Indian removal

Indian removal was a forced migration in the 19th century whereby Native Americans were forced by the United States government to leave their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River, specifically to a designated Indian Territory (roughly, modern Oklahoma).[1][2][3] The Indian Removal Act, the key law that forced the removal of the Indians, was signed by Andrew Jackson in 1830. Jackson took a hard line on Indian removal, but the law was put into effect primarily under the Martin van Buren administration.[4][5]

| Indian removal | |

|---|---|

Routes of southern removals | |

| Location | United States |

| Date | 1830–1847 |

| Target | Native Americans in the eastern United States |

Attack type | Population transfer, ethnic cleansing |

| Deaths | 8,000+ (lowest estimate) |

| Perpetrators | United States |

| Motive | Expansionism |

Indian removal, a popular policy among white settlers, was a consequence of actions first by European settlers to North America in the colonial period, then by the United States government and its citizens until the mid-20th century.[6][7] The policy traced its direct origins to the administration of James Monroe, though it addressed conflicts between European Americans and Native Americans that had been occurring since the 17th century, and were escalating into the early 19th century as white settlers were continually pushing westward.

The Revolutionary background

American leaders in the Revolutionary and Early National era debated whether the American Indians should be treated officially as individuals or as nations in their own right.[8] Some of these views are summarized below.

Benjamin Franklin

In a draft, "Proposed Articles of Confederation", presented to the Continental Congress on May 10, 1775, Benjamin Franklin called for a "perpetual Alliance" with the Indians for the nation about to take birth, especially with the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy:[9][10]

Article XI. A perpetual Alliance offensive and defensive, is to be entered into as soon as may be with the Six Nations; their Limits to be ascertained and secured to them; their Land not to be encroached on, nor any private or Colony Purchases made of them hereafter to be held good; nor any Contract for Lands to be made but between the Great Council of the Indians at Onondaga and the General Congress. The Boundaries and Lands of all the other Indians shall also be ascertained and secured to them in the same manner; and Persons appointed to reside among them in proper Districts, who shall take care to prevent Injustice in the Trade with them, and be enabled at our general Expense by occasional small Supplies, to relieve their personal Wants and Distresses. And all Purchases from them shall be by the Congress for the General Advantage and Benefit of the United Colonies.

Thomas Jefferson

In his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), Thomas Jefferson defended American Indian culture and marveled at how the tribes of Virginia "never submitted themselves to any laws, any coercive power, any shadow of government" due to their "moral sense of right and wrong".[11][12] He would later write to the Marquis de Chastellux in 1785, "I believe the Indian then to be in body and mind equal to the whiteman".[13] His desire, as interpreted by Francis Paul Prucha, was for the Native Americans to intermix with European Americans and to become one people.[14][15] To achieve that end, Jefferson would, as president, offer U.S. citizenship to some Indian nations, and propose offering credit to them to facilitate their trade.[16][17]

George Washington

President George Washington, in his address to the Seneca nation in 1790, describing the pre-Constitutional Indian land sale difficulties as "evils", asserted that the case was now entirely altered, and publicly pledged to uphold their "just rights".[18][19] In March and April 1792, Washington met with 50 tribal chiefs in Philadelphia—including the Iroquois—to discuss closer friendship between them and the United States.[20] Later that same year, in his Fourth Annual Message to Congress, Washington stressed the need for building peace, trust, and commerce with America's Indian neighbors:[21]

I cannot dismiss the subject of Indian affairs without again recommending to your consideration the expediency of more adequate provision for giving energy to the laws throughout our interior frontier, and for restraining the commission of outrages upon the Indians; without which all pacific plans must prove nugatory. To enable, by competent rewards, the employment of qualified and trusty persons to reside among them, as agents, would also contribute to the preservation of peace and good neighbourhood. If, in addition to these expedients, an eligible plan could be devised for promoting civilization among the friendly tribes, and for carrying on trade with them, upon a scale equal to their wants, and under regulations calculated to protect them from imposition and extortion, its influence in cementing their interests with our's [sic] could not but be considerable.[22]

In 1795, in his Seventh Annual Message to Congress, Washington intimated that if the U.S. government wanted peace with the Indians, then it must give peace to them, and that if the U.S. wanted raids by Indians to stop, then raids by American "frontier inhabitants" must also stop.[23][24]

Early Congressional acts

The Confederation Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which would serve broadly as a precedent for the manner in which the United States' territorial expansion would occur for years to come, calling for the protection of Indians' "property, rights, and liberty":[25] The U.S. Constitution of 1787 (Article I, Section 8) makes Congress responsible for regulating commerce with the Indian tribes. In 1790, the new U.S. Congress passed the Indian Nonintercourse Act (renewed and amended in 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834) to protect and codify the land rights of recognized tribes.[26]

Jeffersonian policy

As president, Thomas Jefferson developed a far-reaching Indian policy that had two primary goals. First, the security of the new United States was paramount, so Jefferson wanted to assure that the Native nations were tightly bound to the United States, and not other foreign nations.[27] Second, he wanted "to civilize" them into adopting an agricultural, rather than a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.[14] These goals would be achieved through the development of trade and the signing of treaties.[28]

Jefferson initially promoted an American policy that encouraged Native Americans to become assimilated, or "civilized".[29] As president, Jefferson made sustained efforts to win the friendship and cooperation of many Native American tribes, repeatedly articulating his desire for a united nation of both whites and Indians,[30] as in a letter to the Seneca spiritual leader, Handsome Lake, dated November 3, 1802:

