Nunez River

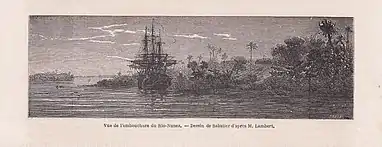

Nunez River or Rio Nuñez (Kakandé) is a river in Guinea with its source in the Futa Jallon highlands. It is also known as the Tinguilinta River, after a village along its upper course.[1]

Geography

Lying between the Kogon River to the north and the Pongo River to the south, the Nunez empties into the Atlantic Ocean at the port town of Kamsar, along the coast of Guinea-Conakry. The river is swollen each year during the rainy season, producing floodplains and inland swamps. These floodplains are inhabited by the Nalu and Baga people.[2] About 40 miles (64 km) inland is the city of Boké; the largest on the river and the chief commercial center of Guinea. Here the river is 100m wide and 1m deep.[3][4]

Upstream from Boké, the shallow river winds through low hills with many series of rapids and small islet clusters to its source, a confluence of several small streams.

Coordinates

| Point | Coordinates (links to map & photo sources) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Source | 10.891°N 14.018°W | |

| Belidima | 11.017°N 14.015°W | |

| Boké | 10.97°N 14.2887°W | |

| Mouth/Port Kamsar | 10.6708°N 14.625°W |

History

Prior to 1840, this river served as a market for Fulbe slave caravans transporting slaves from the Muslim Imamate of Futa Jallon.[5] In 1793 Captain Samuel Gamble of the Sandown was forced to seek protection from enemy war boats and pirates in the mangrove swaps of the Rio Nunez during the French Revolutionary Wars, where vessels were threatened by French privateers along the West African coast. For unknown reasons, he travels to agricultural villages around the commercial centers of Boke and Kacundy. During his journey Gamble records the earliest known description of irrigated rice cultivation in the Rio Nunez region (though earlier accounts exist such Diego Gomes' 15th century record of mangrove rice farming along the Gambia River, detailing his eyewitness account of the process. Records attest to his purchases of both red rice and polished rice from the Rio Nunez's farmers.[6]

In 1849 the river was the site of the Rio Nuñez incident, when a Franco-Belgian squadron of warships fired on Boké, which resulted in loss of inventory by two British traders. The incident was inconclusive.

During the 1870s, this river was a major export point for peanuts, with 5,000 tons per year. In the 1880s, the trade turned to rubber.[7]

Demographics

Speakers of the Rio Nunez languages, Mbulungish and Baga Mboteni, live at the mouth of the Nunez River.[8]

References

- Rouck, J. (1925). Sur les Côtes du Sénégal et de la Guinée. Voyage du Chévigne. Paris. pp. 155–175.

- Coffinières de Nordeck (1886). "Voyage aux pays des Baga et du Rio Nunez par M. le Lieutenant de Vaisseau Coffinières de Nordeck, commandant 'Le Goëland'". Le Tour du Monde: 273–304.

- Fields-Black, Edda L. (2008). Deep roots: rice farmers in West Africa and the African diaspora. Blacks in the diaspora. Indiana University Press. p. 32–34. ISBN 0-253-35219-3.

- National Geospatial-intelligence Agency (2005). Prostar Sailing Directions 2005 West Coast of Europe & Northwest Africa Enroute (9th ed.). ProStar Publications. p. 239. ISBN 1-57785-660-0.

- Thomas, Hugh (1997). The slave trade: the story of the Atlantic slave trade, 1440-1870. A Touchstone Book. Simon and Schuster. p. 683. ISBN 0-684-83565-7.

- Fields, Edda L. (2008). Deep Roots: Rice Farmers in West Africa and the African Diaspora. Indiana University Press. pp. 3-4.

- Martin A. Klein (1998). Slavery and colonial rule in French West Africa. African studies series. 94. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 0-521-59678-5.

- Güldemann, Tom (2018). "Historical linguistics and genealogical language classification in Africa". In Güldemann, Tom (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of Africa. The World of Linguistics series. 11. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 58–444. doi:10.1515/9783110421668-002. ISBN 978-3-11-042606-9.