Opuntia ficus-indica

Opuntia ficus-indica, the prickly pear, is a species of cactus that has long been a domesticated crop plant grown in agricultural economies throughout arid and semiarid parts of the world.[2] Likely having originated in Mexico, O. ficus-indica is the most widespread and most commercially important cactus.[1][2]

| Nopal | |

|---|---|

| |

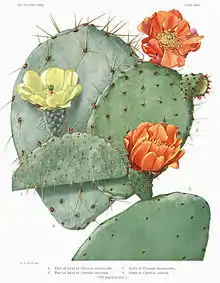

| Illustration by Mary Emily Eaton in The Cactaceae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Cactaceae |

| Genus: | Opuntia |

| Species: | O. ficus-indica |

| Binomial name | |

| Opuntia ficus-indica | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Fig opuntia is grown primarily as a fruit crop, and also for the vegetable nopales and other uses. Cacti are good crops for dry areas because they convert water into biomass efficiently. O. ficus-indica, as the most widespread of the long-domesticated cactuses, is as economically important as maize and blue agave in Mexico. Because Opuntia species hybridize easily, the wild origin of O. ficus-indica is likely to have been in Mexico due to the fact that its close genetic relatives are found in central Mexico.[3]

Names

Most culinary references to the "prickly pear" are referring to this species. The name "tuna" is also used for the fruit of this cactus, and for Opuntia in general; according to Alexander von Humboldt, it was a word of Taino origin taken into the Spanish language around 1500.[4]

Common English names for the plant and its fruit are Indian fig opuntia, Barbary fig, cactus pear, prickly pear, and spineless cactus, among many.[2] In Mexican Spanish, the plant is called nopal, while the fruit is called tuna, names that may be used in American English as culinary terms.

Description

_flowering_at_Secunderabad%252C_AP_W_IMG_6673.jpg.webp)

Opuntia ficus-indica is polyploid, hermaphrodite and autogamous.[5] As Opuntia species grow in semi-arid environments, the main limiting factor in their environment is water. They have developed a number of adaptations to dry conditions, notably succulence.[6]

The perennial shrub Opuntia ficus-indica can grow up to 3–5 m height, with thick, succulent and oblong to spatulate stems called cladodes. It has a water-repellent and sun-reflecting waxy epidermis. Cladodes that are 1–2 years old produce flowers, the fruit's colours ranging from pale green to deep red.[5]

The plants flower in three distinct colours: white, yellow, and red. The flowers first appear in early May through the early summer in the Northern Hemisphere, and the fruits ripen from August through October. The fruits are typically eaten, minus the thick outer skin, after chilling in a refrigerator for a few hours. They have a taste similar to sweet watermelon. The bright red/purple or white/yellowish flesh contains many tiny hard seeds that are usually swallowed, but should be avoided by those who have problems digesting seeds.

Uses

Human consumption

O. ficus-indica are consumed widely as food.[2] The fruits are commercialized in many parts of the world, eaten raw, and have one of the highest concentrations of vitamin C of any fruit.[2] The “leaves” (or cladodes - technically stems) are cooked and eaten as a vegetable known as nopalitos.[2] They are sliced into strips, skinned or unskinned, and fried with eggs and jalapeños, served as a breakfast treat. They have a texture and flavor like string beans. The fruits or leaves can be boiled, used raw, or blended with fruit juice, cooked on a frying pan, and used as a side dish with chicken, or added to tacos. Jams and jellies are produced from the fruit, which resemble strawberries and figs in color and flavor.[2] Mexicans may use Opuntia as an alcoholic drink called colonche.[7]

In Sicily, a prickly pear-flavored liqueur called ficodi is produced, flavored somewhat like a medicinal aperitif. In Malta, a liqueur called bajtra (the Maltese name for prickly pear) is made from this fruit, which can be found growing wild in almost every field. On the island of Saint Helena, the prickly pear also gives its name to locally distilled liqueur, Tungi Spirit.

Fodder

The cattle industry of the Southwest United States has begun to cultivate O. ficus-indica as a fresh source of feed for cattle.[2][8] The cactus is grown both as a feed source and a boundary fence. Cattle are fed the spineless variety of the cactus.[8] The cactus pads are low in dry matter and crude protein, but useful as a supplement in drought conditions. In addition to the food value, the moisture content adequately eliminates watering the cattle during drought.[8] Numerous wildlife species use the prickly pear for food.[8]

Soil erosion prevention

Opuntia ficus-indica are planted in hedges to provide a cheap but effective erosion control in the Mediterranean basin. Under those hedges and adjacent areas soil physical properties, nitrogen and organic matter are considerably improved. Structural stability of the soil is enhanced, runoff and erosion are reduced, while water storage capacity and permeability is enhanced.[9] Prickly pear plantations also have a positive impact on plant growth of other species by improving severe environmental conditions which facilitate colonization and development of herbaceous species.[10]

