Nuestra Señora de la Concepción

Nuestra Señora de la Concepción (Spanish: "Our Lady of the (Immaculate) Conception") was a 120-ton Spanish galleon that sailed the Peru–Panama trading route during the 16th century. This ship has earned a place in maritime history not only by virtue of being Sir Francis Drake's most famous prize, but also because of her colourful nickname, Cagafuego ("fireshitter").[1]

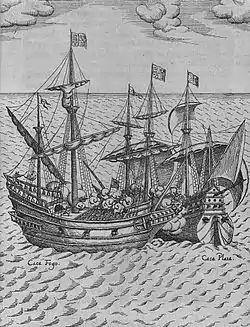

Capture Of Cagafuego (1626) engraving by Friedrich Hulsius | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Nuestra Señora de la Concepción |

| Nickname(s): | Cagafuego |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Galleon |

| Tons burthen: | 120 tons (bm) |

| Propulsion: | Sails |

Capture by Sir Francis Drake

At the helm of his ship Golden Hind, Sir Francis Drake had slipped into the Pacific Ocean via the strait of Magellan in 1578 without the knowledge of the Spanish authorities in South America. Privateers and pirates were common during the 16th century throughout the Spanish Main but were unheard of in the Pacific. Accordingly, the South American settlements were not prepared for the attack of "el Draque" (Spanish pronunciation of Sir Francis' last name), as Drake was to be known to his Spanish victims. During this trip, Drake pillaged El Callao (Peru's main port) and was able to gather information regarding the treasure ship Cagafuego, which was sailing toward Panama laden with silver and jewels.[1]

Golden Hind caught up with Cagafuego on 1 March 1579, in the vicinity of Esmeraldas, Ecuador. Since it was the middle of the day and Drake did not want to arouse suspicions by reducing sails, he trailed some wine casks behind Golden Hind to slow her progress and allow enough time for night to fall. In the early evening, after disguising Golden Hind as a merchantman, Drake finally came alongside his target and, when the Spanish captain San Juan de Antón refused to surrender, opened fire.[1]

Golden Hind's first broadside took off Cagafuego's mizzenmast. When the English sailors opened fire with muskets and crossbows, Golden Hind came alongside with a boarding party. Since they were not expecting English ships to be in the Pacific, Cagafuego's crew was taken completely by surprise and surrendered quickly and without much resistance. Once in control of the galleon, Drake brought both ships to a secluded stretch of coastline and over the course of the next six days unloaded the treasure.[2]

Drake was pleased at his good luck in capturing the galleon, and he showed it by dining with Cagafuego's officers and gentleman passengers. He offloaded his captives a short time later, and gave each one gifts appropriate to their rank, as well as a letter of safe conduct.[2] Laden with the treasure from Cagafuego, Golden Hind continued its voyage first to New Albion, then westward, completing the second circumnavigation of the earth by returning to Plymouth, England, on 26 September 1580.[3]

Wrecking

The vessel was wrecked in 1638 in severe weather off the island of Saipan while travelling from Manila to Acapulco laden with Cambodian ivory, Chinese silks and rugs, cotton from India, camphor from Borneo, spices from the Spice Islands, and precious jewels from Siam, Burma, and Ceylon. According to some, but not all sources, all of the 400 souls aboard her perished, and her ballast and treasures were lost to the sea.[4]

Another source states that on August 10, 1638 the Manila Galleon Nuestra Señora de la Concepcion left Manila Bay during the typhoon season. Concepcion was carrying one of the largest cargoes ever loaded. Juan Francisco de Corcuera, the young nephew of the Governor of the Philippines, was the captain. A typhoon blew the Concepcion off course. With its masts destroyed, it was driven onto the rocks at Agingan Point, Saipan. Many of the crew, comprising Spaniards, Mexicans, and Filipinos, were saved. Some were picked up by passing galleons in later years. Other survivors lived on the island for the rest of their lives. Six men from the Concepcion were saved by a Maga 'lahi of Tinian named Taga. After the rescue, Taga had a vision of a woman holding a baby. Esteban Ramos, who was on the Concepcion, wrote:

"...this Indio came out one day quite exhilarated. "Oy, Oy. What can this be?" he said. "Much fire, much light, a young woman with a child in her arms surrounded by light, and she has told me that you are good people; to help you return to your country, so that you may bring us priests, who will teach us..."

The ship's nickname of "Cagafuego"

Nuestra Señora de la Concepción was reportedly nicknamed Cagafuego, meaning "shitfire" (or "fireshitter"), by her crew. The Early Modern Spanish verb caca "defecate" was derived from the Latin cacare.[6] (Caca mutated into caga in modern Spanish and the formation "shitfire" into "cagafuego".)

There was a contemporaneous cognate in the Florentine Italian dialect: cacafuoco, meaning "handgun".[7] From about 1600, the word spitfire was used in English, initially as an alternative term for "cannon".[7] Spitfire may have originated as a minced calque of cacafuoco,[7] although a folk etymology has long claimed that it originated as cagafuego, in reference to Nuestra Señora de la Concepción. In the 1670s, spitfire acquired the additional meaning of an "irascible, passionate person". In 1776, the British Royal Navy commissioned the first of more than 10 vessels named HMS Spitfire. Since the late 1930s, however, the word has been more famously associated with the Supermarine Spitfire fighter aircraft and the Mexican Spitfire film series, starring Lupe Vélez.

References

Citations

- Coote, p.156

- Coote, p.157

- Coote, p.182

- https://wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?138071

- Source:"History of the Mariana Islands to Partition " by Don A. Farrell Edited by Ivan Propst 2011 pg 141

- http://lema.rae.es/drae/?val=cagar

- Online Etymology Dictionary, 2001–2017, "spitfire (n.)" (18 December 2017).

Sources

- Coote, Stephen (2003). Drake: The Life and Legend of an Elizabethan Hero. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 0-312-34165-2.

- Cordingly, David (1995). Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-15-600549-2.

- Williams, Neville (1975). The Sea Dogs: Privateers, Plunder and Piracy in the Elizabethan Age. London.