Ozymandias

"Ozymandias" (/ˌɒziˈmændiəs/ oz-ee-MAN-dee-əs)[1] is the title of a sonnet written by the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822). It was first published in the 11 January 1818 issue of The Examiner[2] of London. The poem was included the following year in Shelley's collection Rosalind and Helen, A Modern Eclogue; with Other Poems,[3] and in a posthumous compilation of his poems published in 1826.[4]

| by Percy Bysshe Shelley | |

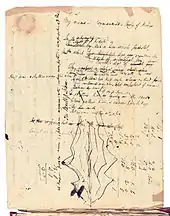

Shelley's "Ozymandias" in The Examiner | |

| First published in | 11 January 1818 |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | Modern English |

| Form | Sonnet |

| Meter | Loose iambic pentameter |

| Rhyme scheme | ABABA CDCEDEFEF |

| Publisher | The Examiner |

| Read online | "Ozymandias (Shelley)" at Wikisource |

Shelley wrote the poem in friendly competition with his friend and fellow poet Horace Smith (1779–1849), who also wrote a sonnet on the same topic with the same title. The poem explores the fate of history and the ravages of time: even the greatest men and the empires they forge are impermanent, their legacies fated to decay into oblivion.

Origin

In antiquity, Ozymandias (Ὀσυμανδύας) was a Greek name for the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II.

Shelley began writing his poem in 1817, soon after the British Museum's announcement that they had acquired a large fragment of a statue of Ramesses II from the 13th century BCE; some scholars believe Shelley was inspired by the acquisition. The 7.25-short-ton (6.58 t; 6,580 kg) fragment of the statue's head and torso had been removed in 1816 from the mortuary temple of Ramesses (the Ramesseum) at Thebes by the Italian adventurer Giovanni Battista Belzoni. It had been expected to arrive in London in 1818, but did not arrive until 1821.[5][6]

Writing, publication and text

Publication history

The banker and political writer Horace Smith spent the Christmas season of 1817–1818 with Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Shelley. At this time, members of the Shelleys' literary circle would sometimes challenge each other to write competing sonnets on a common subject: Shelley, John Keats and Leigh Hunt wrote competing sonnets about the Nile around the same time. Shelley and Smith both chose a passage from the writings of the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, which described a massive Egyptian statue and quoted its inscription: "King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work." In Shelley's poem, Diodorus becomes "a traveller from an antique land."[7]

The poem was printed in The Examiner,[2] a weekly paper published by Leigh's brother John Hunt in London. Hunt admired Shelley's poetry and many of his other works, such as The Revolt of Islam, were published in The Examiner.[8]

Shelley's poem was published on 11 January 1818 under the pen name Glirastes.[9] It appeared on page 24 in the yearly collection, under Original Poetry. Shelley's poem was later republished under the title "Sonnet. Ozymandias" in his 1819 collection Rosalind and Helen, A Modern Eclogue; with Other Poems by Charles and James Ollier[3] and in the 1826 Miscellaneous and Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley by William Benbow, both in London.[4]

Text

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.— Percy Shelley's "Ozymandias"[4]

Analysis and interpretation

Form

Shelley's "Ozymandias" is a sonnet, written in iambic pentameter, but with an atypical rhyme scheme (ABABA CDCEDEFEF) when compared to other English-language Petrarchan sonnets, and without the characteristic octave-and-sestet structure.

Hubris

A central theme of the "Ozymandias" poems is the inevitable decline of rulers with their pretensions to greatness.[10] The name "Ozymandias" is a rendering in Greek of a part of Ramesses II's throne name, User-maat-re Step-en-re. The poems paraphrase the inscription on the base of the statue, given by Diodorus Siculus in his Bibliotheca historica as:

King of Kings am I, Ozymandias. If anyone would know how great I am and where I lie, let him surpass one of my works.[11][12][13]

Although the poems were written and published before the statue arrived in Britain,[6] they may have been inspired by the impending arrival in London in 1821 of a colossal statue of Ramesses II, acquired for the British Museum by the Italian adventurer Giovanni Battista Belzoni in 1816.[14] The statue's repute in Western Europe preceded its actual arrival in Britain, and Napoleon, who at the time of the two poems was imprisoned on St Helena (although the impact of his own rise and fall was still fresh), had previously made an unsuccessful attempt to acquire it for France.

In pop culture

- In the movie Alien: Covenant (2017) the poem is uttered by David the Cyborg as he rains destruction on the alien race.

- In the AMC drama Breaking Bad, the 14th episode of season 5 is titled "Ozymandias." The episode's title alludes to the collapse of protagonist Walter White's drug empire.

