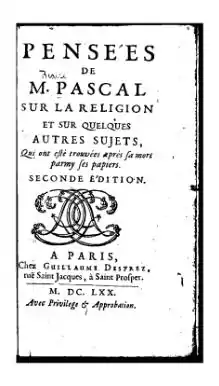

Pensées

The Pensées ("Thoughts") is a collection of fragments written by the French 17th-century philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal. Pascal's religious conversion led him into a life of asceticism, and the Pensées was in many ways his life's work.[1] It represented Pascal's defense of the Christian religion, and the concept of "Pascal's wager" stems from a portion of this work.[2]

Publication history

The Pensées is the name given posthumously to fragments that Pascal had been preparing for an apology for Christianity, which was never completed. That envisioned work is often referred to as the Apology for the Christian Religion, although Pascal never used that title.[3]

Although the Pensées appears to consist of ideas and jottings, some of which are incomplete, it is believed that Pascal had, prior to his death in 1662, already planned out the order of the book and had begun the task of cutting and pasting his draft notes into a coherent form. His task incomplete, subsequent editors have disagreed on the order, if any, in which his writings should be read.[4] Those responsible for his effects, failing to recognize the basic structure of the work, handed them over to be edited, and they were published in 1670.[5]The first English translation was made in 1688 by John Walker.[6] Another English translation by W. F. Trotter was published in 1958.[7] The proper order of the Pensées is heavily disputed.[2]

Several attempts have been made to arrange the notes systematically; notable editions include those of Léon Brunschvicg, Jacques Chevalier, Louis Lafuma and (more recently) Philippe Sellier. Although Brunschvicg tried to classify the posthumous fragments according to themes, recent research has prompted Sellier to choose entirely different classifications, as Pascal often examined the same event or example through many different lenses. Also noteworthy is the monumental edition of Pascal's Œuvres complètes (1964–1992), which is known as the Tercentenary Edition and was realized by Jean Mesnard;[8] although still incomplete, this edition reviews the dating, history and critical bibliography of each of Pascal's texts.[9]

References

- Copleston, Frederick Charles (1958). History of Philosophy: Descartes to Leibniz. p. 155. ISBN 0809100681.

- Hammond, Nicholas (2000). "Blaise Pascal". In Hastings; et al. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought. p. 518. ISBN 9780198600244.

- Krailsheimer, A.J. (1995). "Introduction". Pensées. Penguin. p. xviii. ISBN 0140446451.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blaise Pascal, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (accessed 2010-03-11)

- Krailsheimer 1995, p. x.

- Daston, Lorraine. Classical Probability in the Enlightenment. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- The Project Gutenberg EBook of Pascal's Pensées, by Blaise Pascal (accessed 2014-10-06)

- Jouslin, Olivier (2007). "Rien ne nous plaît que le combat": la campagne des Provinciales de Pascal. 1. Presses Univ Blaise Pascal. p. 781.

- See in particular various works by Laurent Thirouin, for example “Les premières liasses des Pensées : architecture et signification”, XVIIe siècle, n°177 (spécial Pascal), oct./déc. 1992, pp. 451-468 or “Le cycle du divertissement, dans les liasses classées”, Giornata di Studi Francesi, “Les Pensées de Pascal : du dessein à l’édition”, Rome, Université LUMSA, 11-12 October 2002.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Pensees at Project Gutenberg

- Pensees in French

- Etext version of the Pensées

- 1671 edition with old French spelling (PDF ebook)

(in French) Livres audio mp3 gratuits 'Pensée n° XXIII : Grandeur de l'homme' de Blaise Pascal - (Association Audiocité).

(in French) Livres audio mp3 gratuits 'Pensée n° XXIII : Grandeur de l'homme' de Blaise Pascal - (Association Audiocité).