Negro Fort

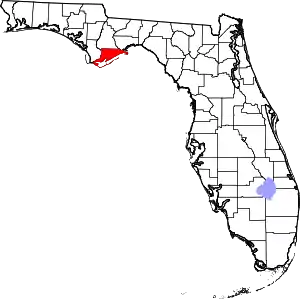

Negro Fort was a short-lived fortification built by the British in 1814, during the War of 1812, in a remote part of what was at the time Spanish Florida. It was intended to support a never-realized British attack on the U.S. via its southwest border,[1]:22 by means of which they could "free all these Southern Countries [states] from the Yoke of the Americans".[1]:40 Built on a militarily significant site overlooking the Apalachicola River, it was the largest structure between St. Augustine and Pensacola.[1]:47 Trading posts of Panton, Leslie and Company and then John Forbes and Company, loyalists hostile to the United States, had existed since the late eighteenth century there and at the San Marcos fort, serving local Native Americans and fugitive slaves. The latter, having been enslaved on plantations in the American South, used their knowledge of farming and animal husbandry to set up farms stretching for miles along the river.

| Battle of Negro Fort | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Seminole Wars | |||||||

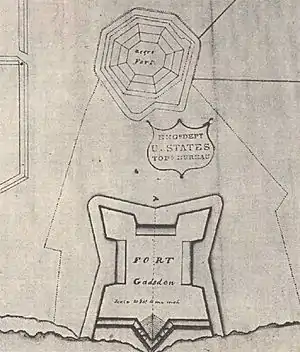

Map of Fort Gadsden, inside the breastwork that surrounded the original Negro Fort. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Creek |

Fugitive slaves Choctaw | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Garçon † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

267 2 gunboats | 334 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3 killed 1 captured | 334 killed, wounded and captured | ||||||

| The fugitive slave and Choctaw casualties include women and children. | |||||||

When withdrawing in 1815, at the end of the war, the British commander, Irishman Edward Nicolls, intentionally left the fully-armed fort in the hands of his former Corps of Colonial Marines. The Corps was made up largely of free negroes and fugitive slaves. Also at the Fort were Creek and Choctaw allies who had served alongside the British during the war. As Nicolls hoped, the fort, near the Southern border of the United States, became a center and symbol of resistance to American slavery. It is the largest and best-known instance before the American Civil War in which armed fugitive slaves resisted white Americans who sought to return them to slavery. (A much smaller example was Fort Mose, near St. Augustine.)

The British did not name the fort. The name "negro fort" was coined by Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins.[1]:76 The Creeks, who were there before Europeans arrived, had rights that enslaved Africans did not have. He led the calls for the fort's destruction.

The fort was destroyed in 1816, at the command of General Andrew Jackson, in the Battle of Negro Fort (also called the Battle of Prospect Bluff or the Battle of African Fort). The Blacks had not been trained in the use of the cannon and other heavy munitions, and they were thus unable to defend themselves. From a boat on the river, the American forces used red-hot shot, trying to start a fire. A shot landed in the powder magazine, which ignited, blowing up the fort and killing over 270 people instantly.

This is the only time in its history in which the United States destroyed a community of escaped slaves in another country.[1]:14 However, the area continued to attract escaped slaves until the U.S. construction of Fort Gadsden in 1818.

The Battle of Negro Fort was the first battle of the Seminole Wars. It made Andrew Jackson a hero to all but abolitionists.

Construction of the fort

Construction of the fort began in May 1814, when the British seized the trading post of John Forbes and Company. By September, there was a square moat enclosing a large field several acres in size. There was a 4 feet (1.2 m) wooden stockade the length of the moat, with bastions at its eastern corners. There was a stone building containing soldiers' barracks and a large warehouse, 48 feet (15 m) by 24 feet (7.3 m). Several hundred feet inland was the magazine, in which stands of arms and 73 kegs of gunpowder were stored.[1]:23

The fort also had "dozens of axes, carts, harnesses, hoes, shovels, and saws", along with many uniforms, belts, and shoes. The British left all these behind.[1]:81–82 There were over a dozen schooners, barques, and canoes, one 45 feet (14 m) long, along with sails, anchors, and other equipment, and "a number of experienced sailors and shipwrights".[1]:93–94

