Nicolas Félix Vandive

Sieur Nicolas-Félix Van Dievoet (/ˈdiːvʊt/) called Vandive (/vɒ̃dɪv/), écuyer, (c.1710–1792) was a French court official and nobleman.[1]

Nicolas Félix Vandive | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms | |

| Born | 1710 |

| Died | 1 June 1792 Paris |

| Nationality | |

| Occupation | court official |

| Title | Écuyer |

| Parent(s) | Balthazar-Philippe Vandive and Françoise-Edmée de La Haye |

| Family | Vandive family |

He was court clerk at the Grand Conseil (1743) and of the Conseil du Roi (King's Council), lawyer at the Parlement de Paris (Parliament of Paris) (cited in 1761) and conseiller notaire et secrétaire Maison et Couronne de France près la Cour du Parlement (counsellor, notary and secretary at the French Court for the Court of the Parliament).

Biography

Origins

He was a member of the Vandive family, a parisian family of goldsmiths, a branch of the Van Dievoet family of Brussels. His father was the goldsmith Balthazar Philippe Vandive, who was consul of Paris in 1739.

His grandfather was Philippe van Dievoet called Vandive (1654-1738), goldsmith of the King, counsellor of the King, officier de la Garde Robe du Roi (officer of the King's wardrobe), consul of Paris, trustee of the Hôtel de ville of Paris.

His great-uncle was the sculptor Peter van Dievoet (1661-1729).

Career

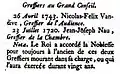

Nicolas-Félix Vandive was cited as early from 26 April 1743, court clerk at the Grand Conseil, which conferred personal Nobility upon him from 1743 and hereditary Nobility from 1763 after 20 years on the job.[2] The Almanach Royal of 1789 still mentions him as court clerk at the Grand Conseil.[3]

Thanks to the Edict given at Versailles on 22 May 1775, which fixed the finances of the Grand Conseil, we can read that "We have also fixed the finances of the offices of first and principal clerk of the audience in our Grand Conseil to which the sieur Vandive is provided, at the sum of 25 thousand livres (pounds)."[4]

He also exerted the ennobling office of conseiller notaire et secrétaire Maison et Couronne de France près la Cour du Parlement (counsellor, notary and secretary at the French Court for the Court of the Parliament). He succeeded in 1774, Étienne Timoléon Isabeau de Montval, who was guillotined in Paris in year II.[5]

The death of King Louis XV

During the last illness of Louis XV, Vandive was sent, on Sunday 1 May 1774 by the Parlement de Paris to inquire on the health of the monarch, as the personal journal of Parisian bookseller Siméon-Prosper Hardy tells us: "The new court of the Parlement, according to ordinary practice, deputised Vandive, one of the first and principal court clerk of the Grand Chambre and of its notary-secretaries, to go to Versailles to obtain news on the King's health. But the secretary could only do this on the following Tuesday, because the Monday 2 May was a respected holiday."[6] And Jean Cruppi in his biography of Linguet writes: "At the Palace, word was suddenly spreading that Louis XV was gravely ill. The Parlement, anxious, and feeling itself as ill as the King, extraordinarily assembled itself. On Tuesday 3 May, they sent their secretary, the sieur Vandive, to Versailles to obtain news of the King. The sieur Vandive, at his return, declared being received by the Duke of Aumont whom told him that the state of the King was Better. Despite this news, on 10 May (1774), we learned that the King was dead."[7]

Gallery

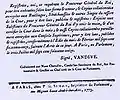

Proof of Nobility

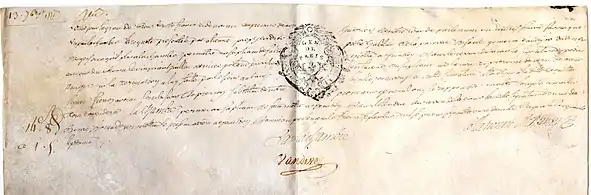

Proof of Nobility Printed letter patent of the King, signed Vandive

Printed letter patent of the King, signed Vandive Document from the Parlement signed Vandive

Document from the Parlement signed Vandive Document signed Vandive

Document signed Vandive Almanach Royal of 1772 mentioning Vandive

Almanach Royal of 1772 mentioning Vandive Parlement document dated 28 July 1774, which condemns Joseph Grodemanche called Bellehumeur (1/4)

Parlement document dated 28 July 1774, which condemns Joseph Grodemanche called Bellehumeur (1/4) Parlement document dated 28 July 1774, which condemns Joseph Grodemanche called Bellehumeur (2/4)

Parlement document dated 28 July 1774, which condemns Joseph Grodemanche called Bellehumeur (2/4) Parlement document dated 28 July 1774, which condemns Joseph Grodemanche called Bellehumeur (3/4)

Parlement document dated 28 July 1774, which condemns Joseph Grodemanche called Bellehumeur (3/4) Parlement document dated 28 July 1774, which condemns Joseph Grodemanche called Bellehumeur (4/4)

Parlement document dated 28 July 1774, which condemns Joseph Grodemanche called Bellehumeur (4/4)

Bibliography

- L'Etat de la France, 4th volume, Paris, 1749, p. 383.

- Mercure de France, February 1760, p. 219.

