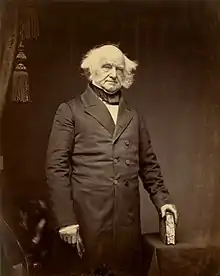

Papers of Martin Van Buren

The Papers of Martin Van Buren is an ongoing project that aims to make available to the public all the surviving letters, papers, and other documents from eighth President Martin Van Buren’s lifetime.[1] The project was originally founded in 1969 at Pennsylvania State University, where a microfilm edition of over 13,000 documents was published in 1987. In 2014, Cumberland University relaunched the Papers of Martin Van Buren project with the goal of digitizing the documents and releasing them online for free access.[2]

Description of Van Buren Papers

Like many of his contemporaries, Martin Van Buren understood the importance of his papers and viewed them as historical records. He took care to preserve a large amount of his own correspondence as well as other documents he believed would document his career. He was especially careful to preserve the letters between himself and Andrew Jackson, and during his lifetime, he recovered as much of their correspondence as he could with the aim of publication. These letters then passed to his sons, who preserved the collection intact.[3][4]

Van Buren did not view his mundane or social letters with equal importance and as such, he destroyed many of these letters. His surviving letters show that Van Buren kept up a steady correspondence with several women; however, hardly any of their responses still exist. Van Buren was also careful to destroy confidential letters at the request of their authors. Because of this, the majority of the collection is limited to his political career.[3][4]

History of the project

The Papers of Martin Van Buren project was officially launched at Pennsylvania State University (PSU) in 1969, headed by Dr. Walter L. Ferree. Previously, Van Buren’s papers were scattered among several different depositories, including the Library of Congress, and many were held in private hands. Dr. Ferree’s team worked to gather these documents into a single, comprehensive collection. A total of 260 repositories eventually contributed to the 13,000 documents published in the microfilm edition.[5]

The original goal of the project was to release a letterpress edition, which would be published in two series, totaling fifteen to twenty volumes. The team worked for three years, transcribing handwritten documents and beginning the editing process, before deciding in 1972 to shelve the publication and instead focus on producing a microfilm edition. At the time, the benefits of a microfilm edition made it appear as the only viable route: the publication cost would be far lower; the collection would be available in a period of four or five years rather than the twenty it would take to release a letterpress edition; and the technology of the time was headed in a direction that anticipated microfilm as the best way to access resource material.[5]

In 1976, Ferree retired, and Dr. George Franz of PSU took over leadership.[6][7] He worked on the project part time until a full-time editor was finally appointed to the project. Lucy Fisher West of Bryn Mawr College took this full-time position in 1986, and the project was completed in 1987. The microfilm edition was published by Chadwyck-Healey, Inc., and it included a comprehensive index compiled by West.[8][9][10]

The Papers of Martin Van Buren project was revived in 2014 when Mark Cheathem and James Bradley embarked on a mission to digitize the Papers of Martin Van Buren at Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee.[11] The project was officially launched in February 2016 and has partnered with the University of Virginia's Center for Digital Editing.[12][13]

Editors/project directors[4][8]

- Walter L. Ferree, founding editor and director (1969–1976)

- George Franz, project director and editor (1976–1988)[7]

- Lucy Fisher West, project director and editor (1986–1987)

- Mark Cheathem, project director and co-editor (2014–present)

- James Bradley, co-editor (2014–present)

Microfilm edition staff[4]

- Phillip E. Stebbins, associate editor, legal papers

- Rachel M. Dach, assistant editor

- Joan D. Berger, editorial assistant

- S. Emma McCoach, assistant to the editor

- Joan E. Locke, secretary

- Elizabeth Gentile, editorial aide

- Lorranie M. Poll, editorial aide

- Louise Bearwood, reference librarian

- Ann B. Newberry, secretary

- Beth Jones, typist

- Fay Shoyer, typist

- Margaret Kirkman, typist

- Jane Kim, typist

- Grace Boileau, typist

- Lorraine E. Manners, typist

- Miss Konuch, typist

- Marc Gallicchio, graduate student assistant

- Kathryn Langan, student assistant

- Elma Key Sabo, student assistant

- Leslie Lock, student assistant

- Christopher J. Benedict, graduate student assistant

- Lynore Elansky, student assistant

- Ann Oscilowski Taylor, student assistant

- Warren Faust, Graduate student assistant

Microfilm edition advisory board[4]

- Glyndon G. Van Deusen

- Roy Franklin Nichols

- Donald B. Cole

- Philip S. Klein

- Charles M. Wiltse

- David Herbert Donald

- Frank O. Gatell

- Holman Hamilton

- Leo Hershkowitz

- Chris W. Kentera

- Edward Pessen

- Robert V. Remini

- Donald M. Roper

- Sam B. Smith

- T. Rowland Slingluff, Jr.