Go on then, brother, in the great reformation you have undertaken.... In all your enterprises for the good of your people, you may count with confidence on the aid and protection of the United States, and on the sincerity and zeal with which I am myself animated in the furthering of this humane work. You are our brethren of the same land; we wish your prosperity as brethren should do. Farewell.[31]

When a delegation from the Upper Towns of the Cherokee Nation lobbied Jefferson for the full and equal citizenship George Washington had promised to Indians living in American territory, his response indicated that he was willing to accommodate citizenship for those Indian nations that sought it.[32] In his Eighth Annual Message to Congress on November 8, 1808, he presented to the nation a vision of white and Indian unity:

With our Indian neighbors the public peace has been steadily maintained.... And, generally, from a conviction that we consider them as part of ourselves, and cherish with sincerity their rights and interests, the attachment of the Indian tribes is gaining strength daily... and will amply requite us for the justice and friendship practiced towards them.... [O]ne of the two great divisions of the Cherokee nation have now under consideration to solicit the citizenship of the United States, and to be identified with us in laws and government, in such progressive manner as we shall think best.[33]

As some of Jefferson's other writings illustrate, however, he was ambivalent about Indian assimilation, even going so far as to use the words "exterminate" and "extirpate" regarding tribes that resisted American expansion and were willing to fight to defend their lands.[34] Jefferson's intention was to change Indian lifestyles from hunting and gathering to farming, largely through "the decrease of game rendering their subsistence by hunting insufficient".[35] He expected that the switch to agriculture would make them dependent on white Americans for trade goods and therefore more likely to give up their land in exchange, or else be removed to lands west of the Mississippi.[36][37] In a private 1803 letter to William Henry Harrison, Jefferson wrote:[38]

Should any tribe be foolhardy enough to take up the hatchet at any time, the seizing the whole country of that tribe, and driving them across the Mississippi, as the only condition of peace, would be an example to others, and a furtherance of our final consolidation.[39]

Elsewhere in the same letter, Jefferson spoke of protecting the Indians from injustices perpetrated by whites:

Our system is to live in perpetual peace with the Indians, to cultivate an affectionate attachment from them, by everything just and liberal which we can do for them within... reason, and by giving them effectual protection against wrongs from our own people.[40]

By the terms of the treaty of February 27, 1819, the U.S. government would again offer citizenship to the Cherokees who lived east of the Mississippi River, along with 640 acres of land per family.[41][42][43] Native American land was sometimes purchased, either via a treaty or under duress. The idea of land exchange, that is, that Native Americans would give up their land east of the Mississippi in exchange for a similar amount of territory west of the river, was first proposed by Jefferson in 1803 and had first been incorporated in treaties in 1817, years after the Jefferson presidency. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 incorporated this concept.[37]

Calhoun's plan

Under President James Monroe, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun devised the first plans for Indian removal. By late 1824, Monroe approved Calhoun's plans and in a special message to the Senate on January 27, 1825, requested the creation of the Arkansaw Territory and Indian Territory. The Indians east of the Mississippi were to voluntarily exchange their lands for lands west of the river. The Senate accepted Monroe's request and asked Calhoun to draft a bill, which was killed in the House of Representatives by the Georgia delegation. President John Quincy Adams assumed the Calhoun–Monroe policy and was determined to remove the Indians by non-forceful means,[44][45] but Georgia refused to submit to Adams' request, forcing Adams to make a treaty with the Cherokees granting Georgia the Cherokee lands.[46] On July 26, 1827, the Cherokee Nation adopted a written constitution modeled after that of the United States which declared they were an independent nation with jurisdiction over their own lands. Georgia contended that it would not countenance a sovereign state within its own territory, and proceeded to assert its authority over Cherokee territory.[47] When Andrew Jackson became president as the candidate of the newly organized Democratic Party, he agreed that the Indians should be forced to exchange their eastern lands for western lands and relocate to them, and enforced Indian removal policy vigorously.[48][46]

Opposition to removal from US citizens

While Indian removal was a popular policy, there was also opposition. This opposition stemmed from the fact that this was not legal or moral. It was also against the formal diplomatic way of interaction between the US federal government and the different Native nations. For example, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote a widely published letter, “A Protest Against the Removal of the Cherokee Indians from the State of Georgia”, in 1838, shortly before the Cherokee removal occurred. He criticizes the government and the removal policy, declaring that the removal treaty made was not legitimate, that it was a “sham treaty” that the US government should not uphold.[49] He describes removal as “such a dereliction of all faith and virtues, such a denial of justice…in the dealing of a nation with its own allies and wards since the earth was made…a general expression of despondency, of disbelief, that any goodwill accrues from a remonstrance on an act of fraud ad robbery, appeared in those men to whom we naturally turn for aid and counsel”.[50] He concludes the letter by stating that this should not be a political issue and urging President Martin van Buren should stop the Cherokees’ removal from being enforced.

Other people throughout the country, as well as social organizations, advocated against removal.[51]

Native Americans' response to removal

Native groups reshaped their governments, made constitutions and legal codes, and sent delegates to Washington to negotiate various policies and treaties to uphold their autonomy and ensure protection from white states, that the federal government promised them.[52] They thought that doing all this, and acculturating as the US wanted them to, would stem removal policy and create a better relationship with the US government and surrounding states. The Native American nations had different views about Removal. Whereas most wanted to remain in their native lands and do whatever possible to make this a reality, others believed to maintain their autonomy, and their cultural Removal to an area not surrounded by white united states citizens was the only option.[53] The US utilized this division to write removal treaties with the, often, minority groups who became convinced that Removal was the best option for their people.[54] These treaties were often not acknowledged by most of the people in the Native nation. Once Congress ratified the Removal treaty, the US government could use force through soldiers to remove the Native nations if they have left or started moving by the time meant in the Removal treaty.

