Palazzina Appiani

Palazzina Appiani is a historical building located in Milan, northern Italy.[1] It was built as the entrance hall of the arena at the beginning of the 19th century by the French,[2] who occupied Milan in 1796. Its original function was to be the official gallery and guest residence to host Napoleon's family during his public appearances.[2] It is located in Parco Sempione, the biggest park in the city, which also comprises the Sforza Castle and the Arch of Peace. Adjacent to the Arena Civica, the Palazzina is now entrusted to FAI – Fondo Ambiente Italiano.[1]

| Palazzina Appiani | |

|---|---|

Palazzina Appiani | |

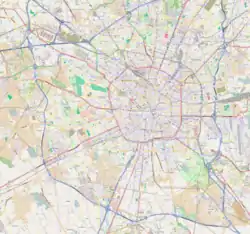

| Milan in Italy | |

| |

Palazzina Appiani Location within Milan | |

| Coordinates | 45°28′33″N 9°10′45″E |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Comune of Milan |

| Controlled by | FAI (Fondo Ambiente Italiano) |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Restored by FAI (2009–2013) |

| Website | https://www.fondoambiente.it/luoghi/palazzina-appiani |

| Site history | |

| Built | 18th century |

| In use | Until 1862 |

| Events | Available for private events |

History

Origins

The building was designed for Napoleon, his family and court to watch the games in the arena below, allowing them to watch the performances privately, from a preferential position. The building project also included the Arena Civica, and, at the center of the space, the Sforza Castle, which was meant to play host to the building of power: the central headquarters of Napoleon's government. Just like other places dedicated to art and culture, the building accommodated a theater on each side, but the original project's completion was estimated to take around ten years and cost approximately six million Milanese Lira ( the contemporary currency). Owing to the exceptionally high cost, it was deemed too expensive and abandoned.[3]

Palazzina Appiani is one of the few surviving buildings that evidences the ambitious urban plans conceived by the French Emperor. Napoleon's plan should have been carried out by the Italian architect Giovanni Antolini, but due to its excessive cost, it was never realized. Napoleon's objective was to make Milan as important as Paris, the capital of his Empire.[4] He was trying to accelerate the growth of the city with some architectural projects, including the one for the Palazzina. The project of the Palazzina was included in what Napoleon wanted to call the "Bonaparte's Forum", thought of as the new political center of the city.[4] This was to be designed following Neoclassical doctrine, as it was associated with the new liberal political movements of the time, like that of the Emperor, as opposed to Rococo and Baroque, which were considered to be the symbol of the absolutist monarchies.

.jpg.webp)

The Palazzina was not only conceived as the palace where Napoleon's family could watch the competition in the Arena Civica, but also as the building from which he and his court could host his public appearances. [4]

The Project by Giovanni Antolini

Napoleon's project was initially entrusted to Giovanni Antolini in 1801.[5] The original plan provided a large circular-based open space, 570 meters in diameter, broken by two wide crossings for carriages and with a navigable canal linked to the main canal network that ran around the city's inner boundary. This project was then rejected by the French government because it was too expensive and therefore abandoned.[3] These initial plans provided an inspiration for the actual final project.

The Project by Luigi Canonica

Antolini's initial project was redesigned by Luigi Canonica, one of the main exponents of the Italian Neoclassical movement.[6] In 1797 Canonica replaced Piermarini, his former teacher, in the role of national architect of the Cisalpine Republic, which was instituted by Napoleon Bonaparte during the end of the XVIII century.[7]

Antolini's wooden amphitheater project was the started point for Luigi Canonica who decided to scale back the project to include just the Sforza Castle, placing a large open square in front of it, which echoes Antolini's in its curved lines and shapes. While the open space behind the castle remained substantially unchanged, the Arch of Peace, which stands on the other side, was designed by the marquis Luigi Cagnola in 1806.[1]

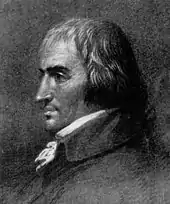

Andrea Appiani's contribution

Andrea Appiani was Napoleon's official Italian painter and in 1802 was appointed commissioner of the Cisalpine Republic's entertainment. To celebrate the Day of the Republic, on 26 June 1803, he designed a wooden circus inspired by Roman Times, which then represented the main inspiration for Luigi Canonica's work on the Palazzina. During 1803 Canonica reconsidered Andrea Appiani's short-lived plan for the Bonaparte Forum, intending to create a location for official events. Napoleon officially approved the project in 1805 and construction work began in 1806, using the materials gathered from the destruction of the Sforza Castle fortifications. The blueprints comprised a large elliptical structure of 238 meters in length and 116 meters in width, covered by a row of shrubbery and with a capacity of 30,000 people.[6]