- Charles Grier Sellers

Digital edition staff (Cumberland University)[14]

- Andrew Wiley, associate editor (2018–present)

- Katie Hatton, associate editor (2019–present)

- David Gregory, associate editor (2018)

- Josh Williams, graduate assistant (2016–17)

- David Gregory, graduate assistant (2017–18)

- Daniel Barr, graduate assistant (2018)

- Ally Johnson, graduate assistant (2018–20)

Digital edition staff (Center for Digital Editing)[14][15]

- Jennifer Stertzer, Center for Digital Editing director (2016–present)

- Erica Cavanaugh, Center for Digital Editing project developer (2016–present)

- Katie Blizzard, Center for Digital Editing research editor and communications specialist (2017–present)

Digital edition advisory board[8]

- Dr. John L. Brooke, Humanities Distinguished Professor of History, The Ohio State University

- Dr. Eric Cummings, Dean, School of Humanities, Education, and the Arts, Cumberland University

- Dr. George Franz, Pennsylvania State University Brandywine (emeritus), former project director and editor, The Papers of Martin Van Buren microfilm edition

- Dr. Reeve Huston, Associate Professor of History, Duke University

- Prof. Jennifer Stertzer, Senior Editor, The Papers of George Washington and the Center for Digital Editing, University of Virginia

- Dr. John F. Marszalek, Chief Editor, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Mississippi State University

- Dr. C. William McKee, Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs, Cumberland University

- Ms. Ruth Piwonka, Historian, Columbia County, New York

- Dr. Harry L. Watson, Atlanta Alumni Distinguished Professor of Southern Culture, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Editing process

A Martin Van Buren document is defined as “one written in his hand, at his instruction, and/or with his signature; a printed speech or public remarks verifiable as his own; and correspondence addressed directly to him.”[8] Once a document is identified as an MVB document, the editors and project staff workers begin the transcription and editing process.

In transcription, the microfilm document is consulted, and a typed version is produced. The resultant transcribed document matches the original as close as possible, retaining errors such as misspelled words and unconventional capitalization. Very few minor editorial changes are made to make the documents more readable, such as deleting repeated words and changing end dashes to conventional punctuation. An exhaustive list of these changes is available on the project website.[16]

In many cases, Martin Van Buren’s and his contemporaries’ handwriting is difficult to read. The Papers of Martin Van Buren project aims to release completed transcriptions, but the editorial staff share the opinion of the editors at the Jane Addams Papers, who believe it is better to publish 99% of a document instead of waiting to get that last 1%.[17] Documents published on the Van Buren Papers website are all verified first-pass transcriptions: they have been reviewed by an editor once but may still have errors and missing words. Utilizing this approach allows the editors to make documents accessible quickly, and the digital format allows for later revision.

Series

The digital edition is organized into fourteen series.

- Kinderhook Years (Dec. 1782 – Dec. 1811): Childhood and time as lawyer and local politician.

- Albany Years (Jan. 1812 – 16 Feb. 1815): State senator and War of 1812 prosecutor.

- Attorney General and Party Leader (17 Feb. 1815 – Dec. 1820): Attorney general, state senator, founder of Albany Regency, member of state constitutional convention.

- U.S. Senator (Jan. 1821 – Dec. 1824): U.S. Senator, supporter of William Crawford for president in 1824 election.

- U.S. Senator (Jan. 1825 – 3 March 1829): Reconciliation with DeWitt Clinton, support for Andrew Jackson, formation of Jacksonian Democratic coalition, election of 1828, gubernatorial tenure.

- U.S. Secretary of State and U.S. Minister to England (4 March 1829 – 3 March 1833): Jackson’s secretary of state, Eaton affair, minister to England, vice-presidential candidate in 1832 election.