Opuntia ficus-indica is being advantageously used in Tunisia and Algeria to slow and direct sand movement and enhance the restoration of vegetative cover, minimizing deterioration of built terraces with its deep and strong rooting system.[11]

Other

The plant may be used as an ingredient in adobe to bind and waterproof roofs.[3] O. ficus-indica (as well as other species in Opuntia and Nopalea) is cultivated in nopalries to serve as a host plant for cochineal insects, which produce desirable red and purple dyes,[2] a practice dating to the pre-Columbian era.[12]

Mucilage from prickly pear may work as a natural, non-toxic dispersant for oil spills.[13]

In Mexico there is a semi-commercial pilot plant for biofuel production from opuntia biomass, in operation since 2016.[14]

Cultivation

Distribution

_at_Secunderabad%252C_AP_W_IMG_6674.jpg.webp)

A commercial use for O. ficus-indica is for the large, sweet fruits, called tunas. Areas with significant tuna-growing cultivation include Mexico, the Mediterranean Basin, Middle East and northern Africa.[15] The cactus grows wild and cultivated to heights of 12–16 feet (3.7–4.9 m). In Namibia, O. ficus-indica is a common drought-resistant fodder plant.[16] O. ficus-indica grows in many frost-free areas of the world, including the southern United States.[17]

Prickly pears are a massive weed problem for some parts of Australia, especially southeast Queensland, some inland parts of New South Wales, Victoria, and south-eastern and eastern South Australia.[18][19][20][21]

Growth

The plant is considered an invasive species in northern Africa.[2] Factors that limit the growth of prickly pear are rainfall, soil, atmospheric humidity and temperature.[22] The minimum rainfall requirement is 200mm per year as long as the soils are sandy and deep. The ideal growth conditions when it comes to rainfall are 200–400 millimetres (7.9–15.7 in) per year.[9]

O. ficus-indica is sensitive to lack of oxygen in the root zone, requiring well-drained soils.[9] Opuntia ficus-indica is similar to CAM species which are not salt-tolerant in their root zone where growth may cease under high salt concentration.[9] O. ficus-indica grows usually in regions where relative humidity is above 60% and saturation deficit occurs.[9] O. ficus-indica is absent in regions where there is less than 40% humidity for more than a month.[22] Mean daily temperature required to develop is at least 1.5-2 °C. At −10 to −12 °C, prickly pear growth is inhibited even if it is exposed to these temperatures only for a few minutes. The maximum temperature limit of prickly pear is above 50 °C.[9]

Harvest and preparation

As the fruits of Opuntia ficus-indica are delicate, they need to be carefully harvested by hand. The small spines on the fruits are removed by rubbing them on an abrasive surface or sweeping them through grass. Before consumption, they are peeled.[23]

The pads of the plant (mainly used as fodder) also need to be harvested by hand. The pads are cut with a knife, detaching the pad from the plant in the joint. If Opuntia ficus-indica is cultivated for forage production, spineless cultivars are preferred. However, also wild types of the plants are used as fodder. In these cases, the spines need to be removed from the pads to avoid damage to the animals. Mostly, this is achieved by burning the spines off the pads.[6]

Nutrients and phytochemicals

Opuntia ficus-indica for human and animal consumption is valuable for its water content in an arid environment, containing about 85% water as a water source for wildlife.[6] The seeds contain 3–10% of protein and 6–13% of fatty acids, mainly linoleic acid.[5][24] As the fruit contains vitamin C (containing 25–30 mg per 100g),[5][25] it was once used to mitigate scurvy.[26] Opuntia contains selenium.[27]

The red color of the fruit and juice is due to betalains, (betanin and indicaxanthin).[28] The plant also contains flavonoids, such as quercetin, isorhamnetin,[29] and kaempferol.[30]

Biogeography

DNA analysis indicated O. ficus-indica was domesticated from Opuntia species native to central Mexico.[3] The Codex Mendoza, and other early sources, show Opuntia cladodes, as well as cochineal dye (which needs cultivated Opuntia), in Aztec tribute rolls. The plant spread to many parts of the Americas in pre-Columbian times, and since Columbus, has spread to many parts of the world, especially the Mediterranean, where it has become naturalized.

References

- "Opuntia ficus-indica". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "Opuntia ficus-indica (prickly pear)". CABI. 27 September 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- Griffith, M. P. (2004). "The Origins of an Important Cactus Crop, Opuntia ficus-indica (Cactaceae): New Molecular Evidence". American Journal of Botany. 91 (11): 1915–1921. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.11.1915. PMID 21652337. S2CID 10454390.

- Baron F. H. A. von Humboldt's personal narrative of travels to the equinoctial regions of America tr. 1852 by Ross, Thomasina: "The following are Haytian words, in their real form, which have passed into the Castilian language since the end of the 15th century... Tuna". Quoted in OED 2nd ed.