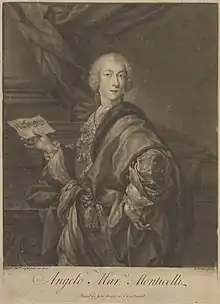

Angelo Monticelli's contribution

The Hall's ceiling is richly decorated with vegetable spirals above the frieze, all realized between 1807 and 1818 by Angelo Monticelli, considered the pupil of Appiani.

Monticelli was a very productive painter at the time, engaged in the great neoclassical construction sites within Milan and outside the city. A main influence that he chose to reference were the commemorative friezes of the Republican and Imperial Rome, especially the one of the Ara Pacis Augustae, to which he added the knowledge of the frieze of the Parthenon. The artist incorporated the features and postures of characters inspired by well-known ancient sculptures, paintings, and drawings by artists of the Renaissance and Neoclassicism, such as Michelangelo and Canova, giving to the frieze a style typical of the Roman architecture. These references and inspirations suggest that Monticelli had a very wide cultural background. The frieze incorporated the pictorial rendering of the effect of sculpted bas-relief, obtained with skillful use of chiaroscuro with the addition of light-and-shade.

Expo 1906

For the World's fair of 1906, commemorating the construction of the Simplon tunnel, the facade of Palazzina Appiani was temporarily modified for the occasion with a monumental staircase in order to align it with the temporary stands built for the event. After the end of the exposition, the decorative elements were removed and the building was brought back to its original neoclassical style.[3]

XXI century

In 2007 the Palazzina hosted the Polish artist Pawel Althamer's first major exhibition in Italy ''One of many'' focused on the theme of portraits.[8]

The municipality of Milan permitted the Palazzina Appiani to become an FAI property in 2009, functioning as the headquarters of the FAI Delegation for Milan and as the Regional Presidency of FAI Lombardy. In January 2015 an agreement was stipulated between FAI and the Commune granting the concession of the property for a period of ten years. Palazzina Appiani still represents the symbol of Neoclassical style and is one of the few testimonies of Napoleon's plans in Italy. Palazzina Appiani is also used as a location for various types of events, such as meetings, presentations, weddings, gala dinners, and parties because of the large surface area it provides.[9]

In 2018 Palazzina Appiani appeared in Wikimedia's contest "wiki loves monuments Italia 2018". The building is also recognized by the Italian body "Residenze d'epoca" which gives Palazzina Appiani the "Corona d'argento" after a preliminary assessment of eligibility.

The mosaic flooring has been damaged during the years, and in 2020 the FAI, with the help of private donors, is working on renovating it, together with all the other damaged parts of the building.

Style and architecture

Palazzina Appiani has two floors with a rectangular plan. Its exterior resembles other eighteenth-century villas designed by Piermarini. The Palazzina has five arched porch surmounted by a baluster linked to the low-built wall belt. The external side, which faces the Arena, recalls the Imperial Rome with a lodge of eight pink granite Corinthian columns and honor bleachers.

The building comprises wide internal stairs and a contiguous room where the queen used to wait during the intervals in shows.

The mosaic shows alterations of the original and has recently been subjected to a major conservative restoration on its entire surface where grafts of new plugs and mortars to fill the damaged plugs are visible

The Hall of Honor

The Hall of Honor, which is located on the first floor, has access to the loggia that faces the Arena Civica.[10] At the entrance of the Hall of Honor there are paved mosaics with classic motif, rosettes, meandering bands, and layered surfaces, designed by Luigi Canonica and inspired by strict Classicalism. At the central entrance, which was designed by the house of C. Fabricio as evidenced by the signature, the central rosette, which once decorated the entrance, was replaced in 1928 with the coat of arms of Milan, which was granted jurisdiction over the entire arena in 1870.[3] The creators' names of the mosaics are readable between the mosaic tiles, including the firms Fabricio and Fantini. The latter also worked on other buildings close to the Palazzina in the 1830s. The mosaic shows differences from the original project and it has recently been subjected to a major conservative restoration on its entire surface where grafts of new plugs and mortars to fill the damaged plugs are visible.

