North Carolina's congressional districts

North Carolina is currently divided into 13 congressional districts, each represented by a member of the United States House of Representatives. After the 2000 Census, the number of North Carolina's seats was increased from 12 to 13 due to the state's increase in population.

Constitutionality of the 1990 redistricting

After the 1990 Census, the US Department of Justice directed North Carolina under VRA preclearance to submit a map with two majority-minority districts. The resultant map with two such districts, the 1st and 12th, was the subject of lawsuits by voters who claimed that it was an illegal racial gerrymander. A three judge panel of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina dismissed the suit, which was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. On June 28, 1993, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Shaw v. Reno, found that the 12th congressional district was an unlawful racial gerrymander. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor's opinion found that if a district's shape, like the 12th's, was "so bizarre on its face that it is 'unexplainable on grounds other than race'," that it would be subject to strict scrutiny as a racial gerrymander, and remanded the case to the Eastern District of North Carolina.

On August 22, 1994 the District Court on remand in Shaw v. Hunt found that the 12th Congressional District was an racial gerrymander (as the Supreme Court had directed), but ruled that the map satisfied strict scrutiny due to the compelling interest of compliance with the Voting Rights Act and increasing black political power.[1] This was again appealed to the Supreme Court, which reversed the District Court on June 13, 1996 and found that the North Carolina plan violated the Equal Protection Clause and that the 12 District did not satisfy a compelling interest.

Constitutionality of the 1997 redistricting

North Carolina drew a new map following Shaw v. Hunt, and the new maps were duly challenged. A three judge panel of the Eastern District of North Carolina granted summary judgment that the new boundaries were an illegal racial gerrymander.[2] This was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in Hunt v. Cromartie on May 17, 1999 unanimously ruled that the District Court was in error to grant summary judgment and remanded the case for the District Court to hold a trial. After the ensuing trial, the District Court ruled that the 12th District was an illegal racial gerrymander on March 7, 2000.[3] This was again duly appealed, now as Easley v. Cromartie, and the U.S. Supreme Court on April 18, 2001 reversed the District Court and ruled that the 12th District boundaries were legal. The Court's opinion held that the 12th District was not a racial gerrymander, but that it was a partisan gerrymander, which was a political question that the courts should not rule upon. Justice O'Connor, the author of Shaw v. Hunt was the swing justice who switched sides to uphold the district.

Constitutionality of the 2010 redistricting

In February 2016, a three-judge panel of U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit and U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina judges ruled that the 1st and 12th districts' boundaries were unconstitutional and required new maps to be drawn by the legislature to be used for the 2016 election.[4] On 22 May 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Cooper v. Harris, agreed that the 1st and 12th congressional district boundaries were unlawful racial gerrymanders, the latest in a series of cases dating back to 1993 by different parties challenging various configurations of those districts since their first creation.[5][6]

In January 2018 a federal court struck down North Carolina's congressional map, declaring it unconstitutionally gerrymandered to favor Republican candidates. The court ordered that the North Carolina General Assembly must redraw the district maps prior to the 2018 congressional elections.[7] However, the United States Supreme Court stayed the federal court order pending review,[8] and in June 2019, the Supreme Court ruled in Rucho v. Common Cause, by a 5–4 vote, that partisan gerrymandering is a "political question" that the federal courts have no place to rule on.[9][10]

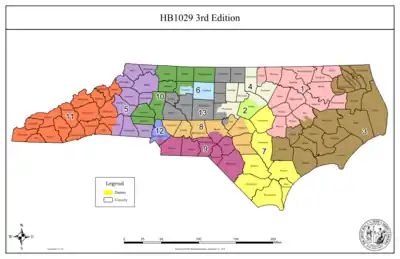

Constitutionality of the 2017 redistricting

On 3 September 2019 a three-judge panel in a 357 page ruling unanimously struck down the Republican-led state legislature drawn 2017 enacted maps,[12][13] which were drawn to replace the 2011 maps which were also ruled unconstitutional and thrown out on racial grounds.[14] The court ruled that the state House and state Senate districts maps were such an extreme partisan gerrymander that they violated the state constitution. In the ruling the state legislature was ordered by the court to immediately start drawing new maps; the court demanded that they be drawn based on criteria like population, contiguity, and county lines. Districts had to be drawn without "partisan considerations and election results data," and done so in plain view, a departure from the closed-door processes the ruling eschews. "At a minimum, that would require all map drawing to occur at public hearings, with any relevant computer screen visible to legislators and public observers." The judges said the new maps had to be completed in two weeks; they also said they reserved the right to move the 2020 primary election if needed.[15]

