Nymphaea thermarum

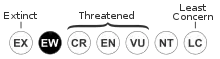

Nymphaea thermarum is the world's smallest water lily. The pads (leaves) of N. thermarum can measure only 1 cm (0.39 in) across, less than 10% the width of the next smallest species in the genus Nymphaea (though they are more usually about 2 cm (0.79 in) or 3 cm (1.2 in)). By comparison, the largest water lily has pads that can reach 3 m (9.8 ft). All wild plants were lost due to destruction of its native habitat, but it was saved from extinction when it was grown from seed at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in 2009.[1][2] In January 2014, a surviving water lily was stolen from the Royal Botanic Gardens.[3]

| Nymphaea thermarum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Order: | Nymphaeales |

| Family: | Nymphaeaceae |

| Genus: | Nymphaea |

| Subgenus: | Nymphaea subg. Brachyceras |

| Species: | N. thermarum |

| Binomial name | |

| Nymphaea thermarum Eb.Fisch. | |

Taxonomy

Nymphaea thermarum was discovered in 1987 by German botanist Eberhard Fischer. The specific epithet, thermarum, refers to the hot spring and temperature that provided its native habitat. There are no common names for the plant, though Kew Gardens is informally calling it "pygmy Rwandan water lily".[4][5]

Description

Nymphaea thermarum forms rosettes 20 to 30 cm (7.9 to 11.8 in) wide, with bright green lily pads growing on short petioles. The very small flowers are white with yellow stamens, with the flowers held upright a few cm above the plant. They can self-pollinate, and after blooming the flower stalk bends so the fruit contacts the mud.[4] The sepals are slightly hairy, and as large as the flower's petals. The plant is a tropical day bloomer displaying protogynous flowering patterns, opening early in the morning on the first day with female floral functioning, closing in early afternoon, and opening on the second day with male functionality.[6] It is in the Nymphaea subgenus Brachyceras, though the leaves are more typical of the subgenus Nymphaea. It apparently does not form tubers. Seeds are large for plants in subgenus Brachyceras.[2]

History

The plant's native habitat was damp mud formed by the overflow of a freshwater hot spring in Mashyuza, Rwanda. It became extinct in the wild about 2008 when local farmers began using the spring for agriculture. The farmers cut off the flow of the spring, which dried up the tiny area—just a few square metres—that was the lily's entire habitat.[4] Before the plants became extinct, Fischer sent some specimens to Bonn Botanic Gardens when he saw that their habitat was so fragile. The plants were kept alive at the gardens, but botanists could not solve the problem of propagating them from seed.[7]

Nymphaea species typically germinate deep under water. N. thermarum seeds are different, needing CO2 in order to germinate. Botanists were unable to germinate any N. thermarum seeds until Carlos Magdalena, at Kew, discovered a solution—only after he was down to his last 20 seeds. By placing the seeds and seedlings into pots of loam surrounded by water of the same level in a 25 °C environment, eight began to flourish and mature within weeks and in November 2009, the waterlilies flowered for the first time.[8] During this time, a rat had eaten one of the last two surviving plants in Germany. With the germination problem solved, Magdalena says that the tiny plants are easy to grow, giving it potential to be grown as a houseplant.[9]

Notes

- Ghosh, Pallab (2010-05-18). "Waterlily saved from extinction". BBC News. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Magdalena, Carlos (November 2009). "The world's tiniest waterlily doesn't grow in water!". Water Gardeners International. 4 (4). Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- "World's smallest waterlily stolen after being dug up". ITV. 2014-01-13. Retrieved 2014-01-13.

- Magdalena, Carlos. "Nymphaea thermarum". Plants & Fungi. Kew Gardens. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Fischer, Eberhard (1993). "Taxonomic results of the BRYOTROP-Expedition to Zaire and Rwanda" (PDF). Tropical Bryology. 8: 13–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- Povilus, RA; Losada, JM; Friedman, WE (2015). "Floral biology and ovule and seed ontogeny of Nymphaea thermarum, a water lily at the brink of extinction with potential as a model system for basal angiosperms". Annals of Botany. 115: 211–226. doi:10.1093/aob/mcu235. PMC 4551091. PMID 25497514.

- McCarthy, Michael (2010-05-19). "Smallest lily saved from extinction". The Independent. London. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- "'Extinct' Waterlily back from the dead" Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Geographic, May 21, 2010.

- Smyth, Chris (2010-05-19). "World's smallest water lily comes from Rwanda to your window sill". The Times. London. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Nymphaea thermarum. |

- Pygmy Rwandan waterlily media from ARKive

- The world's tiniest waterlily doesn't grow in water! by Carlos Magdalena

- Fischer, Eberhard (1993). "Taxonomic results of the BRYOTROP-Expedition to Zaire and Rwanda" (PDF). Tropical Bryology. 8: 13–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- International Plant Names Index