- Helvétius, Correspondance générale d'Helvétius, édition critique par Peter Allan et alii, 3rd volume, 1761–1774, p. 479.

- Journal politique de Bouillon, Bouillon, 1771.

- France Sovereign, Lettres patentes du roi, pour la construction des bâtimens devant servir à, 1715–1774.

- MM. Jourdan, Isembert, Decrusy, Recueil général des anciennes lois françaises- depuis l'an 420 jusqu'à la révolution de 1789, Paris, 1824, 23rd Volume, p. 173 and p. 175.

- Félix Lazare and Louis Lazare, Dictionnaire administratif et historique des rues de Paris et de ses monuments, Paris, 1844, p. 660.

- Jean Cruppi, Un avocat journaliste au XVIIIe siècle: Linguet, Paris, published by Hachette, 1895, chapter 8 (1774-1775), Mort de Louis XV, p. 352.

- Alfred Détrez, Aristocrates et joailliers sous l'ancien régime, in La Revue (former Revue des Revues), 78th volume, Paris, 1908, p. 471.

- Siméon-Prosper Hardy, Mes loisirs, Paris, 1912, p. 266.

- Ludovic de Colleville (comte) and François Saint-Christo, Les ordres du roi, Paris, Jouve editions, 1924.

- Robert Villers, L'organisation du parlement de Paris et des conseils supérieurs d'après la réforme de Maupeou, Paris, 1937, p. 109.

- Alain van Dievoet, « Généalogie de la famille van Dievoet originaire de Bruxelles, dite van Dive à Paris », in Le Parchemin, edited by the Genealogical and Heraldic Office of Belgium, Brussels, 1986, n° 245, pp 273–293.

- Alain Van Dievoet, « Van Dive, joaillier du Dauphin », in : L'intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux : mensuel de questions et réponses sur tous sujets et toutes curiosités, Paris, n° 470, 1990, columns 645–650.

- Béatrice de Andia and Nicolas Courtin, L'île Saint-Louis : Action Artistique de la Ville de Paris, Paris, 1997, p. 112.

- Alain van Dievoet, « Quand le savoir-faire des orfèvres bruxellois brillait à Versailles », in : Cahiers bruxellois, Brussels, 2004, pp. 19–66 (Concernant Nicolas Félix Van Dievoet dit Vandive, voir p. 38).

- Hélène Cavalié née d'Escayrac-Lauture, Pierre Germain dit le Romain (1703-1783). Vie d'un orfèvre et de son entourage, Paris, 2007, thesis of the École des Chartes, 1st volume, pp. 209, 210, 345, 350, 429, 447.

- Nicolas Félix Vandive, correspondance by Nicolas Félix Vandive, Electronic Enlightenment Project.

- Siméon-Prosper Hardy, Mes Loisirs, ou Journal d'événemens tels qu'ils parviennent à ma connoissance, edited by Daniel Roche and Pascal Bastien, Presses de l'université Laval, 12 volumes, 2008 to ..., 2nd volume, p. 252 et 283, Paris : éditions Hermann, 2nd volume, p. 252 and p. 183 ; 3rd volume, p. 418 and p. 431. (index sub verbo: Vandive, Nicolas Félix, greffier de l'audience au Grand Conseil).

References

- Title unknown, L'Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, Issues 596-606, Page 1117, 2002. "Nicolas Félix Vandive. Paris, paroisse Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois, est cité comme greffier de l'audience du conseil du roi procuration de Etienne Duchemin de La Tour, chevalier, capitaine de grenadiers"

- L'État de la France, volume IV, Paris, at Ganeau, rue Saint Severin, près l’Église, aux Armes de Dombes et à Saint-Louis, avec privilège du roi, 1749, p.383: « Le Roi a accordé la Noblesse pour toujours à l'ancien de ces deux Greffiers mourant dans sa charge, ou qui l'aura exercée durant vingt ans »

- Almanach royal de 1789, Grand Conseil

- In French: "Nous avons pareillement fixé les finances des offices de premier et principal commis du greffe de l'audience de notre Grand Conseil dont le sieur Vandive étoit pourvu, à la somme de vingt-cinq mille livres ».

- (L. Prudhomme, Dictionnaire des individus envoyés à la mort judiciairement..... pendant la Révolution, Paris, 1796, tome II, p. 2

- In French: « La nouvelle cour du Parlement n'avoit pas manqué, suivant l'usage ordinaire, de députer le nommé Vandive, l'un des premiers principaux commis au greffe de la Grand Chambre et de ses notaires secrétaires, pour aller à Versailles savoir des nouvelles de la santé du Roi. Mais ce secrétaire ne pouvoit rendre compte de sa mission à l'inamovible compagnie que le mardi suivant, attendue la vacance accoutumée du lundi 2 mai. »

- In French: « Au Palais, le bruit se répand tout à coup que Louis XV est gravement malade. Le Parlement, anxieux, et se sentant lui-même aussi malade que le roi, s'assemble extraordinnairement. Le mardi 3 mai, "Messieurs" envoient leur secrétaire, le sieur Vandive, à Versailles pour prendre des nouvelles du roi. Le sieur Vandive, à son retour, déclare qu'il a été reçu par le duc d'Aumont lequel a bien voulu lui dire que l'état du roi est meilleur. Malgré cela, le 10 mai (1774), on apprend que le roi est mort. »