In October 2019, a panel of three judges ruled that the map was an unfair partisan gerrymander and had to be redrawn.[16] On 15 November 2019 the North Carolina General Assembly passed a bill that drew new districts that were used for the 2020 elections. The 2nd and 6th districts were drawn to be more favorable to Democrats under the new proposal.[17] On 2 December 2019 a three-judge panel ruled that newly Republican-drawn congressional district maps completed in November 2019 would stand for federal elections in 2020. The maps allowed to stay in place on 2 December 2019 would only be used once. After the 2020 United States Census the congressional districts will be redrawn again in 2021.[18]

Current districts and representatives

List of members of the North Carolinian United States House delegation, their terms, their district boundaries, and the districts' political rating according to the CPVI. The delegation has a total of 13 members, with 8 Republicans, and 5 Democrats. These districts reflect the 2016 proposal which was used in the 2016 and 2018 elections. New districts drawn and passed by the North Carolina General Assembly were used for the 2020 elections.

| District | Representative | Party | CPVI | Incumbency | District map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

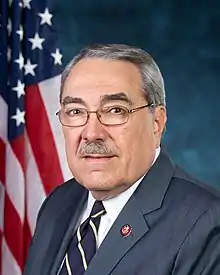

| 1st |  G. K. Butterfield |

Democratic | D+4 | 20 July 2004 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 2nd |  Deborah Ross |

Democratic | D+9 | 3 January 2021 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

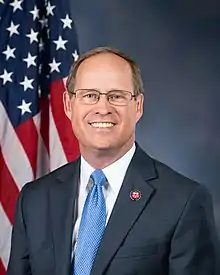

| 3rd |  Greg Murphy |

Republican | R+12 | 17 September 2019 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 4th | .jpg.webp) David Price |

Democratic | D+14 | 3 January 1997 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 5th |  Virginia Foxx |

Republican | R+18 | 3 January 2005 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 6th |  Kathy Manning |

Democratic | D+9 | 3 January 2021 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 7th |  David Rouzer |

Republican | R+11 | 3 January 2015 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 8th |  Richard Hudson |

Republican | R+5 | 3 January 2013 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 9th | .jpg.webp) Dan Bishop |

Republican | R+7 | 17 September 2019 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 10th | .jpg.webp) Patrick McHenry |

Republican | R+20 | 3 January 2005 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 11th |  Madison Cawthorn |

Republican | R+9 | 3 January 2021 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 12th | .jpg.webp) Alma Adams |

Democratic | D+18 | 4 November 2014 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

| 13th |  Ted Budd |

Republican | R+19 | 3 January 2017 – present | .tif.png.webp) |

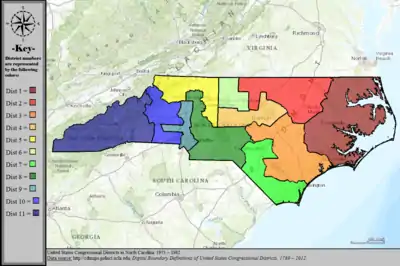

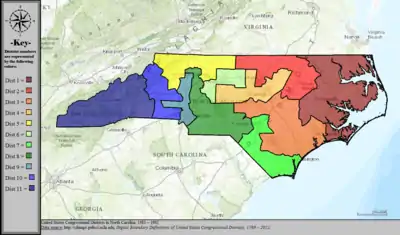

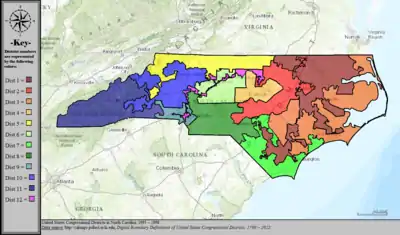

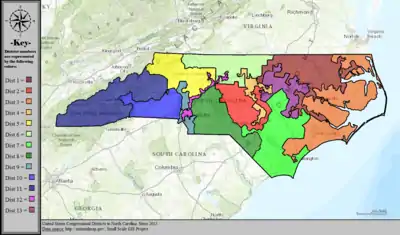

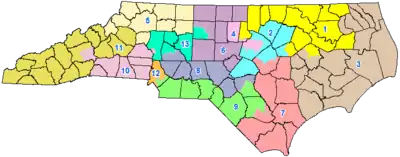

Historical and present district boundaries

Table of United States congressional district boundary maps in the State of North Carolina, presented chronologically.[19] All redistricting events that took place in North Carolina between 1973 and 2013 are shown, congressional composition is listed on the right.