- Vice President (4 March 1833 – 3 March 1837): Vice-presidential duties, Bank War, 1836 election.

- President, pt. 1 (4 March 1837 – Dec. 1837): Panic of 1837, independent treasury, Indian Removal, etc.

- President, pt. 2 (Jan.–Dec. 1838): Economic issues, independent treasury, Indian removal, etc.

- President, pt. 3 (Jan.–Dec. 1839): Panic of 1839, independent treasury, border conflicts, campaign tour through mid-Atlantic states, etc.

- President, pt. 4 (Jan. 1840 – 4 March 1841): Independent treasury, border conflicts, Amistad case, 1840 election, etc.

- Defeat and 1844 Campaign (5 March 1841 – Dec. 1844): Return to Kinderhook, 1842 national tour, Texas annexation, 1844 Democratic convention, 1844 election.

- Move to Free Soil Party (Jan. 1845 – Dec. 1848): Break from James K. Polk and Democratic Party, Free Soil Party nomination, 1848 election.

- Retirement (Jan. 1849 – 24 July 1862): Farming, family life, political correspondence, support for Abraham Lincoln in Civil War, death.[16]

Funding

The Papers of Martin Van Buren first received endorsement from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC)—then the National Historical Publications Commission (NHPC)—in 1969, and it began receiving NHPC funding in 1971.[4]

After the project’s relaunch, the NHPRC again provided funding by awarding the papers project an initial grant in 2017.[18] The project also received grants in 2018 and 2019.[19][20]

In 2018, the project received another grant from the Watson-Brown Foundation that provided funding to hire an assistant editor and associate editor. It also allowed Cumberland University to provide scholarships for students interested in working on the project.[21]

The future of the project

The Papers of Martin Van Buren website is updated regularly as documents are completed. All of these documents are free to access. Once the project is completed, annotated versions of the papers will be available through a subscription with the University of Virginia’s Rotunda platform. The project is also publishing an annotated four-volume print edition of Van Buren’s most important letters and speeches.[22]

See also

References

- "The Strange Case of the Papers of Martin Van Buren". Nashville Scene. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- "Cumberland to help digitize presidential papers". The Tennessean. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- Schouler, James (April 1903). "Calhoun, Jackson, and Van Buren Papers". Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Second Series, Vol. 18: 459–65.

- West, Lucy Fisher (1989). The Papers of Martin Van Buren: Guide and Index to General Correspondence and Miscellaneous Documents. Alexandria, VA: Chadwyck-Healey. pp. 5–17. ISBN 978-0898870541.

- "Cameo Description of the Van Buren Papers." Papers of Martin Van Buren Project Archives, Cornell University, 1974.

- "Papers of Martin Van Buren Project Records, 1737-1987". Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- "Franz Webpage--PSU Brandywine".

- "Project History". Van Buren Papers. 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Cole, Donald B. (1993). "The Papers of Martin Van Buren". The Journal of American History. 79 (4): 1702. doi:10.2307/2080370. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 2080370.

- TRIPP, WENDELL (1992). "The Papers of Martin Van Buren: Guide and Index to General Correspondence and Miscellaneous Documents (review)". New York History. 73 (1): 121. JSTOR 23182098.

- Sisk, Chas. "A Middle Tennessee University Works To Elevate A Forgotten President — One Page At A Time". Nashville Public Radio. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- "Papers of Martin Van Buren press conference". Lebanon Democrat. February 15, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- "Projects | Center for Digital Editing". Center for Digital Editing.

- "Editorial Staff". Van Buren Papers. 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "About Us | Center for Digital Editing". Center for Digital Editing.

- "Editorial Process". Van Buren Papers. 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Hajo, Cathy Moran (May 11, 2016). "What Did Jane Write? Publishing Transcribed Documents in a Digital Edition". The Jane Addams Papers Project. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "NHPRC Grants - May 2017". National Historical Publications & Records Commission. April 4, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "NHPRC Grants, 2018-19".

- "Cumberland University Papers of Martin Van Buren Project Receives $143,888 Grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission". Cumberland University. 2019-05-22. Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- "Van Buren Papers Receives Major Grant". Van Buren Papers. 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "CU launches project on papers of Martin Van Buren". Cumberland University. February 11, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2018.