To attract recruits, the British visited the Creek, Seminole, and "negro settlements" along the river and its tributaries, distributing guns, uniforms, and other goods. The Creeks were enthusiastic about this opportunity to attack the United States, whose settlers had taken their land. At the request of the British, they started inviting Blacks to join them. Slaves of the Spanish in Pensacola were also invited, and came by the hundreds, As a result, the British Post was a "beehive of activity" in 1814.[1]:23–24 Commander Nicolls had under his command, at Prospect Bluff, or living up the river, some 3,500 men eager to attack the Americans.[1]:58 Most of the Negroes did not want to return to be slaves of the Spanish in Pensacola, some of them adopting English names and claiming, so they would not be returned, to be fugitives from the United States.[1]:61–63

A refuge for fugitive slaves

Fugitive slaves had been seeking refuge in Florida for generations, where they were well received by the Seminoles and treated as free by the Spaniards if they converted to Catholicism; the origins of the future Underground Railroad are here. The Spaniards wanted their own Pensacola slaves back, but as far as American slaves they did not much care. In any event, they lacked the resources to find and "recover" them, at one point inviting the American slaveowners to catch the fugitives themselves.

Fugitive slaves continued to arrive, seeking in Florida their freedom; they set up a network of farms along the river to keep them supplied. The Seminoles knew how to do this because the Blacks, who had learned on plantations how to farm and care for domestic animals, either taught them or did their farming for them, or both. The Creeks knew nothing of farming and were impoverished; even Nicolls commented on the number of starving, resourceless Creeks who were arriving, and the challenge of feeding them. The Creeks had a champion, Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins, who tried to help them recover their lands. They had never been enslaved and thus did not have to worry about being returned to slavery. They wanted to return to their lands, taken or threatened by white settlers.

The fugitive slave situation became more serious as news of a Negro Fort with weaponry spread through the southern United States.

Negro Fort

The Negro Fort flew the British Union Jack, as the former Colonial Marines considered themselves British subjects.[1]:60–61, 72, 86 The Spaniards continued their policy of leaving the fugitive slaves alone.[1]:8 What was different now was that a corps had had some military training, and was well armed, and had been encouraged by departing abolitionist Nicolls to get others to run away from their owners and join them. The number and ethnicity of men, and in some cases their families, at the Negro Fort was not fixed; they came and went as the unstable political situation evolved. Yet the existence of a fortified, armed sanctuary for fugitive slaves became widely known in the southern United States.

The pro-slavery press in the United States expressed outrage at the existence of Negro Fort.[2]:49 This concern was published in the Savannah Journal:

It was not to be expected that an establishment so pernicious to the Southern states, holding out to a part of their population temptations to insubordination, would have been suffered to exist after the close of the war [of 1812]. In the course of last winter, several slaves from this neighborhood fled to that fort; others have lately gone from Tennessee and the Mississippi Territory. How long shall this evil, requiring immediate remedy, be permitted to exist?[3]

Escaped slaves came from as far as Virginia.[4]:178 The Apalachicola, as was true of other rivers of north Florida, was a base for raiders who attacked Georgia plantations, stealing livestock and helping the enslaved workers escape. Other slaves escaped from the militia units near the border, in which they had been serving. To correct this situation, seen by Southerners as intolerable, in April 1816 the U.S. Army decided to build Fort Scott on the Flint River, a tributary of the Apalachicola. Supplying the fort was challenging because transporting materials overland would have required traveling through unsettled wilderness. The obvious route to supply the Fort was the river. Although technically this was Spanish territory, Spain had neither the resources nor the inclination to defend this remote area. Supplies going to or from the newly-built Fort Scott would have to pass directly in front of the Negro Fort. The boats carrying supplies for the new fort, the Semelante and the General Pike, were escorted by gunboats sent from Pass Christian. The defenders of the fort ambushed sailors gathering fresh water, killing three and capturing one (who was subsequently burned alive); only one escaped.[5] When the U.S. boats attempted to pass the fort on April 27 they were fired upon.[6] This event provided a casus belli for destroying Negro Fort.