| Year | Statewide map | Charlotte highlight | Congressional Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973–1982 |  |

%252C_1973_%E2%80%93_1982.tif.png.webp) |

1973–1975: 7 Democrats, 4 Republicans

1975–1977: 9 Democrats, 2 Republicans 1977–1979: 9 Democrats, 2 Republicans 1979–1981: 9 Democrats, 2 Republicans 1981–1983: 7 Democrats, 4 Republicans |

| 1983–1992 |  |

%252C_1983_%E2%80%93_1992.tif.png.webp) |

1983–1985: 9 Democrats, 2 Republicans

1985–1987: 6 Democrats, 5 Republicans 1987–1989: 8 Democrats, 3 Republicans 1989–1991: 8 Democrats, 3 Republicans 1991–1993: 7 Democrats, 4 Republicans |

| 1993–1998 |  |

%252C_1993_%E2%80%93_1998.tif.png.webp) |

1993–1995: 8 Democrats, 4 Republicans

1995–1997: 4 Democrats, 8 Republicans 1997–1999: 6 Democrats, 6 Republicans |

| 1999–2000 |  |

%252C_1999_%E2%80%93_2000.tif.png.webp) |

1999–2001: 5 Democrats, 7 Republicans |

| 2001–2002 |  |

%252C_2001_%E2%80%93_2002.tif.png.webp) |

2001–2003: 5 Democrats, 7 Republicans |

| 2003–2013 |  |

%252C_2003_%E2%80%93_2013.tif.png.webp) |

2003–2005: 6 Democrats, 7 Republicans

2005–2007: 6 Democrats, 7 Republicans 2007–2009: 7 Democrats, 6 Republicans 2009–2011: 8 Democrats, 5 Republicans 2011–2013: 7 Democrats, 6 Republicans |

| 2013–2017 |  |

%252C_since_2013.tif.png.webp) |

2013–2015: 4 Democrats, 9 Republicans

2015–2017: 3 Democrats, 10 Republicans |

| 2017-2021 |  |

2017-2019: 3 Democrats, 10 Republicans

2019-2021: 3 Democrats, 10 Republicans | |

| 2021-2023 |  |

%252C_2021_-_2023.tif.png.webp) |

2021-2023: 5 Democrats, 8 Republicans |

See also

References

- https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/861/408/2261731/

- https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/34/1029/2462399/

- https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/133/407/2292720/

- Blythe, Anne (5 February 2016). "Federal court invalidates maps of two NC congressional districts". The Charlotte Observer. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Supreme Court tosses Republican-drawn North Carolina voting districts". Reuters. 22 May 2017. Archived from the original on 22 May 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Stern, Mark Joseph (22 May 2017). "In Cooper v. Harris, the Supreme Court strikes a blow against racial redistricting". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Blinder, Alan (2018). "North Carolina Congressional Map Ruled Unconstitutionally Gerrymandered". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "Supreme Court Blocks Redrawing of North Carolina Congressional Maps". Reuters. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Liptak, Adam. "Supreme Court Says Constitution Does Not Bar Partisan Gerrymandering". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/18pdf/18-422_9ol1.pdf

- http://www.ncleg.net/representation/Content/Plans/PlanPage_DB_2016.asp?Plan=2016_Contingent_Congressional_Plan_-_Corrected&Body=Congress

- PDF.

- "Common Cause v. Representative David R Lewis, et al. Judgement" (PDF). CommonCause.org. 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Doran, Will (3 September 2019). "After maps struck down in NC gerrymandering lawsuit, top Republican leader won't appeal". Herald Sun. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Timm, Jane C. (4 September 2019). "North Carolina judges slam GOP gerrymandering in stinging ruling, reject district maps". NBC News. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Williams, Pete (28 August 2019). "Court throws out North Carolina's congressional district maps". NBC News. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "House Bill 1029 / SL 2019-249 (2019-2020 Session) - North Carolina General Assembly". www.ncleg.gov.

- Timm, Jane C. (2 December 2019). "In blow to North Carolina Democrats, court rules new GOP-drawn voting maps can be used for 2020". NBC News. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "Digital Boundary Definitions of United States Congressional Districts, 1789–2012". Retrieved 18 October 2014.