Indian Removal Act

| Part of a series on |

| Native Americans |

|---|

When Andrew Jackson assumed office as president of the United States in 1829, his government took a hard line on Indian Removal policy.[55] Jackson abandoned the policy of his predecessors of treating different Indian groups as separate nations. Instead, he aggressively pursued plans against all Indian tribes which claimed constitutional sovereignty and independence from state laws, and which were based east of the Mississippi River. They were to be removed to reservations in Indian Territory west of the Mississippi (now Oklahoma), where their laws could be sovereign without any state interference. At Jackson's request, the United States Congress opened a debate on an Indian Removal Bill. After fierce disagreements, the Senate passed the measure 28–19, the House 102–97. Jackson signed the legislation into law May 30, 1830.[56]

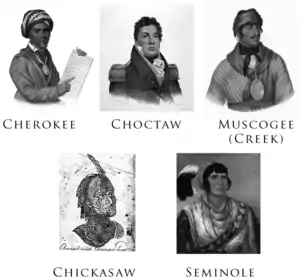

In 1830, the majority of the "Five Civilized Tribes"—the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee—were living east of the Mississippi. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 implemented the federal government's policy towards the Indian populations, which called for moving Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river. While it did not authorize the forced removal of the indigenous tribes, it authorized the president to negotiate land exchange treaties with tribes located in lands of the United States.[57]

Choctaw

On September 27, 1830, the Choctaw signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek and by concession, became the first Native American tribe to be removed. The agreement represented one of the largest transfers of land that was signed between the U.S. Government and Native Americans without being instigated by warfare. By the treaty, the Choctaw signed away their remaining traditional homelands, opening them up for European-American settlement in Mississippi Territory. When the Choctaw reached Little Rock, a Choctaw chief referred to the trek as a "trail of tears and death".[58]

In 1831, Alexis de Tocqueville, the French historian and political thinker, witnessed an exhausted group of Choctaw men, women and children emerging from the forest during an exceptionally cold winter near Memphis, Tennessee,[59] on their way to the Mississippi to be loaded onto a steamboat, and wrote:

In the whole scene there was an air of ruin and destruction, something which betrayed a final and irrevocable adieu; one couldn't watch without feeling one's heart wrung. The Indians were tranquil, but sombre and taciturn. There was one who could speak English and of whom I asked why the Chactas were leaving their country. "To be free," he answered, could never get any other reason out of him. We ... watch the expulsion ... of one of the most celebrated and ancient American peoples.[60]

Cherokee

While the Indian Removal Act made the move of the tribes voluntary, it was often abused by government officials. The best-known example is the Treaty of New Echota, which was negotiated and signed by a small faction of only twenty Cherokee tribal members, not the tribal leadership, on December 29, 1835.[61] Most of the Cherokees later blamed them and the treaty for the forced relocation of the tribe in 1838.[62] An estimated 4,000 Cherokees died in the march, now known as the Trail of Tears.[63] Missionary organizer Jeremiah Evarts urged the Cherokee Nation to take their case to the U.S. Supreme Court.[64]

The Marshall court heard the case in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), but declined to rule on its merits, instead declaring that the Native American tribes were not sovereign nations, and had no status to "maintain an action" in the courts of the United States.[65][66] In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the court held, in an opinion written by Chief Justice Marshall, that individual states had no authority in American Indian affairs.[67][68]

Yet the state of Georgia defied the Supreme Court ruling,[67] and the desire of white settlers and land speculators for Indian lands continued unabated.[69] Some whites claimed that the Indian presence was a threat to peace and security; the Georgia legislature passed a law that after March 31, 1831, forbade whites from living on Indian territory without a license from the state, in order to exclude white missionaries who opposed Indian removal.[70][71]

Seminole

In 1835, the Seminole people refused to leave their lands in Florida, leading to the Second Seminole War. Osceola was a war leader of the Seminole in their fight against removal. Based in the Everglades of Florida, Osceola and his band used surprise attacks to defeat the U.S. Army in many battles. In 1837, Osceola was seized by deceit upon the orders of U.S. General Thomas Jesup when Osceola came under a flag of truce to negotiate a peace near Fort Peyton.[72] Osceola died in prison of illness. The war would result in over 1,500 U.S. deaths and cost the government $20 million.[73] Some Seminole traveled deeper into the Everglades, while others moved west. Removal continued out west and numerous wars ensued over land.

Muskogee (Creek)

In the aftermath of the Treaty of Fort Jackson and the Treaty of Washington, the Muscogee were confined to a small strip of land in present-day east central Alabama. Following the Indian Removal Act, in 1832 the Creek National Council signed the Treaty of Cusseta, ceding their remaining lands east of the Mississippi to the U.S., and accepting relocation to the Indian Territory. Most Muscogee were removed to Indian Territory during the Trail of Tears in 1834, although some remained behind. In 1836, the second Creek war resulted in the end of Government attempts to convince the creek population to leave voluntarily. However, Creeks who had not participated in the war were not forced west at the end of a gun as with many others. The Creek population was placed into camps and told they were to be relocated soon. Many of the Creek leaders were surprised by the quick departure but could do little to challenge it. The 16000 Creeks were organized into 5 detachments that were to be sent west to Fort Gibson. The Creek leaders did their best to negotiate better conditions and succeeded in obtaining important items such as wagons and medicine. In preparation for the relocation, Creeks began to deconstruct their spiritual lives. They burned piles of lightwood over ancestors' graves to honor their memories. They also prepared and polished the sacred plates that would travel at the front of each group. They also prepared financially by selling what they could not take. Many were taken advantage of by local merchants and swindled out of their valuable possessions such as land, and the military had to intervene. The detachments began moving west in September 1836. As they moved west they faced harsh conditions. Despite the preparations made, the detachments found themselves facing bad roads, horrible weather, and a lack of drinkable water. When all five detachments reached their destination they recorded the death toll. Detachment one had 2,318 Creeks with 78 deaths. Detachment two had 3,095 Creeks with 37 deaths. Detachment three had 2,818 Creeks with 12 deaths. Detachment four had 2,330 Creeks with 36 deaths. Detachment five had 2,087 Creeks with 25 deaths.[74]

