Nueva Planta decrees

The Nueva Planta decrees (Spanish: Decretos de Nueva Planta, Catalan: Decrets de Nova Planta) were a number of decrees signed between 1707 and 1716 by Philip V, the first Bourbon king of Spain, during and shortly after the end of the War of the Spanish Succession by the Treaty of Utrecht.

Historical context

Angered by what he saw as sedition by the Aragonese, who had supported the claim of Charles of Austria to the Spanish thrones during the war and taking his native France as a model of a centralised state, Philip V suppressed the institutions, privileges, and the ancient charters (Spanish: fueros, Catalan: furs) of almost all the areas that were formerly part of the Crown of Aragon (Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, and the Balearic Islands). The decrees ruled that all the territories in the Crown of Aragon except the Aran Valley were to be ruled by the laws of Castile ("the most praiseworthy in all the Universe" according to the 1707 decree), embedding those regions into a new and nearly uniformly administered, centralised Spain.

The other historic territories (Navarre and the other Basque territories) supported Philip V initially, whom they saw as belonging to the lineage of Henry III of Navarre, but after Philip V's military campaign to crush the Basque uprising, he backed down on his intent to suppress home rule.

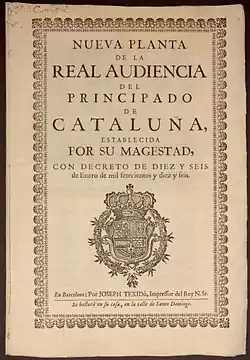

The acts abolishing the charters were promulgated in 1707 in Valencia and Aragon,[1] in 1715 in Majorca and the other Balearic Islands (with the exception of Menorca, then a possession of the Kingdom of Great Britain) and finally in Catalonia on 16 January 1716.[1]

Effects of the decrees

The decrees effectively created a Spanish citizenship or nationality, which judicially no longer distinguished between Castilian and Aragonese with respect to both rights and law. They abolished internal borders and customs except for the Basque territory, giving grant to all Spaniards to trade with American colonies (not only Castilians, as before). Henceforth, top civil servants were appointed directly from Madrid, the King's court city, and most institutions in those territories were abolished. Court cases could only be presented and argued in Castilian, which became the sole language of government, displacing Latin, Catalan and other Spanish languages.

See also

- Acts of Union 1707 between Scotland and England, creating the United Kingdom

- Bourbon Reforms of Philip V and his successors

- Catalan Constitutions

- Furs of Valencia

References

- This article draws on material from the corresponding article in the Spanish Wikipedia, accessed January 2006.

- Stanley G. Payne. "Chapter 16, The Eighteenth-Century Bourbon Regime in Spain". A History of Spain and Portugal - Vol. 2. Retrieved 17 April 2008.

External links

- Documents about the case of the catalans dated on 1714, at the House of Lords, UK.

- Journal of the House of Lords: volume 19, 2 August 1715, Further Articles of Impeachment against E. Oxford brought from H.C. Article VI.

- Extract from the Decree of abolition of the fueros of Aragon and Valencia from Wikisource

- Decree of 16 January 1716 (facsimile)