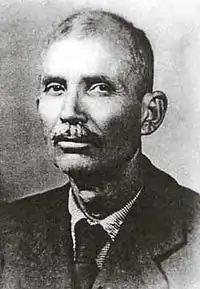

Panko Brashnarov

Panko Brashnarov (Bulgarian: Панко Брашнаров, Macedonian: Панко Брашнар, Panko Brašnar) (1883, Veles, Kosovo Vilayet, Ottoman Empire – 1951, Goli Otok, Yugoslavia) was a revolutionary and member of the left wing of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO) and IMRO (United) later. As with many other IMARO members of the time, historians from North Macedonia consider him an ethnic Macedonian,[1] whereas historians in Bulgaria consider him a Bulgarian.[2] However such Macedonian activists,[3] who came from the IMARO[4] and the IMRO (United) never managed to get rid of their strong pro-Bulgarian bias,[5][6] and continued to see themselves as Bulgarians, even in Communist Yugoslavia.[7]

He was born in Veles (then known by the name Köprülü) in the Kosovo Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire (present-day North Macedonia) where he graduated from Bulgarian Exarchate's school. Brashnarov graduated from the Bulgarian pedagogical school in Skopje.[8] In 1903 he took part in the Ilinden Uprising. In 1908 he joined the People's Federative Party (Bulgarian Section). In 1903-1913 Brashnarov worked as Bulgarian teacher. In 1914-1915 he completed a two-year higher educational course in Plovdiv. He was mobilized in the Bulgarian army during the First World War and participated in the battles of Doiran. After Bulgaria lost the war, the Bulgarian occupation of Vardar Macedonia ended and Brashnarov remained in the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In 1919, he joined the Yugoslav Communist Party. In 1925 in Vienna, Brashnarov was elected as one of the leaders of Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (United).[9] Because of his political convictions, he was sentenced to seven years in prison in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In report the Vienna newspaper Arbeiter Zeitung from 2 July 1929 stated that the 50-year-old Macedonian Bulgarian Panko Brashnarov, was imprisoned in Maribor.[10] After his release in 1936 he remained politically passive.

When Bulgaria occupied and later annexed Vardar Banovina in 1941, he was one of the founders of the Bulgarian Action Committees[11] Until 1943 Brashnarov worked again as a Bulgarian teacher. Till then there was no real communist resistance in Vardar Macedonia, but in the middle of 1943 it became obvious that Germany and Bulgaria would be defeated.[12] In the same year Brashnarov became politically active again and joined the Yugoslav Communist partizan's movement there fighting against the Axis Powers. At that time the Yugoslav communists recognized a separate Macedonian nationality to stop the fears of the local population that they would continue the former Yugoslav policy of forced serbianization, but they didn't support the view that the Macedonian Slavs are Bulgarians, because that meant in practice, the area should remain part of the Bulgaria after the war.[13] On 2 August 1944, the Antifascist assembly of the national liberation of Macedonia took place at the St. Prohor Pčinjski monastery. Brashnarov served as the first speaker.[14] The modern Macedonian state was officially proclaimed as a federal state within Josip Broz Tito's Yugoslavia, receiving recognition from the Allies in 1945.

The new Macedonian authorities had a primary goal to de-Bulgarize the Macedonian Slavs and to create a separate Macedonian consciousness that would inspire identification with Yugoslavia.[13] From the start of the new Yugoslavia, these authorities organised frequent purges and trials of Macedonian communists and non-party people were charged with autonomist deviation. Many of the former left-wing IMRO government officials were purged from their positions, then isolated, arrested, imprisoned or executed on various (in many cases fabricated) charges including pro-Bulgarian leanings, demands for greater or complete independence of Yugoslav Macedonia, collaboration with the Cominform after the Tito-Stalin split in 1948, forming of conspirative political groups or organisations, demands for greater democracy and the like.

Initially, he cooperated with the new regime, but soon after had realized the defeats brought about by the Yugoslav Macedonism,[15] Brashnarov returned to the IMARO's ideas for pro-Bulgarian Independent Macedonia.[16] In 1948, being fully disappointed by the policy of the authorities, Brashnarov complained of it in letters to Joseph Stalin and to Georgi Dimitrov and asked for help, maintaining better relations with Bulgaria and the Soviet Union, and opposing the serbianization and de-Bulgarization of the Macedonian people.[6] He did so together with Pavel Shatev.[6] As a result, he was arrested in 1950 as a cominform agent under the accusation of "organizing an illegal group to support the Soviet Union in its the conflict with Yugoslavia".[17] Afterwards he was imprisoned in Goli Otok labor camp where he died the following year.[18] Initially, Brashnarov was buried in the labor camp, but two years later his remains were transferred somewhere. His grave was found in 2011 in Zagreb, where he was reburied in a mass grave of prisoners from Goli Otok.

The name of Brashnarov was taboo in the SR Macedonia during the period 1950–1990, because of the obligatory pro-Serbian and anti-Bulgarian tendency among the "socialist" Yugoslav Macedonian historians, but he was rehabilitated in North Macedonia during the 1990s, after the country gained its independence.[19] Although he was liked by the historiography in Communist Bulgaria as a left-wing pro-Bulgarian politician, after the fall of communism he has been criticized by some right-wing nationalist historians there as a late repented Macedonian Communist apostate.[20]

References

- Му ставивме споменик, не му го најдовме гробот Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- В концентрационния лагер "Голи Оток" завършва трагично своя живот изтъкнатият български патриот Панко Брашнаров от Велес. For more see: Славе Гоцев, Борби на българското население в Македония срещу чуждите аспирации и пропаганда 1878-1945, Университетско издателство "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1991, стр. 190.

- Chris Kostov, Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996; Peter Lang, 2010; ISBN 3034301960, p. 88.