Friends and Brothers – By permission of the Great Spirit above, and the voice of the people, I have been made President of the United States, and now speak to you as your Father and friend, and request you to listen. Your warriors have known me long. You know I love my white and red children, and always speak with a straight, and not with a forked tongue; that I have always told you the truth ... Where you now are, you and my white children are too near to each other to live in harmony and peace. Your game is destroyed, and many of your people will not work and till the earth. Beyond the great River Mississippi, where a part of your nation has gone, your Father has provided a country large enough for all of you, and he advises you to remove to it. There your white brothers will not trouble you; they will have no claim to the land, and you can live upon it you and all your children, as long as the grass grows or the water runs, in peace and plenty. It will be yours forever. For the improvements in the country where you now live, and for all the stock which you cannot take with you, your Father will pay you a fair price ...

— President Andrew Jackson addressing the Creek, 1829.[56]

Chickasaw

Unlike other tribes who exchanged land grants, the Chickasaw were to receive mostly financial compensation of $3 million from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River.[75][76] In 1836, the Chickasaw reached an agreement that purchased land from the previously removed Choctaw after a bitter five-year debate, paying them $530,000 for the westernmost part of Choctaw land.[77][78] Most of the Chickasaw moved in 1837–1838.[79] The $3,000,000 that the U.S. owed the Chickasaw went unpaid for nearly 30 years.[80]

Aftermath

As a result, the Five Civilized Tribes were resettled in the new Indian Territory in modern-day Oklahoma.[81] The Cherokee occupied the northeast corner of the Territory, as well as a strip of land seventy miles wide in Kansas on the border between the two.[82] Some indigenous nations resisted forced migration more strongly.[83][84] Those few that stayed behind eventually formed tribal groups,[85] including the Eastern Band of Cherokee based in North Carolina,[86][87][88] the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians,[89][90] the Seminole Tribe of Florida,[91][92][93] and the Creeks in Alabama,[94] including the Poarch Band.[95][96][97]

Details on removals

The North

Tribes in the Old Northwest were far smaller and more fragmented than the Five Civilized Tribes, so the treaty and emigration process was more piecemeal.[98] Bands of Shawnee,[99] Ottawa, Potawatomi,[100] Sauk, and Meskwaki (Fox) signed treaties and relocated to the Indian Territory.[101] In 1832, a Sauk leader named Black Hawk led a band of Sauk and Fox back to their lands in Illinois; in the ensuing Black Hawk War, the U.S. Army and Illinois militia defeated Black Hawk and his warriors, resulting in the Sauk and Fox being relocated into what would become present day Iowa.[102]

Tribes further to the east, such as the already displaced Lenape (or Delaware tribe), as well as the Kickapoo and Shawnee, were removed from Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio in the 1820s.[103] The Potawatomi were forced out in late 1838 and resettled in Kansas Territory. Many Miami were resettled to Indian Territory in the 1840s.[104] Communities in present-day Ohio were forced to move to Louisiana, which was then controlled by Spain.[105]

By the terms of the Second Treaty of Buffalo Creek (1838), the Senecas transferred all their land in New York, excepting one small reservation, in exchange for 200,000 acres of land in Indian Territory. The U.S. federal government would be responsible for the removal of those Senecas who opted to go west, while the Ogden Land company would acquire their lands in New York. The lands were sold by government officials, however, and the money deposited in the U.S. Treasury. The Senecas asserted that they had been defrauded, and sued for redress in the U.S. Court of Claims. The case was not resolved until 1898, when the United States awarded $1,998,714.46 in compensation to "the New York Indians".[106] In 1842 and 1857, the U.S. signed treaties with the Senecas and the Tonawanda Senecas, respectively. Under the treaty of 1857, the Tonawandas renounced all claim to lands west of the Mississippi in exchange for the right to buy back the lands of the Tonawanda reservation from the Ogden Land Company.[107] Over a century later, the Senecas purchased a nine-acre plot (part of their original reservation) in downtown Buffalo to build the "Seneca Buffalo Creek Casino".[108]

The South

The following is a compilation of the statistics, many containing rounded figures, regarding the Southern removals.

| Nation | Population east of the Mississippi before removal treaty | Removal treaty & year signed |

Years of major emigration | Total number emigrated or forcibly removed | Number stayed in Southeast | Deaths during removal | Deaths from warfare |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choctaw | 19,554[109] + white citizens of the Choctaw Nation + 500 black slaves | Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830) | 1831–1836 | 12,500 | 7,000[110] | 2,000–4,000+ (Cholera) | none |

| Creek | 22,700 + 900 black slaves[111] | Cusseta (1832) | 1834–1837 | 19,600[112] | 100s | 3,500 (disease after removal)[113] | ? (Second Creek War) |

| Chickasaw | 4,914 + 1,156 black slaves | Pontotoc Creek (1832) | 1837–1847 | over 4,000 | 100s | 500–800 | none |

| Cherokee | 21,500 + 2,000 black slaves |

New Echota (1835) | 1836–1838 | 20,000 + 2,000 slaves | 1,000 | 2,000–8,000 | none |

| Seminole | 5,000 + fugitive slaves | Payne's Landing (1832) | 1832–1842 | 2,833[114] | 250[114] 500[115] |