Hawkins and other white settlers made contact with Andrew Jackson, seen as the person most capable of doing so. Jackson requested permission to attack, and started preparations. Ten days later, without having received a reply, he ordered Brigadier General Edmund P. Gaines at Fort Scott to destroy Negro Fort. The U.S. expedition included Creek Indians from Coweta, who were induced to join by the promise that they would get salvage rights to the fort if they helped in its capture. On July 27, 1816, following a series of skirmishes, the U.S. forces and their Creek allies launched an all-out attack under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Duncan Clinch, with support from a naval convoy commanded by Sailing Master Jarius Loomis]. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams later justified the attack and subsequent seizure of Spanish Florida by Andrew Jackson as national "self-defense", a response to Spanish helplessness and British involvement in fomenting the "Indian and Negro War". Adams produced a letter from a Georgia planter complaining about "brigand Negroes" who made "this neighborhood extremely dangerous to a population like ours." Southern leaders worried that the Haitian Revolution or a parcel of Florida land occupied by a few hundred blacks could threaten the institution of slavery. On July 20, Clinch and the Creek allies left Fort Scott to assault Negro Fort but stopped short of firing range, realising that artillery (gunboats) would be needed.

Battle of Negro Fort

The Battle of Negro Fort was the first major engagement of the Seminole Wars period, and marked the beginning of General Andrew Jackson's conquest of Florida.[7] Three leaders of the fort were former Colonial Marines who had come with Nicolls (since departed) from Pensacola. They were: Garçon ("boy"), 30, a carpenter and former slave in Spanish Pensacola, valued at 750 pesos;[4]:181 Prince, 26, a master carpenter valued at 1,500 pesos, who had received wages and an officer's commission from the British in Pensacola;[4]:157 and Cyrus, 26, also a carpenter, and literate.[4]:181 Prince may have been the military commander of the same name at the head of 90 free blacks brought from Havana to assist the Spanish defense in St. Augustine during the Patriot War of 1812. As the U.S. expedition drew near the fort on July 27, 1816, black militiamen had already been deployed and began skirmishing with the column before regrouping back at their base. At the same time the gunboats under Master Loomis moved upriver to a position for a siege bombardment. Negro Fort was occupied by about 330 people at the time of the battle. At least 200 were maroons, armed with ten cannons and dozens of muskets. Some were former Colonial Marines.[8] They were accompanied by thirty or so Seminole and Choctaw warriors under a chief. The remaining were women and children, the families of the black militia.[7]

Before beginning an engagement General Gaines first requested a surrender. Garçon, the leader of the fort, refused. Garçon told Gaines that he had orders from the British military to hold the post, and at the same time raised the Union Jack and a red flag to symbolize that no quarter would be given. The Americans considered the Negro Fort to be heavily defended; after they formed positions around one side of the post, the Navy gunboats were ordered to start the bombardment. Then the defenders opened fire with their cannons, but they had not been trained in using artillery, and were thus unable to utilise it effectively.[7] It was daytime when Master Jarius Loomis ordered his gunners to open fire. After five to nine rounds were fired to check the range, the first round of hot shot cannonball, fired by Navy Gunboat No. 154, entered the Fort's powder magazine. The ensuing explosion was massive, and destroyed the entire Fort. Almost every source states that all but about 60 of the 334 occupants of the Fort were instantly killed, and others died of their wounds shortly after, including many women and children.[9] A more recent scholar says the number killed was "probably no more than forty", the remainder having fled before the attack.[10]:288 The explosion was heard more than 100 miles (160 km) away in Pensacola. Just afterward, the U.S. troops and the Creeks charged and captured the surviving defenders. Only three escaped injury; two of the three, an Indian and a Black person, were executed at Jackson's orders.[9] General Gaines later reported that:

The explosion was awful and the scene horrible beyond description. You cannot conceive, nor I describe the horrors of the scene. In an instant lifeless bodies were stretched upon the plain, buried in sand or rubbish, or suspended from the tops of the surrounding pines. Here lay an innocent babe, there a helpless mother; on the one side a sturdy warrior, on the other a bleeding squaw. Piles of bodies, large heaps of sand, broken glass, accoutrements, etc., covered the site of the fort... Our first care, on arriving at the scene of the destruction, was to rescue and relieve the unfortunate beings who survived the explosion.

