Novgorod Chronicle

The Novgorod First Chronicle (Russian: Новгородская первая летопись) or The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016–1471[1] is the most ancient extant Old Russian chronicle of the Novgorodian Rus'. It reflects a tradition different from the Primary Chronicle of the Kievan Rus'. As was first demonstrated by Aleksey Shakhmatov, the later editions of the chronicle reflect the lost Primary Kievan Code (Начальный Киевский свод) of the late 11th century, which contained much valuable information that was suppressed in the later Primary Chronicle. However, an author to the chronicle was never established.

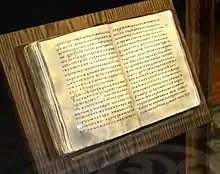

The earliest extant copy of the chronicle is the so-called Synod Scroll, dated to the second half of the 13th century. First printed in 1841, it is currently preserved in the State Historical Museum. It is the earliest known manuscript of a major East Slavic chronicle, predating the Laurentian Codex of the Primary Chronicle by almost a century. In the 14th century, the Synod Scroll was continued by the monks of the Yuriev Monastery in Novgorod.

Other important copies of the Novgorod First Chronicle include the Academic Scroll (241 lists, 1444), Commission Scroll (320 lists, mid-15th century), Trinity Scroll (1563), and Tolstoy Scroll (208 lists, 1720s).

Parallels with pagan beliefs

Many historians have paid attention to the information contained in the Novgorod chronicle about the acts of the Volkhvs (Magi), which is mentioned in 1024 and 1071.

Historian Igor Froyanov cites as an example a scene from the Novgorod Chronicle, where the Magi talk about the creation of man. According to legend, under the year 1071, two Magi appeared in Novgorod and began to sow turmoil, claiming that soon the Dnieper will flow backwards and the land will move from place to place.[2]

Yan Vyshatich asked: "how do you think man came to be?" The Magi answered: "God bathed in the bath and sweated, wiped himself with a rag and threw it from heaven to the earth; and the devil created man, and God put his soul into him. Therefore, when a person dies, the body goes to the earth, and the soul goes to God"

Froyanov was the first to draw attention to the similarity of the text with the Mordovian-Finn legend about the creation of man by God (Cham-Pas) and the devil (Shaitana). In the retelling of Melnikov-Pechersky, this legend sounds like this:

Shaitan modeled the body of a man from clay, sand and earth; he came out with a pig, then a dog, then reptiles. Shaitan wanted to make a man in the image and likeness of Cham-Pas. Then Shaitan called a mouse-bird and ordered it to build a nest in one end of the towel with which Cham-Pas wipes himself when he goes to the bath, and to breed children there: one end will become heavier and the towel with a carnation from the uneven weight will fall to the ground. Shaitan picked up the fallen towel and wiped his cast with it, and the man received the image and likeness of God. After that, Shaitan began to revive a person, but he could not put a living soul into him. The soul was breathed into the man by Cham-Pas. There was a long dispute between Shaitan and Cham-Pas: who should a person belong to? Finally, when Cham-pas got tired of arguing, he offered to divide the person, after the death of a person, the soul should go to heaven to Cham-pas, who blew it, and the body rots, decomposes and goes to Shaitan.

The similarity of the legend with the words of the Magi under the year 1071 (presumably they were of Fino-Ugric origin) indicates that the worldview of the Magi of that period was no longer pagan, but was a symbiosis of Christianity with folk beliefs.[5]

Influence

The text of the First Novgorod chronicle was repeatedly used in other Novgorod chronicles. It became one of the main sources of the so-called Novgorodsko-Sofiysky Svod, which in turn served as the protograph of the Fourth Novgorod and First Sofia Chronicles. The Novgorodsko-Sofiysky Svod was included in the all-Russian chronicle of the XV-XVI centuries. Independently it was reflected in the Tver chronicle.[6]

References

- The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016–1471

- Igor Froyanov. About the events of 1227-1230 in Novgorod // Ancient Russia

- Novgorod first letopis. P.172

- Melnikov. Essays of Mordovia. Russian. Vestn., vol. 71, 1867, No. 9, pp. 229–230. Also: Vasily Klyuchevsky. Course of Russian history, part 1, p. 37

- Galkovsky N. M. The Struggle of Christianity with the remnants of paganism in Ancient Russia. Vol. 1. Chapter IV- Kharkiv:Епархіальная типографія, 1916.

- Alexey Gippius The Novgorod letopis and its authors: the history and structure of the text in linguistic coverage // Linguistic source studies and history of the Russian language. 2004-2005. - Moscow, 2006

Online editions

External links

Media related to Novgorod First Chronicle at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Novgorod First Chronicle at Wikimedia Commons