700 (Second Seminole War) |

Changing perspective on the policy

Historical views regarding the Indian Removal have been re-evaluated since that time. Widespread acceptance at the time of the policy, due in part to an embracing of the concept of Manifest destiny by the general populace, have since given way to somewhat harsher views. Descriptions such as "paternalism",[116][117] ethnic cleansing,[118] and even genocide[4] have been ascribed by historians past and present to the motivation behind the Removals.

Jackson's reputation

Andrew Jackson's reputation took a blow for his treatment of the Indians. Historians who admire Jackson's strong presidential leadership, such as Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., would skip over the Indian question with a footnote. Writing in 1969, Francis Paul Prucha argued that Jackson's removal of the Five Civilized Tribes from the very hostile white environment in the Old South to Oklahoma probably saved their very existence.[119] In the 1970s, however, Jackson came under sharp attack from writers such as Michael Paul Rogin and Howard Zinn, chiefly on this issue. Zinn called him "exterminator of Indians";[120][121] Paul R. Bartrop and Steven Leonard Jacobs argue that Jackson's policies did not meet the criterion for genocide or cultural genocide.[117]

See also

Citations and notes

- It has been called ethnic cleansing. The National Museum of the American Indian refers to the policy as genocide.

- Gary Clayton Anderson (2014). Ethnic Cleansing and the Indian: The Crime That Should Haunt America. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8061-4508-2.

Even though the term "ethnic cleansing" has been applied mainly to the history of nations other than the United States, no term better fits the policy of United States "Indian Removal".

- The "Indian Problem" (Video). 10:51–11:17: National Museum of the American Indian. March 3, 2015. Event occurs at 12:21. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

When you move a people from one place to another, when you displace people, when you wrench people from their homelands... wasn't that genocide? We don't make the case that there was genocide. We know there was. Yet here we are.

CS1 maint: location (link) - Lewey, Guenter (September 1, 2004). "Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide?". Commentary. Retrieved March 8, 2017. Also available in reprint from the History News Network.

- John Docker (2008). "Are Settler-Colonies Inherently Genocidal? Re-reading Lemkin". In A. Dirk Moses (ed.). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Berghahn Books. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-78238-214-0.

- Rajiv Molhotra (2009). "The Challenge of Eurocentrism". In Rajani Kannepalli Kanth (ed.). The Challenge of Eurocentrism: Global Perspectives, Policy, and Prospects. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 180, 184, 189, 199. ISBN 978-0-230-61227-3.

- Paul Finkelman; William W. Freehling; Tim Alan Garrison (2008). Paul Finkelman; Donald R. Kennon (eds.). Congress and the Emergence of Sectionalism: From the Missouri Compromise to the Age of Jackson. Ohio University Press. pp. 15, 141, 254. ISBN 978-0-8214-1783-6.

- Sharon O'Brien, "Tribes and Indians: With whom does the United States maintain a relationship." Notre Dame L. Rev. 66 (1990): 1461+

- Franklin, Benjamin (2008) [1775]. "Journals of the Continental Congress – Franklin's Articles of Confederation; July 21, 1775". The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy. New Haven, CT: Yale University, Lillian Goldman Law Library. Retrieved March 7, 2017. Cited is a digital version of the Journals of the Continental Congress 1774–1779, Vol. II, pp. 195–199, as edited from original records in the Library of Congress by Worthington Chauncey Ford. Primary source.

- Frank Pommersheim (2009). Broken Landscape: Indians, Indian Tribes, and the Constitution. Oxford University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-19-988828-3.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1782). "Notes on the State of Virginia". Revolutionary War and Beyond. Revolutionary War and Beyond. Retrieved 2014-07-14. Primary source.

- Peter S. Onuf (2000). Jefferson's Empire: The Language of American Nationhood. University of Virginia Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8139-2204-1.

- Winthrop D. Jordan (1974). The White Man's Burden: Historical Origins of Racism in the United States. Oxford University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-19-501743-4.

- Francis Paul Prucha (1985). The Indians in American Society: From the Revolutionary War to the Present. University of California Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-520-90884-0.

- Francis Paul Prucha (1997). American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly. University of California Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-520-91916-7.

- James W. Fraser (2016). Between Church and State: Religion and Public Education in a Multicultural America. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4214-2059-2.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1782). "Letter to Governor William H. Harrison". The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. The Pennsylvania State University Libraries. p. 370. Retrieved July 14, 2014. Primary source.

- New York Supplement, New York State Reporter. 146. St. Paul: West Publishing Company. 1909. p. 191.

- "Washington's Address to the Senecas, 1790". uoregon.edu. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Sharon Malinowski; George H. J. Abrams (1995). Notable Native Americans. Gale Research. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-8103-9638-8.

- Mathew Manweller (2012). Chronology of the U.S. Presidency. ABC-CLIO. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-59884-645-4.

- "Fourth Annual Message to Congress (November 6, 1792)". millercenter.org. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia. Archived from the original on February 13, 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- "Seventh Annual Message to Congress (December 8, 1795)". millercenter.org. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- Wayne Moquin; Charles Lincoln Van Doren (1973). Great Documents in American Indian History. Praeger. p. 105.