On the upper floor in the main salon, there are two large chandeliers made of gilded bronze and Bohemian crystals. They hang from the vault that is painted with medallions held up by spirits, acanthus flowers, and panoplies. The Hall of Honour shows a continuous chiaroscuro painted frieze personally requested by Napoleon, which was designed by Andrea Appiani and was inspired by the pages of Roman Antiquities by Dionysius of Halicarnassus. It represents a solemn votive procession that recalls the final triumph of the Napoleonic era.[3]

Studies carried out by FAI confirm that even if the frieze was actually designed by Appiani, it was eventually completed by one of the artists working for him in his workshop, Angelo Monticelli. No official documents were found proving the presence of Andrea Appiani in the site, but the style of the frieze is the same as other works on which he was working in that period of time.[3]

The Frieze by Monticelli

The frieze is reportedly inspired by the work "Roman antiquities" written by Dionysius of Halicarnassus in the I° century b.c. under the emperor August. The work is about a ritual parade, from the capitol to the forum and maximum cycle. It frames the whole ceiling, showing a unique parade divided into different scenes, one for each wall, allowing a continuous narration.

The artist not only made references to Rome and the Emperor but also to Greek mythology. One of the subjects is the Panathenaic Games, which was the most important festival in the Athenian calendar and was composed of games and ritual activities hosted in honor of the goddess Athena. The festival culminated in a solemn procession in which young girls carried the goddess's robe to the Pantheon, the temple dedicated to her on the Acropolis. The Panathenaic Games were symbols of unity for all Athenian citizens from a political point of view and so the artist, through this representation wanted to exalt Napoleon's greatness as well as his political power.

On the long side of this frieze, from the left, are shown the magistrates, wearing a laurel wreath and having a roll in their hand, then the Litters, bearers of the littoral Fasces, that anticipate in the procession the Victimils, wearing an apron which covered them from the belly to the knees. They brought sacrificial animals (as ox, bull, goat, and boar) to kill them in honor of the Gods. These characters are followed by characters bearing beggar offerings, candelabras, baskets, and birds in a cage.[11]

The next figures in the procession are àuguri, priests who had to interpret Gods' will by watching the birds flying and inspecting their internal organs. These are followed by bearers with incense and camilli (boys, sons of aristocrats), identified by their short tunic, who assisted bearing incense and jugs. In the middle of the ritual parade, is the celebrant, shown as a commander with embers. The whole procession is symmetric, and terminates on the long side with camilli and musicians with flutes, horns, and lyre. On the right are shown bearers of incense and offerings of gold and silver. These are followed by vestals (female figures), bearing offerings and garlands.

The short sides in front of the stairs are decorated with a chariot bringing shields and trophies, and sculptures of gods, such as Neptune and Mercury. On the opposite side, on the stairs, is shown a chariot procession with Jupiter,[12] pulled by lions and feline animals, followed by other wagons carrying models of temples and altars. On the other long side, on the right, are represented satyrs or fauns, mythological figures with goat ears, adorned with vine leaves, which are related to wine and dance. Then the athletic competitions that follow the ceremony.

From the left, the frieze depicts jockeys on their chariots and horses racing. On the right, a lion and statue Cybele venerated as "Great Mother Idea", the depiction of the goddess-mother, recognizable for her crown, during the festivity celebrated in Rome between 4 and 10 April in her honor. She bears a symbol for the abundance of wealth on the earth.

The short column between the human figures was the point in which athletes had to turn and which wreaths of laurel for the winners were put on. Fighters' portraits as naked figures are following. Then the podium and discobolus. At the end of the parade, there are horses, as at the beginning, since the parade has a circular narration

The Frieze has undergone some restoration over the years. In 2013 it was decided to use a completely different technique from the original to replenish the missing traits of Monticelli's frieze, which disappeared due to water infiltration. The aim of the new reconstruction was to make the restored areas recognizable without compromising the continuity of the narrative.