- The first name of the IMARO was "Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees", which was later changed several times. Initially its membership was restricted only for Bulgarians. It was active not only in Macedonia but also in Thrace (the Vilayet of Adrianople). Since its early name emphasized the Bulgarian nature of the organization by linking the inhabitants of Thrace and Macedonia to Bulgaria, these facts are still difficult to be explained from the Macedonian historiography. They suggest that IMRO revolutionaries in the Ottoman period did not differentiate between 'Macedonians' and 'Bulgarians'. Moreover, as their own writings attest, they often saw themselves and their compatriots as 'Bulgarians' and wrote in Bulgarian standard language. For more see: Brunnbauer, Ulf (2004) Historiography, Myths and the Nation in the Republic of Macedonia. In: Brunnbauer, Ulf, (ed.) (Re)Writing History. Historiography in Southeast Europe after Socialism. Studies on South East Europe, vol. 4. LIT, Münster, pp. 165–200 ISBN 382587365X.

- Palmer, S. and R. King Yugoslav Communism and the Macedonian Question, Archon Books (June 1971), p. 137.

- "Panko Brashnarov and Pavel Shatev on the situation in Macedonia 1944-1948" - report to the All-Union Communist Party: The authors oppose Yugoslavia's policy of annexing Pirin and Aegean Macedonia. The Yugoslav Communist Party (YCP) is accused of interfering in Macedonia's domestic policy and ASNOM's activities, and of displaying extreme Serbian nationalism. They wrote that the goal pursued with the creation of the Macedonian alphabet is to Serbianize the Bulgarians in Macedonia. According to them, the Macedonian Communist Party acts entirely in the interest of the YCP and bans all Bulgarian books and newspapers, but makes an exception for Serbian ones. Bulgarian songs are also banned. The authors also wrote that the new Macedonian authorities curse everything Bulgarian, although it is a historical fact that the Ilinden insurgents were people with a Bulgarian national consciousness. The statement also reads: "The Macedonian leaders imposed by Belgrade are trying to crush everything Bulgarian without raising funds for it. Those who disagree with the YCP's policy are considered "unconscious Bulgarophiles."

- According to the Macedonian historian Academician Ivan Katardzhiev all left-wing Macedonian revolutionaries from the period until the early 1930s declared themselves as "Bulgarians" and he asserts that the political separatism of some Macedonian revolutionaties toward official Bulgarian policy was yet only political phenomenon without ethnic character. Katardzhiev claims all those veterans from IMRO (United) and Bulgarian communist party remained only at the level of political, not of national separatism. Thus, they practically continued to feel themselves as Bulgarians, i.e. they didn't developed clear national separatist position even in Communist Yugoslavia. This will bring even one of them - Dimitar Vlahov on the session of the Politburo of the Macedonian communist party in 1948, to say that in 1932 (when left wing of IMRO issued for the first time the idea of separate Macedonian nation) a mistake was made. Академик Катарџиев, Иван. Верувам во националниот имунитет на македонецот, интервју за списание "Форум", 22 jули 2000, броj 329. For more see Tchavdar Marinov, Famous Macedonia, the Land of Alexander: Macedonian Identity at the Crossroads of Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian Nationalism in Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 9789004250765, pp 273-330.

- Енциклопедичен речник за Македония и македонските работи, Цанко Серафимов, Орбел, 2004, стр. 183.

- Размисли върху революцията в Европа, Красимир Узунов, Център за изследване на демокрацията, 1992, София, стр. 74.

- Newspaper Makedonsko Delo, Vienna, No. 93-94, July 25, 1929; the original is in Bulgarian.

- Minchev, Dimitre. Bulgarian Campaign Committees in Macedonia - 1941 (Минчев, Димитър. Българските акционни комитети в Македония - 1941, София 1995, с. 28, 96-97)

- Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia: A History of Its Demise, Routledge, 2005, ISBN 1134665113, p. 181.

- Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies, Roumen Dontchev Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, BRILL, 2013, p. 328., ISBN 900425076X

- Because the Communists as well as the whole left wing of the Macedonian national-revolutionary movement treated the Macedonian Slavs as a regional section of the Bulgarian nation up to the middle of the 1930s, the main reason for Cominformism in Macedonia was opposition to the new national policy in Yugoslav Macedonia and support for the old pro-Bulgarian option. For more see: Ivo Banac: With Stalin Against Tito. Cominformist Splits in Yugoslav Communism, Ithaca/London, 1988, p. 192.

- Църнушанов, Коста. Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него, Университетско издателство "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1992, стр. 275-282, 390-393.

- Heinz Willemsen, The Labour Movement and the National Question: The Communist Party of Yugoslavia in Macedonia in the Inter-War Period, Vol. 33 (2005): Social Movements in Southeast Europe, p. 102.

- Goli Otok: The Island of Death: a Diary in Letters, Venko Markovski, Social Science Monographs, Boulder, 1984, ISBN 0880330554, р. 42.

- Stefan Troebst, Historical Politics and Historical 'Masterpieces' in Macedonia before and after 1991, New Balkan Politics, issue 6, 2003.

- Цочо В. Билярски, Закъснялото осъзнаване на разкаялите се родоотстъпници Павел Шатев и Панко Брашнаров, 24.04.2010, Сите българи заедно.

Sources

- Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev Scarecrow Press, 2009, Panko Brashnarov, p. 30., ISBN 0810862956

- Веселин Ангелов,"Македонският въпрос в българо-югославските отношения (1944–1952)", УИ "Св. Климент Охридски", София 2005, стр. 437-444 (in Bulgarian)

- Speech on United Macedonia and the army of the Macedonians "the struggle of the Ilinden combatants with that one of the young Macedonian Army... for an ideal achievement - liberated and united Macedonia"