- Michael Grossberg; Christopher Tomlins (2008). The Cambridge History of Law in America. Cambridge UP. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-521-80305-2.

- James D. St. Clair and William F. Lee. "Defense of Nonintercourse Act Claims: The Requirement of Tribal Existence." Maine Law Review 31. no. 1 (1979): 91+

- "President Jefferson and the Indian Nations". Monticello. Retrieved 2020-07-13.

- Colin G. Calloway (1998). New Worlds for All: Indians, Europeans, and the Remaking of Early America. JHU Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-8018-5959-5.

- Robert W. Tucker; David C. Hendrickson (1992). Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas Jefferson. Oxford University Press. pp. 305–306. ISBN 978-0-19-802276-3.

- Katherine A. Hermes (2008). Michael Grossberg; Christopher Tomlins (eds.). The Cambridge History of Law in America. I, Early America (1580–1815). Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-521-80305-2.

- Thomas Jefferson (June 29, 2017). "From Thomas Jefferson to Handsome Lake, 3 November 1802". Founders Online. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 38, 1 July–12 November 1802, ed. Barbara B. Oberg. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011, pp. 628–631.]

- William Gerald McLoughlin (1992). Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton University Press. pp. xv, 132. ISBN 978-0-691-00627-7.

- "Eighth Annual Message (November 8, 1808) Thomas Jefferson". millercenter.org. University of Virginia. 28 December 2016. Archived from the original on February 13, 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- Robert J. Miller (2006). Native America, Discovered and Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis & Clark, and Manifest Destiny. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-275-99011-4.

- Jason Edward Black (2015). American Indians and the Rhetoric of Removal and Allotment. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-62674-485-1.

- Jay H. Buckley (2008). William Clark: Indian Diplomat. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-8061-3911-1.

There is no doubt that Jefferson wanted to get Indians into debt so that he could lop off their holdings through land cessions.

- Paul R. Bartrop; Steven Leonard Jacobs (2014). Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection [4 volumes]: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. p. 2070. ISBN 978-1-61069-364-6.

- Francis Paul Prucha (2000). Documents of United States Indian Policy. U of Nebraska Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8032-8762-4.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1803). "President Thomas Jefferson to William Henry Harrison, Governor of the Indiana Territory". Retrieved 2009-03-12.

When they withdraw themselves to the culture of a small piece of land, they will perceive how useless to them are their extensive forests, and will be willing to pare them off from time to time in exchange for necessaries for their farms and families. To promote this disposition to exchange lands, which they have to spare and we want, for necessaries, which we have to spare and they want, we shall push our trading uses, and be glad to see the good and influential individuals among them run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop them off by a cession of lands. At our trading houses, too, we mean to sell so low as merely to repay us cost and charges, so as neither to lessen or enlarge our capital. This is what private traders cannot do, for they must gain; they will consequently retire from the competition, and we shall thus get clear of this pest without giving offence or umbrage to the Indians. In this way our settlements will gradually circumscribe and approach the Indians, and they will in time either incorporate with us as citizens of the United States, or remove beyond the Mississippi. The former is certainly the termination of their history most happy for themselves; but, in the whole course of this, it is essential to cultivate their love. As to their fear, we presume that our strength and their weakness is now so visible that they must see we have only to shut our hand to crush them, and that all our liberalities to them proceed from motives of pure humanity only. Should any tribe be foolhardy enough to take up the hatchet at any time, the seizing the whole country of that tribe, and driving them across the Mississippi, as the only condition of peace, would be an example to others, and a furtherance of our final consolidation.

Primary source. - Texts by or to Thomas Jefferson (2005). "Excerpt from President Jefferson's Private Letter to William Henry Harrison, Governor of the Indiana Territory February 27, 1803". adl.org. Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original (Modern English Collection, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library) on June 1, 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- William Gerald McLoughlin (1992). Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton University Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-691-00627-7.

- Charles Joseph Kappler, ed. (1903). Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. 2. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 124.

- William G. McLoughlin (Spring 1981). "Experiment in Cherokee Citizenship, 1817–1829". American Quarterly. 33 (1): 3–25. doi:10.2307/2712531. JSTOR 2712531.

- John K. Mahon (1991). History of the Second Seminole War, 1835–1842. University Presses of Florida. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8130-1097-7.

- Paul E. Teed (2006). John Quincy Adams: Yankee Nationalist. Nova Publishers. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-59454-797-3.

- Kathy Warnes (2016). "Cherokee Nation vs, Georgia, Forced Removal of Indian Tribes (1831)". In Steven Chermak; Frankie Y. Bailey (eds.). Crimes of the Centuries: Notorious Crimes, Criminals, and Criminal Trials in American History [3 volumes] Notorious Crimes, Criminals, and Criminal Trials in American History. ABC-CLIO. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-61069-594-7.

- Francis Paul Prucha (1995). The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians. U of Nebraska Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-8032-8734-1.

- John K. Mahon (1991). History of the Second Seminole War, 1835–1842. University Presses of Florida. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8130-1097-7.

- Sturgis, Amy (2007). The Trail of Tears and Indian Removal. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 135. ISBN 031333658X.

- Sturgis, Amy (2007). The Trail of Tears and Indian Removal. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 031333658X.

- Satz, Ronald N. (1975). American Indian Policy in the Jacksonian Era. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-8061-3432-1.

- Perdue, Theda (2016). The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents (3rd ed.). Boston: Bedford/St.Martin's. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-319-04902-7.

- Faiman-Silva, Sandra (1997). Choctaws at the Crossroads. University of Nebraska Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-8032-2001-4.

