Languages of Spain

The languages of Spain (Spanish: lenguas de España), or Spanish languages (Spanish: lenguas españolas),[2] are the languages spoken or once spoken in Spain.

| Languages of Spain | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official | |

| Regional |

|

| Immigrant | Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, Darija, Berber, Romanian, English, German, French, Italian, Chinese, Bulgarian, Ukrainian,Russian,Wolof, Urdu, Hindustani, Cantonese. (see immigration to Spain) |

| Signed | Spanish Sign Language Catalan Sign Language Valencian Sign Language |

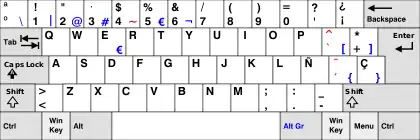

| Keyboard layout | |

| Source | [1] |

Most languages spoken in Spain belong to the Romance language family, of which Spanish is the only language which has official status for the whole country.[3] Various other languages have co-official or recognised status in specific territories,[4] and a number of unofficial languages and dialects are spoken in certain localities.

Present-day languages

In terms of the number of speakers and dominance, the most prominent of the languages of Spain is Spanish (Castilian), spoken by about 99% of Spaniards as a first or second language.[5] According to a 2019 Pew Research survey, the most commonly spoken languages at home other than Spanish were Catalan in 8% of households, Valencian 4%, Galician 3% and Basque in 1% of homes.[6]

Distribution of the regional co-oficial languages in Spain:

- Aranese, a variety of Occitan co-official in Catalonia.[7] It is spoken in the Pyrenean comarca of the Aran Valley (Val d'Aran), in north-western Catalonia. It is a variety of Gascon, a southwestern dialect of the Occitan language.

- Basque, co-official in the Basque Country and northern Navarre (see Basque-speaking zone). Basque is the only non-Romance language (as well as non-Indo-European) with an official status in mainland Spain.

- Catalan, co-official in Catalonia and in the Balearic Islands. It is recognised but not official in Aragon, in the area of La Franja. Outside of Spain, it is the official language of Andorra; it is also spoken in the Pyrénées-Orientales department in southernmost France, and in the city of Alghero on the island of Sardinia, where it's co-official with Italian. [8]

- Valencian (variety of Catalan), co-official in the Valencian Community. Not all areas of the Valencian Community, however, are historically Valencian-speaking, particularly the western side. It is also spoken without official recognition in the area of Carche, Murcia.

- Galician, co-official in Galicia and recognised, but not official, in the adjacent western parts of the Principality of Asturias (as Galician-Asturian) and Castile and León.

Spanish is official throughout the country; the rest of these languages have legal and co-official status in their respective communities and (except Aranese) are widespread enough to have daily newspapers and significant book publishing and media presence. Catalan and Galician are the main languages used by the respective regional governments and local administrations. A number of citizens in these areas consider their regional language as their primary language and Spanish as secondary.

In addition to these, there are a number of seriously endangered and recognised minority languages:

- Aragonese, recognised, but not official, in Aragon.

- Asturian, recognised, but not official, in Asturias.

- Leonese, recognised, but not official, in Castile and León. Spoken in the provinces of León and Zamora.

Spanish itself also has distinct dialects. For example, the Andalusian or Canarian dialects, each with their own subvarieties, some of them being partially closer to the Spanish of the Americas, which they heavily influenced to varying degrees, depending on the region or period and according to different and non-homogeneous migrating or colonisation processes.

Five very localised dialects are of difficult filiation: Fala, a variety mostly ascribed to the Galician-Portuguese group; Cantabrian and Extremaduran, two Astur-Leonese dialects also regarded as Spanish dialects; Eonavian, a dialect between Asturian and Galician, closer to the latter according to several linguists; and Benasquese, a Ribagorçan dialect that was formerly classified as Catalan, later as Aragonese, and which is now often regarded as a transitional language of its own. Asturian and Leonese are closely related to the local Mirandese which is spoken on an adjacent territory but over the border into Portugal. Mirandese is recognised and has some local official status.

With the exception of Basque, which appears to be a language isolate, all of the languages present in mainland Spain are Indo-European languages, specifically Romance languages. Afro-Asiatic languages, such as Arabic (including Ceuta Darija) or Berber (mainly Riffian), are spoken by the Muslim population of Ceuta and Melilla and by recent immigrants (mainly from Morocco and Algeria) elsewhere.

Portuguese and Galician

Linguistic opinion is divided on the matter of the relationship between Galician and Portuguese. Some linguists, such as Lindley Cintra,[9] consider that they are still dialects of a common language, despite differences in phonology and vocabulary. Others, such as Pilar Vázquez Cuesta,[10] argue that they have become separate languages due to major differences in phonetics and vocabulary usage, and, to a lesser extent, morphology and syntax. The official and widespread position (followed by the Galician Language Institute and the Royal Galician Academy) is that Galician and Portuguese should be considered independent languages.