The Pulvinare

The Pulvinare, or Real Lodge, was completed in 1813 with the Porta Trionfale, conceived as a lobby to host the royal family. The Arena's Pulvinare was intended to be the setting for Napoleon's display of power: the Emperor's seat occupied the central position of the building itself and of the Arena in general, in order that he could be seen by everyone in the complex. Eight enormous pink-granite monolithic columns of the inner facade, four of which come from the Milanese convent Sant'Agostino, end in elegant capitals in Eastern Corinthian style. The columns support one of the sides of the spacious open gallery, covered by a lowered semicircular vault with a square pattern. The stage of honour's balustrade only runs around its side and ends in sculpted winged lions. The central part of it was open and hung over the stands so that everyone could see the Emperor.[13] It unusually has two fronts. The main facade facing Parco Sempione recalls the strict lines of the Italian architect Piermarini with its faithful classical style. The Palazzina, mounted on the South-West side of the tribune, was inspired by an idea in Tazzini. The five closely-spaced arches that mark the covered entrance for carriages, which are accompanied by five windows on the upper balcony, are characteristic architectural features of the prominent central building. The side facing the Arena is the Pulvinare itself. Since no official documents have been provided for the interpretation of the name of this building scholars have two main suppositions on the origin of the name. It could derive from the Latin termpulvinus, or cushion: in Ancient Rome it was the platform where images of the Gods were placed during religious festivals so that they could watch over feasts and games in their honor. In extension, the name was given to the imperial platform and above all to the stage in circuses and amphitheatre from which the Emperor would watch the games.[13] Another interpretation comes from the same Latin term which can also stand for the bed on which Romans used to lay during ceremonies, in this case, the name is intended to celebrate the importance of Napoleon.

Surrounding Buildings

The importance of unity

The project that Napoleon was meant to realize was not thought of as an aggregate of several buildings but was meant to be considered as a whole. The Palazzina acquires value only if it is related to the surrounding buildings which dated back to Napoleon's Empire. The concept of unity became the symbol of a new-found Peace, an idea that Napoleon conveyed in Italy after defeating the Austrian power.

The Arena

In 1801, after the fall of the Austrians, the walls which surrounded the city were demolished and in 1803, Canonica took up the idea of an ephemeral apparatus of a wooden circus designed by Andrea Appiani, with the intention of creating a place where official demonstrations could take place. Napoleon approved it in 1805.[6]

The arena has an ellipsoidal shape with thick rough-looking walls, made by demolition materials, and is crowned by a green belt with trees. Frequented and with a proposal of exclusive games, it will become the beating and festive center of the new Napoleonic Milan.

As the Roman arenas, the Arena could be flooded by overflowing the Euripo, a canal running along the perimeter of the structure bringing water from the Martesana, one of the main canals of the city. In the middle of the lagoon temporary structures could be erected and taken down as necessary, to create scenographic effects during the shows. The flooding of the Arena allowed sea battles with model boats, which fired cannonballs and sank each other with the help of complex hidden machines.

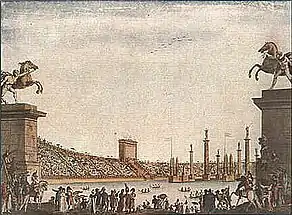

An engraving made in 1807 presented a caricature of a nautical show that took place in the Arena; the crowd crammed together waiting to enter, the audience packed in the stands to watch the sea battle.[14]

As Napoleon aimed to restore the ancient roman lifestyle in the city, the Arena often hosted historical races, Venetian gondola's Regattas,[15] shows re-staging the gladiatorial games, firework displays, and theatre performances.[4] The Arena became a central cultural focus for the new Napoleonic Milan.[6] The new lifestyle, brought to the city by the French occupants, was enjoyed by the population, as shown in paintings and engravings of the time, portraying the crowds standing outside or sitting inside the Arena. The surrounding area became one of the centers of 19th century Milan; whilst Piazza Duomo became one of the symbols of a religious power perceived as outdated and stale. The Arena is made up of various architectural structures: Porta Trionfale, the Pulvinare, the Carceri, the Porta Libitinaria, and the Arena itself.[13]

Porta Trionfale

Porta Trionfale was completed in 1813. It is a single-furnace coffered triumphal arch, made of Baveno granite. It presents a Doric order pronaos, with four Doric-style grooved columns, two for each side, surmounted by a frieze and by the pediment. The frieze decoration conforms to this architectural style by alternating Triglyphs, metopes, and weapons. The tympanum sculptures of Gaetano Monti, a pupil of Antonio Canova, depicts the goddess Victory crowning the winners. The pediment was completed by a mansard on top of it, which gives the triumphal arch an appearance of precision and majesty.[13]