- Perdue, Theda (2016). The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents (3rd ed.). Boston: Bedford/St.Martin's. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-319-04902-7.

- Ronald N. Satz; Laura Apfelbeck (1996). Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin's Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-299-93022-6.

- Kane, Sharyn & Keeton, Richard (1994). "As Long as Grass Grows [Ch. 11]". Fort Benning: The Land and the People. Fort Benning, GA and Tallahassee, FL: U.S. Army Infantry Center, Directorate of Public Works, Environmental Management Division, and National Park Service, Southeast Archaeological Center. pp. 95–104. ISBN 978-0-8061-1172-8. OCLC 39804148. Archived from the original on August 17, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2017.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) The work is also available from the U.S. Army, as a Benning History/Fort Benning the Land and the People.pdf PDF.

- Chris J. Magoc (2015). Imperialism and Expansionism in American History: A Social, Political, and Cultural Encyclopedia and Document Collection [4 volumes]: A Social, Political, and Cultural Encyclopedia and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. p. 400. ISBN 978-1-61069-430-8.

- Faiman-Silva, Sandra (1997). Choctaws at the Crossroads. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8032-6902-6. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Thomas Ruys Smith (2007). River of Dreams: Imagining the Mississippi Before Mark Twain. Louisiana State University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8071-4307-0.

- George Wilson Pierson (1938). Tocqueville in America. Johns Hopkins Press. p. 598. ISBN 978-0-8018-5506-1.

- Laurence French (2007). Legislating Indian Country: Significant Milestones in Transforming Tribalism. Peter Lang. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8204-8844-8.

- Amy H. Sturgis (2007). The Trail of Tears and Indian Removal. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-0-313-33658-4.

- Russell Thornton (1992). The Cherokees: A Population History. U of Nebraska Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8032-9410-3.

- John A. Andrew, III (2007). From Revivals to Removal: Jeremiah Evarts, the Cherokee Nation, and the Search for the Soul of America. University of Georgia Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-8203-3121-8.

- Frederick E. Hoxie (1984). A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880–1920. U of Nebraska Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-8032-7327-6.

The court has bestowed its best attention on this question, and, after mature deliberation, the majority is of the opinion that an Indian tribe or nation within the United States is not a foreign state in the sense of the constitution, and cannot maintain an action in the courts of the United States.

- Charles F. Hobson (2012). The Papers of John Marshall: Vol XII: Correspondence, Papers, and Selected Judicial Opinions, January 1831 – July 1835, with Addendum, June 1783 – January 1829. UNC Press Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8078-3885-3.

- Henry Thompson Malone (2010). Cherokees of the Old South: A People in Transition. University of Georgia Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-8203-3542-1.

- Robert V. Remini (2013). Andrew Jackson: The Course of American Freedom, 1822-1832. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-1-4214-1329-7.

- "America's Indian Removal Policies: Tales & Trails of Betrayal Indian Policy During Andrew Jackson's Presidency (1829–1837)" (PDF). civics.sites.unc.edu. University of North Carolina. May 2012. p. 15. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Ronald N. Satz (1974). American Indian Policy in the Jacksonian Era. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8061-3432-1.

- Brian Black; Donna L. Lybecker (2008). Great Debates in American Environmental History. Greenwood Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-313-33931-8.

- Patricia Riles Wickman (2006). Osceola's Legacy. University of Alabama Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8173-5332-2.

- Spencer Tucker; James R. Arnold; Roberta Wiener (2011). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 719. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8.

- Haveman, Christopher D. Rivers of sand : Creek Indian emigration, relocation, and ethnic cleansing in the American South. Removal of the Creek Indians from the Southeast: University of Nebraska. pp. 200–233. ISBN 978-0-8032-7392-4.

- Jesse Clifton Burt; Robert B. Ferguson (1973). Indians of the Southeast: Then and Now. Abingdon Press. pp. 170–173. ISBN 978-0-687-18793-5.

- Thomas Dionysius Clark (1996). The Old Southwest, 1795-1830: Frontiers in Conflict. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8061-2836-8.

- James P. Pate (2009). "Chickasaw The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture". okhistory.org. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- Arrell M. Gibson (21 November 2012). The Chickasaws. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-8061-8864-5.

- Blue Clark (2012). Indian Tribes of Oklahoma: A Guide. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8061-8461-6.

- James Minahan (2013). Ethnic Groups of the Americas: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-61069-163-5.

- Arrell Morgan Gibson (1984). The History of Oklahoma. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8061-1883-3.

- Rusty Williams (20 May 2016). The Red River Bridge War: A Texas-Oklahoma Border Battle. Texas A&M University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-62349-406-3.

- Christopher Arris Oakley (1 January 2005). Keeping the Circle: American Indian Identity in Eastern North Carolina, 1885-2004. U of Nebraska Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8032-5069-7.

- Gary Clayton Anderson (10 March 2014). Ethnic Cleansing and the Indian: The Crime That Should Haunt America. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-8061-4508-2.

- Mikaela M. Adams (15 September 2016). Who Belongs?: Race, Resources, and Tribal Citizenship in the Native South. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-061947-3.

- John R. Finger (1984). The Eastern Band of Cherokees, 1819-1900. Univ. of Tennessee Press. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-87049-410-9.

- Jessica Joyce Christie (2009). Landscapes of Origin in the Americas: Creation Narratives Linking Ancient Places and Present Communities. University of Alabama Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8173-5560-9.