- In the graphic novel Watchmen, as well as in its film and television adaptations, "Ozymandias" is the superhero alias of Adrian Veidt. The name can be understood as a reference to Veidt's hubris, as well as to the fact that in the graphic novel, Veidt goes to great lengths to establish world peace, only for the ending to indicate that this peace is fleeting and will collapse in the end.

- Joanna Newsom's song "Sapokanikan" begins with the lines, "The cause is Ozymandian / The map of Sapokanikan / Is sanded and bevelled / The land lone and levelled / By some unrecorded and powerful hand."

See also

- Hubris

- "Eighteen Hundred and Eleven", a poem by Anna Laetitia Barbauld which also imagines future tourists visiting a ruined London

References

- Wells, John C. (1990). "s.v. Ozymandias". Longman pronunciation dictionary. Harrow: Longman. p. 508. ISBN 0-582-05383-8. The four-syllable pronunciation is used by Shelley to fit the poem's meter.

- Glirastes (1818), "Original Poetry. Ozymandias", The Examiner, A Sunday Paper, on politics, domestic economy and theatricals for the year 1818, London: John Hunt, p. 24

- Reprinted in Shelley, Percy Bysshe (1876). Rosalind and Helen - Edited, with notes by H. Buxton Forman, and printed for private distribution. London: Hollinger. p. 72.

- Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Ozymandias" in Miscellaneous and Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley (London: W. Benbow, 1826), 100.

- British Museum. Colossal bust of Ramesses II, 'The Younger Memnon'. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- Chaney, Edward (2006). "Egypt in England and America: The Cultural Memorials of Religion, Royalty and Revolution". In Ascari, Maurizio; Corrado, Adriana (eds.). Sites of Exchange: European Crossroads and Faultlines. Internationale Forschungen zur Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaft. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi. pp. 39–74. ISBN 9042020156.

- Siculus, Diodorus. Bibliotheca Historica. 1.47.4.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Graham, Walter (1925), "Shelley's Debt to Leigh Hunt and the Examiner", PMLA, 40 (1): 185–192, doi:10.2307/457275, JSTOR 457275

- https://www.nypl.org/blog/2018/07/06/romantic-interests-ozymandias-shelley-dormouse

- "MacEachen, Dougald B. CliffsNotes on Shelley's Poems. 18 July 2011". Cliffsnotes.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- See footnote 10 at the following source, for reference to the Loeb Classical Library translation of this inscription, by C.H. Oldfather: http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poems/ozymandias, accessed 12 April 2014.

- See section/verse 1.47.4 at the following presentation of the 1933 version of the Loeb Classics translation, which also matches the translation appearing here: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/1C*.html, accessed 12 April 2014.

- For the original Greek, see: Diodorus Siculus. "1.47.4". Bibliotheca Historica (in Greek). 1–2. Immanel Bekker. Ludwig Dindorf. Friedrich Vogel. In aedibus B. G. Teubneri. At the Perseus Project.

- "Colossal bust of Ramesses II, the 'Younger Memnon'" Archived 2 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. British Museum. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

Bibliography

- Rodenbeck, John (2004). "Travelers from an Antique Land: Shelley's Inspiration for 'Ozymandias'". Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, no. 24 ("Archeology of Literature: Tracing the Old in the New"), 2004, pp. 121–148.

- Johnstone Parr (1957). "Shelley's 'Ozymandias'". Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. VI (1957).

- Waith, Eugene M. (1995). "Ozymandias: Shelley, Horace Smith, and Denon". Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 44, (1995), pp. 22–28.

- Richmond, H. M. (1962). "Ozymandias and the Travelers". Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 11, (Winter, 1962), pp. 65–71.

- Bequette, M. K. (1977). "Shelley and Smith: Two Sonnets on Ozymandias". Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 26, (1977), pp. 29–31.

- Freedman, William (1986). "Postponement and Perspectives in Shelley's 'Ozymandias'". Studies in Romanticism, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Spring, 1986), pp. 63–73.

- Edgecombe, R. S. (2000). "Displaced Christian Images in Shelley's 'Ozymandias'". Keats Shelley Review, 14 (2000), 95–99.

- Sng, Zachary (1998). "The Construction of Lyric Subjectivity in Shelley's 'Ozymandias'". Studies in Romanticism, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Summer, 1998), pp. 217–233.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Audiorecording of "Ozymandias" by the BBC.

- Ozymandias Summary, Themes, and Analysis

- Ozymandias - Annotated text + analyses aligned to Common Core Standards

Ozymandias public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Ozymandias public domain audiobook at LibriVox- "Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822), "Ozymandias"". Representative Poetry Online. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

(text of poem with notes)