Garçon, the black commander, and the Choctaw chief, among the few who survived, were handed over to the Creeks, who shot Garçon and scalped the chief. African-American survivors were returned to slavery. There were no white casualties from the explosion. The Creek salvaged 2,500 muskets, 50 carbines, 400 pistols, and 500 swords from the ruins of the fort, increasing their power in the region. The Seminole, who had fought alongside the blacks, were conversely weakened by the loss of their allies. The Creek participation in the attack increased tension between the two tribes.[11] Seminole anger at the U.S. for the fort's destruction contributed to the breakout of the First Seminole War a year later.[12] Spain protested the violation of its soil, but according to historian John K. Mahon, it "lacked the power to do more."[13]

Aftermath

The largest group of survivors, including blacks from the surrounding plantations who were not at the Fort, took refuge further south, in Angola, Florida.[14]:232–233[10]:283–285 Some other refugees founded Nicholls Town [sic] in the Bahamas.[14]:129

Garçon was executed by firing squad because of his responsibility for the earlier killing of the watering party, and the Choctaw Chief was handed over to the Creeks, who scalped him. Some survivors were taken prisoner and placed into slavery under the claim that Georgia slaveowners had owned the ancestors of the prisoners.[15] Neamathla, a leader of the Seminole at Fowltown, was angered by the death of some of his people at Negro Fort so he issued a warning to General Gaines that if any of his forces crossed the Flint River, they would be attacked and defeated. The threat provoked the general to send 250 men to arrest the chief in November 1817 but a battle arose and it became an opening engagement of the First Seminole War.

Anger over the destruction of the fort stimulated continued resistance during the First Seminole War.[14]:235

References

- Clavin, Matthew J. (2019). The Battle of Negro Fort. The rise and fall of a fugitive slave community. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9781479811106.

- Carlisle, Rodney P.; Carlisle, Loretta (2012). Forts of Florida. A Guidebook. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813040127.

- "Fort Negro [sic] (Fort Gadsden)". 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- Smith, Gene Allen (2013). The Slaves' Gamble. Choosing Sides in the War of 1812. Palgrave MacMillen. ISBN 9780230342088.

- Mark F. Boyd (October 1937). "Events at Prospect Bluff on the Appalachicola River, 1808-1818". Florida Historical Quarterly. 16 (2): 78–80. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Casualties: U. S. Navy and Marine Corps Personnel Killed and Wounded in Wars, Conflicts, Terrorist Acts, and Other Hostile Incidents Archived June 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Naval Historical Center, United States Navy.

- Cox, Dale (2014). "Attack on the Fort at Prospect Bluff". exloresouthernhistory.com. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- Cox, Dale (2018). "The Fort at Prospect Bluff (July 11, 1816)". exploresouthernhistory.com. Archived from the original on 2018-02-27. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- Federal Writers' Project (1939), Florida. A Guide to the Southernmost State, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 489

- Saunt, Claudio (1999). A New Order of Things. Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733–1816. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521660432.

- Mahon, 23.

- Mahon, 24.

- Mahon, 23-24.

- Millett, Nathaniel (2013). The Maroons of Prospect Bluff and Their Quest for Freedom in the Atlantic World. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813044545.

- National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, British Fort, Aboard the Underground Railroad, retrieved December 22, 2017

Further reading (most recent first)

- Clavin, Matthew J. (2019). The Battle of Negro Fort: The Rise and Fall of a Fugitive Slave Community. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-1479837335.

- Nuño, John Paul (Fall 2015). "'República de Bandidos': The Prospect Bluff Fort's Challenge to the Spanish Slave System". Florida Historical Quarterly. 94 (2): 192–221. JSTOR 24769178.

- Rivers, Larry Eugene (2012). Rebels and Runaways: Slave Resistance in Nineteenth-Century Florida. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03691-0 – via Project MUSE.

- Millett, Nathaniel (Fall 2012). "Slavery and the War of 1812". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 71 (3): 184–205. JSTOR 42628263.

- Landers, Jane G. (1999). Black Society in Spanish Florida. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 025202446X.

External links

- USDA Forest Service (2011). Historic Fort Gadsden. The Archeology Channel. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- "North America's Largest Act of Slave Resistance", a 2015 lecture by Nathaniel Millett