In any case, the respective written standards are noticeably different one from another, partly because of the divergent phonological features and partly due to the usage of Spanish orthographic conventions over the Portuguese ones at the time of Galician standardisation by the early 20th century.

A Galician-Portuguese-based dialect known as Fala is locally spoken in an area sometimes called Valley of Jálama/Xálima, which includes the towns of San Martín de Trevejo (Sa Martin de Trevellu), Eljas (As Elhas) and Valverde del Fresno (Valverdi du Fresnu), in the northwestern corner of Cáceres province, Extremadura.

Portuguese proper is still spoken by local people in three border areas:

- The town of La Alamedilla, in Salamanca province.

- The so-called Cedillo-horn, including Cedillo (in Portuguese Cedilho) and Herrera de Alcántara (in Portuguese Ferreira de Alcântara).

- The town of Olivenza (in Portuguese Olivença), in Badajoz province, and its surrounding territory, which used to be Portuguese until the 19th century and is still claimed by Portugal.

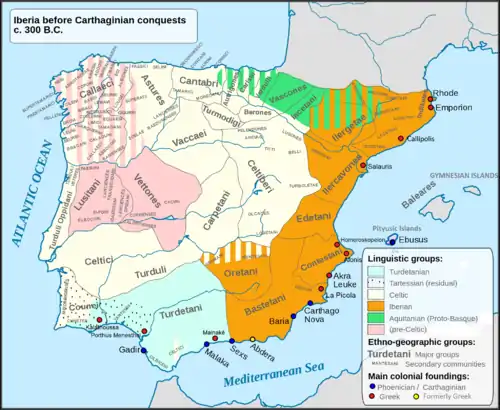

Past languages

In addition to the languages which continue to be spoken in Spain to the present day, other languages which have been spoken within what are now the borders of Spain include:

- Tartessian language

- Iberian language

- Celtic languages

- Lusitanian language

- Punic language

- Latin language

- Guanche language

- Galician-Portuguese

- Gothic language

- Vandalic language

- Frankish language

- Arabic

- Mozarabic languages

- Romani language

Languages that are now chiefly spoken outside Spain but which have roots in Spain are:

- Judeo-Catalan, though the existence of this language has been questioned.

- Judaeo-Spanish (Ladino)[11]

Variants

There are also variants of these languages proper to Spain, either dialect, cants or pidgins:

Further information

- Aragonese (aragonés)

- Astur-Leonese

- Asturian (asturianu, bable)

- Leonese (llionés)

- Mirandese (mirandés, lhéngua mirandesa)

- Extremaduran (estremeñu)

- Cantabrian (cántabru, montañés)

- Basque (euskara)

- Catalan (català), known as Valencian (valencià) in the Valencian Community

- Galician (galego)

- Gascon (Occitan dialect)

- Aranese (aranés)

- Spanish (español)

- Judaeo-Spanish (djudeo-espanyol, judezmo, ladino, sefardi, etc.)

- Dialects of Spanish in Spain

- Sign languages

- Spanish Sign Language (lengua de signos española, LSE).

- Catalan Sign Language (llengua de signes catalana, LSC) and Valencian Sign Language (llengua de signes valenciana, LSV).

- Language politics in Francoist Spain

See also

References

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The term lenguas españolas appears in the Spanish Constitution, referrering to all the languages spoken within Spain (those are Basque, Spanish, Catalan/Valencian, Galician, Asturian, Leonese, etc.).

- Promotora Española de Lingüística - Lengua Española o Castellana Archived 27 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. (Spanish)

- M. Teresa Turell (2001). Multilingualism in Spain: Sociolinguistic and Psycholinguistic Aspects of Linguistic Minority Groups. Multilingual Matters. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-85359-491-5.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Pew Research- Languages spoken at home". Pew Research. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- (in Catalan and Occitan) Llei 35/2010, d'1 d'octubre, de l'occità, aranès a l'Aran

- "els Països Catalans | enciclopèdia.cat". www.enciclopedia.cat. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Lindley Cintra, Luís F. "Nova Proposta de Classificação dos Dialectos Galego-Portugueses" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2006. (469 KB) Boletim de Filologia, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Filológicos, 1971 (in Portuguese).

- Vázquez Cuesta, Pilar «Non son reintegracionista» Archived 8 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine, interview given to La Voz de Galicia on 22 February 2002 (in Galician).

- Jones, Sam (1 August 2017). "Spain honours Ladino language of Jewish exiles". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

External links

- Detailed Ethno-Linguistic map of Pre-Roman Iberia (around 200 BC)

- Detailed linguistic map of Spain

- Languages in Spain - Find out information about the Official languages of Spain.