- Miller, =L. "Opuntia ficus-indica". Ecocrop, FAO. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Mondragón-Jacobo and Pérez-González, C. and S. "Cactus (Opuntia spp.) as Forage". FAO Plant Production and Protection Paper 169. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- "Are prickly pear leaves edible?". 27 February 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Darrell N. Ueckert. "Pricklypear ecology". Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, Texas A&M University. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Le Houérou H. N. (1996). "The role of cacti (Opuntiaspp.) in erosion control, land reclamation, rehabilitation and agricultural development in the Mediterranean Basin". Journal of Arid Environments. 33 (2): 135–159. Bibcode:1996JArEn..33..135L. doi:10.1006/jare.1996.0053.

- Neffar S, Chenchouni H, Beddiar A, Redjel N (2013). "Rehabilitation of Degraded Rangeland in Drylands by Prickly Pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) Plantations: Effect on Soil and Spontaneous Vegetation". Ecologia Balkanica. 5 (2).

- Nefzaoui, A., Ben Salem, H., & Inglese, P. (2001). "Opuntia-A strategic fodder and efficient tool to combat desertification in the Wana region." Cactus, 73–89.

- Kiesling, R. (1999). "Origen, Domesticación y Distribución de Opuntia ficus-indica (Cactaceae)". Journal of the Professional Association for Cactus Development. 3: 50–60.

- University of South Florida. "Cactus a Natural Oil Dispersant". USF News. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- "This Mexican company is making biofuel from cactus plants". The European Sting. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- "Beles". Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. 2003.

- Rothauge, Axel (25 February 2014). "Staying afloat during a drought". The Namibian. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- The Gardeners Dictionary. Opuntia Web (8th ed.). 1768.

- "Opuntia ficus-indica".

- "NSW WeedWise".

- "Atlas of Living Australia".

- "prickly pear - Weed Identification – Brisbane City Council".

- Monjauze, A. & Le Houérou, H. N. (1965). "Le rôle des Opuntia dans l’économie agricole nord africaine." Bulletin de l’Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Agronomie de Tunis, 8–9: 85–164.

- Russel, Felkner; C.E., P. (1987). "The Prickly-pears (Opuntia spp., Cactaceae): A Source of Human and Animal Food in Semiarid Regions". Economic Botany. 41 (3): 443–445. doi:10.1007/bf02859062. S2CID 37653492.

- El Kossori Radia Lamghari; Villaume Christian; El Boustani Essadiq; Sauvaire Yves; Méjean Luc (1998). "Composition of pulp, skin and seeds of prickly pears fruit (Opuntia ficus indica sp.)". Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 52 (3): 263–270. doi:10.1023/A:1008000232406. PMID 9950087. S2CID 44270292.

- Tesoriere L, Butera D, Pintaudi AM, Allegra M, Livrea MA (2004). "Supplementation with cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) fruit decreases oxidative stress in healthy humans: a comparative study with vitamin C". Am J Clin Nutr. 80 (2): 391–5. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.2.391. PMID 15277160.

- Carl Zimmer (December 10, 2013). "Vitamins' Old, Old Edge". The New York Times.

- Bañuelos GS, Fakra SC, Walse SS, Marcus MA, Yang SI, Pickering IJ, Pilon-Smits EA, Freeman JL (January 2011). "Selenium Accumulation, Distribution, and Speciation in Spineless Prickly Pear Cactus: a Drought- and Salt-Tolerant, Selenium-Enriched Nutraceutical Fruit Crop for Biofortified Foods". Plant Physiology. 155 (1): 315–327. doi:10.1104/pp.110.162867. PMC 3075757. PMID 21059825.

- Butera D, Tesoriere L, Di Gaudio F, et al. (November 2002). "Antioxidant activities of sicilian prickly pear (Opuntia ficus indica) fruit extracts and reducing properties of its betalains: betanin and indicaxanthin". J. Agric. Food Chem. 50 (23): 6895–901. doi:10.1021/jf025696p. hdl:10447/107910. PMID 12405794.

- Dok-Go Hyang; Heun Lee Kwang; Ja Kim Hyoung; Ha Lee Eun; Lee Jiyong; Seon Song Yun; Lee Yong-Ha; Jin Changbae; Sup Lee Yong; Cho Jungsook (2003). "Neuroprotective effects of antioxidative flavonoids, quercetin, (+)-dihydroquercetin, and quercetin 3-methyl ether, isolated from Opuntia ficus-indica var. saboten". Brain Research. 965 (1–2): 130–136. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(02)04150-1. PMID 12591129. S2CID 8345824.

- Kuti Joseph O. (2004). "Antioxidant compounds from four Opuntia cactus pear fruit varieties". Food Chemistry. 85 (4): 527–533. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00184-5.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Opuntia ficus-indica. |