The Carceri

The Carceri were finished between 1824 and 1826 by Giacomo Tazzini, with the project elaborated by Luigi Canonica. The building of the Carceri is composed of ten arches shaped gates through which horses and chariots entered the circus or arenas. The shape reminds the main door, Porta Trionfale and all the ten doors are inward. The Carceri emanates a feeling of imposing solidity as well, refined by the two turrets raised up on each side.[13]

Porta Libitinaria

Porta Libitinaria was completed in 1824 and was based on the architecture of Ancient Rome arenas. In the Roman world, the libitini were the gravediggers who transported gladiator's corpses out of the arena.[13]

Gallery

Palazzina Appiani's main entrance

Palazzina Appiani's main entrance Palazzina Appiani's round arches

Palazzina Appiani's round arches Palazzina Appiani's main room photographed from the side door

Palazzina Appiani's main room photographed from the side door View of Palazzina Appiani from the garden

View of Palazzina Appiani from the garden Main source for Palazzina Appiani's Frieze's iconography

Main source for Palazzina Appiani's Frieze's iconography Facade of Palazzina Appiani from Parco Sempione

Facade of Palazzina Appiani from Parco Sempione Details of the facade

Details of the facade Porch of Palazzina Appiani

Porch of Palazzina Appiani Porch of Palazzina Appiani with view on Parco Sempione

Porch of Palazzina Appiani with view on Parco Sempione

See also

References

- "Discover Palazzina Appiani". www.fondoambiente.it. Fondo Ambiente Italiano. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Abernethy, Celia (24 September 2018). "Napoléon's Lost Vision of Milan | Milanostyle". MilanoStyle. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- "Palazzina Appiani" (PDF). FAI (Fondo Ambiente Italiano) (in Italian).

- "Palazzina Appiani: la dimora di Napoleone ieri e oggi – FOTO e VIDEO". Panorama (in Italian). 17 October 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Granuzzo, Elena. "Gaetano Pinali, Luigi Cagnola, Giovanni Antonio Antolini, 1800-1842: Spigolature D'archivio". Arte Lombarda (in Italian). 145: 106–13 – via JSTOR.

- Maurizio, Zucchi (2019). La Soria di Milano in 501 domande e risposte. Italy: Newton Compton. ISBN 9788822736284.

- Lunardini, Matteo (2013). I Fantasmi dll'Arena. Milieu. p. 2.

- Calò, Giorgia; Scudero, Domenico (2009). Moda e Arte: dal Decadentismo all'Ipermoderno. Gangemi Editore spa. p. 257. ISBN 8849217064.

- "PALAZZINA APPIANI | Bene FAI". www.fondoambiente.it (in Italian). Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- "Palazzina Appiani". Art Bonus. Ente Beneficiario Delle Erogazioni Liberali. 16 January 2020 – via Art Bonus, which hosts the data curated by the Ente Beneficiario Delle Erogazioni Liberali.

- Ferrario, Giulio (1832). Il *costume antico e moderno, ovvero Storia del governo, della milizia, della religione, delle arti, scienze ed usanze di tutti i popoli antichi e moderni provata coi monumenti dell'antichita e rappresentata con analoghi disegni. Sapienza - Università di Roma: Alessandro Fontana.

- "Palazzina Appiani". Palazzina Appiani.

- "L'Architettura dell'Arena" (PDF). FAI (Fondo Ambiente Italiano) (in Italian).

- Pedrazzini, Marco (11 December 2011). "Arena, le curiosità d'archivio". Corriere Della Sera (in Italian).

- Dell'Acqua, Marco; Pavone, Giuliano (2011). 101 perché sulla storia di Milano che non puoi non sapere. Italy: Newton Compton. ISBN 9788854184404.

Bibliography

- Dina Lucia Borromeo Il libro del FAI, Skira (20 November 2013) ASIN 8857221202, ISBN 978-8857221205

- Ciardi, Roberto Paolo. "Andrea Appiani 'Commissario per Le Arti Belle'." Prospettiva, no. 33/36, 1983