Onager (weapon)

The onager (British /ˈɒnədʒə/, /ˈɒnəɡə/, U.S. /ˈɑnədʒər/[1]) was a Roman torsion powered siege engine. It is commonly depicted as a catapult with a bowl, bucket, or sling at the end of its throwing arm. The onager was first mentioned in AD 353 by Ammianus Marcellinus, who described onagers as the same as a scorpion. The onager is often confused with the later mangonel, a "traction trebuchet" that replaced torsion powered siege engines in the 6th century AD.[2]

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Military of ancient Rome |

|---|

|

|

Etymology

According to two authors of the later Roman Empire who wrote on military affairs, the onager derived its name from the kicking action of the machine that threw stones into the air, as did the hooves of the wild ass, the onager, which was native to the eastern part of the empire.[3]

Design

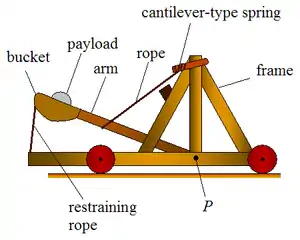

The onager consisted of a large frame placed on the ground to whose front end a vertical frame of solid timber was rigidly fixed. A vertical spoke that passed through a rope bundle fastened to the frame had a cup, bucket, or sling attached which contained a projectile. To fire it, the spoke or arm was forced down, against the tension of twisted ropes or other springs, by a windlass, and then suddenly released. As the sling swung outwards, one end would release, as with a staff-sling, and the projectile would be hurled forward. The arm would then be caught by a padded beam or bed, when it could be winched back again.[4]

By the 4th century, its place as a torsion-powered stone thrower had been taken by the onager, a rather simpler version operating on the same principle. This time, inside a wooden frame that had to be of massive proportions, a single arm was held in a twisted skein of sinew or horsehair. It was loaded by pulling down the arm and placing the missile in the cup at the end, and, on release, the arm flew up to send the missile on its way. The arm was stopped when it hit the necessarily strong crossbeam. Its optimum range was estimated at about 130 metres. Although it might reach much further, by then the force of the impact would have been much reduced. The 2002 reconstruction managed to throw a 26 kg limestone ball 90 yards before the timber of the weapon disintegrated after its second shot.[5]

— Peter Purton

History

The onager was used from the 4th century AD until the 6th century AD. The late-fourth century author Ammianus Marcellinus describes 'onager' as a neologism for scorpions and relates various incidents in which the engines fire both rocks and arrow-shaped missiles.[6] According to Ammianus, the onager was a single-armed torsion engine unlike the twin-armed ballista before it. It needed eight men just to wind down the arm and could not be placed on fortifications because of its great recoil. It had very low mobility and was difficult to aim. Originally it used a bucket or cup to hold the projectile but at some point it was replaced with a sling, which elongated the throwing arm and allowed for a greater range of shot.[7] In 378, the onager was used against the Goths at Adrianople and although it did not cause any casualties, its large stone projectile was incredibly frightening to the Goths. The late-fourth or early-fifth century military writer Vegetius stipulates that a legion ought to field ten onagers, one for each cohort. These he says should be transported fully assembled on ox carts to ensure readiness in case of sudden attack, in which case the onagers could be used for defence immediately. For Vegetius, the onagers were stone throwing machines.[8]

The range of the onager was increased at some point during the Roman imperial period when a sling replaced the cup at the end of the arm. The sling effectively elongated the throwing arm, without adding any notable mass. This allowed the projectile to travel farther in the same amount of time before release, increasing acceleration and release velocity without retarding the angular velocity of the throwing arm or increasing the potential energy in the coil, which would have required the whole structure of the engine to be strengthened.[7]

— Michael S. Fulton

In the late 6th century the Avars brought the Chinese traction trebuchet, otherwise known as the mangonel, to the Mediterranean, where it soon replaced the slower and more complex torsion powered engines.[9]

References

- Oxford English Dictionary.

- Fulton 2016, p. 17.

- Vegetius, De re militari, IV:22; Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History XXIII:4, 4; XXXI:15, 12.

- Denny, Mark "The Physics Teacher" vol 47, p 574-578, December 2009

- Purton 2006, p. 81.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman History, XIX:2 & 7; XX:7; XXIII:4; XXIV: 4; XXXI:15.

- Fulton 2016, p. 10.

- Vegetius, De re militari, IV:22

- Purton, Peter (2009), A History of the Early Medieval Siege c.450–1200, The Boydell Press, p. 364, ISBN 978-1-84383-448-9

Bibliography

- Fulton, Michael S. (2016), Artillery in and around the Latin East

- Purton, Peter (2006), The myth of the mangonel: torsion artillery in the Middle Ages