Oslo byleksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Selskabet for Oslo Byes Vel & Kunnskapsforlaget. 2010. p. 339.

- Drolshagen, Ebba D. De gikk ikke fri. p. 163. ISBN 9788249505920.

- Provisorisk anordning av 12. juni 1945 om åtgjerder mot kjønnssykdommer

- Provisorisk anordning av 26. februar 1943, om polititjenesten i Norge under krig, § 6

- Pedersen, Terje Andreas (2012). Vi kalte dem tyskertøser (in Norwegian). Scandinavian Academic Press/Spartacus Forlag. p. 89. ISBN 978-82-304-0086-9.

- Vitanza, Marco Demian (11 Jul 2008). "Idyllisert fortid". Morgenbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 5 Feb 2013.

- Svaar, Torill (10 Dec 2000). "6.oktober...Krigsbrudenes historie i Brennpunkt". NRK (in Norwegian). Retrieved 5 Feb 2013.