- Benjamin A. Steere (2017). "Collaborative Archaeology as a Tool For Preserving Sacred Sites in the Cherokee Heartland". In Fausto Sarmiento; Sarah Hitchner (eds.). Indigeneity and the Sacred: Indigenous Revival and the Conservation of Sacred Natural Sites in the Americas. Berghahn Books. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-78533-397-2.

- Samuel J. Wells (2010). "Introduction". In Samuel J. Wells; Roseanna Tubby (eds.). After Removal: The Choctaw in Mississippi. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. ix. ISBN 978-1-61703-084-0.

- Daniel F. Littlefield, Jr.; James W. Parins, eds. (2011). "Alabama and Indian Removal". Encyclopedia of American Indian Removal. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-313-36041-1.

- Brent Richards Weisman (1989). Like Beads on a String: A Culture History of the Seminole Indians in North Peninsular Florida. University of Alabama Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8173-0411-9.

- David Heidler; Jeanne Heidler (1 February 2003). Old Hickory's War: Andrew Jackson and the Quest for Empire. LSU Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8071-2867-1.

- William C. Sturtevant (2008). Handbook of North American Indians. Government Printing Office. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-16-080388-8.

- James F. Barnett (4 April 2012). Mississippi's American Indians. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-61703-246-2.

- William C. Sturtevant (2008). Handbook of North American Indians. Government Printing Office. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-16-080388-8.

- Daniel F. Littlefield, Jr.; James W. Parins (2011). Encyclopedia of American Indian Removal. ABC-CLIO. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-313-36041-1.

- Keith S. Hébert (January 18, 2017). "Poarch Band of Creek Indians". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Linda S. Parker (1996). Native American Estate: The Struggle Over Indian and Hawaiian Lands. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-8248-1807-4.

- Edward S. Curtis (1930). The North American Indian. Volume 19 – The Indians of Oklahoma. The Wichita. The southern Cheyenne. The Oto. The Comanche. The Peyote cult. Edward S. Curtis. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7426-9819-2.

- R. David Edmunds (1978). The Potawatomis: Keepers of the Fire. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-8061-2069-0.

- Michael D. Green (2008). ""We Dance in Opposite Directions": Mesquakie (Fox) Separatism from the Sac and Fox Tribe*". In Marvin Bergman (ed.). Iowa History Reader. University of Iowa Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-60938-011-3.

- Lewis, James (2000). "The Black Hawk War of 1832". DeKalb, IL: Abraham Lincoln Digitization Project, Northern Illinois University. p. 2D. Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Jay P. Kinney (1975). A Continent Lost, a Civilization Won: Indian Land Tenure in America. Octagon Books. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-374-94576-3.

- Kathleen Tigerman (2006). Wisconsin Indian Literature: Anthology of Native Voices. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-299-22064-8.

- John P. Bowes (2014). "American Indian Removal beyond the Removal Act". Wicazo Sa Review. 1 (1): 65. doi:10.5749/natiindistudj.1.1.0065. ISSN 0749-6427.

- Laurence M. Hauptman (2014). In the Shadow of Kinzua: The Seneca Nation of Indians since World War II. Syracuse University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-8156-5238-0.

- John P. Bowes (2011). "Ogden Land Company". In Daniel F. Littlefield, Jr. (ed.). Encyclopedia of American Indian Removal. James W. Parins. ABC-CLIO. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-313-36041-1.

- Margaret Wooster (2009). Living Waters: Reading the Rivers of the Lower Great Lakes. SUNY Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-7914-7712-0.

- Grant Foreman (1972). Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 47, note 10 (1830 census). ISBN 978-0-8061-1172-8.

- Several thousand more emigrated West from 1844 to 1849; Foreman, pp. 103–4.

- Foreman, p. 111 (1832 census).

- Remini 2001, p. 272.

- Russell Thornton (1992). "The Demography of the Trail of Tears Period: A New Estimate of Cherokee Population Losses". In William L. Anderson (ed.). Cherokee Removal: Before and After. University of Georgia Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8203-1482-2.

- Francis Paul Prucha (1 January 1995). The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians. U of Nebraska Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-8032-8734-1.

- Anthony Wallace; Eric Foner (July 1993). The Long, Bitter Trail: Andrew Jackson and the Indians. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-0-8090-1552-8.

- Wilentz, Sean (2006). The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 324. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Bartrop Paul R. & Jacobs, Steven Leonard (2014). Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. p. 2070. ISBN 978-1-61069-364-6.

- Howard Zinn (2012). Howard Zinn Speaks: Collected Speeches 1963–2009. Haymarket Books. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-60846-228-5.

- Prucha, Francis Paul (1969). "Andrew Jackson's Indian Policy: A Reassessment". Journal of American History. 56 (3): 527–539. doi:10.2307/1904204. JSTOR 1904204.

- Howard Zinn (12 August 2015). A People's History of the United States: 1492–Present. Routledge. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-317-32530-7.

- Barbara Alice Mann (2009). The Tainted Gift: The Disease Method of Frontier Expansion. ABC-CLIO. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-313-35338-3.

Further reading

- Black, Jason Edward (2006). US Governmental and Native Voices in the Nineteenth Century: Rhetoric in the Removal and Allotment of American Indians. (PhD dissertation), College Park, MD: University of Maryland. See, for instance, the bibliography on pp. 571–615.

- Ehle, John (1988). Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation. New York, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 038523953X.

- Jahoda, Gloria (1975). The Trail of Tears: The Story of the American Indian Removals 1813–1855. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-014871-5.

- Saunt, Claudio (2020). Unworthy republic: the dispossession of Native Americans and the road to Indian territory (First ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-60985-1.

- Strickland, William M. (1982). Southern Speech Communication Journal 47(3): 292–309.