People's Rights Party

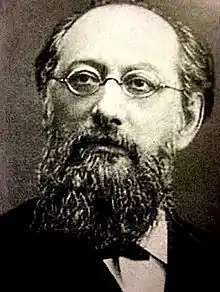

The People's Rights Party (Russian: Партия Народного Права), was a radical constitutionalist political party established in Tsarist Russia in 1893. The group's political leader was the agrarian populist Mark Natanson and its ideological leading light was the literary critic and public affairs commentator N.K. Mikhailovsky.

People's Rights Party (Партия Народного Права) | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Mark Natanson |

| Founded | Summer 1893 |

| Dissolved | April 1894 |

| Headquarters | Orël, Russian Empire |

| Ideology | Constitutionalism Agrarian socialism |

While the People's Rights Party was small and short-lived owing to repression by the Tsarist political police, it has been remembered for its transitional place between the 19th Century Russian populist movement and a key 20th Century political organization, the Socialist Revolutionary Party (PSR).

History

Background

At the end of the 1870s the Russian agrarian populist underground political party Zemlya i Volya ("Land and Liberty") split over the question of tactics between those who advocated direct education and agitation among the peasantry and urban workers and the maintenance of student study circles and those who advocated the use of terrorism against high officials in the Tsarist regime — up to and including the Tsar himself — in order to create conditions for an instantaneous revolutionary upheaval.

Those who advocated the agitational approach organized as Chërnyi Peredel ("Black Repartition") and were quickly arrested or driven into exile after easily being identified by the police. Those pursuing revolutionary terrorism formed their own group, Narodnaya Volya ("People's Will") and managed to realize a primary objective when in March 1881 they successfully assassinated Tsar Alexander II with a bomb. No revolution followed, however, only harsh repression ending in the execution of a number of prominent Narodnaya Volya members and the obliteration of the underground organization by 1884.

Following the annihilation of Narodnaya Volya there followed nearly a decade of political disillusionment and inactivity among the Russian revolutionary intelligentsia.[1] Even the devastating Famine of 1891-1892 did not stir the peasantry to revolt against the Tsarist regime — although the crisis did play a part in moving urban intellectuals in Russia to resume political activity in an effort to bring about an end to autocratic rule.[1] One of the leading manifestations of this new political offensive was the establishment of the People's Rights Party (Partiya Narodnogo Prava) in 1893.

Formation

The People's Rights Party was founded in the summer of 1893 in the Russian city of Saratov.[2] The group was composed of a small core of active members but influenced a much broader network of sympathizers and supporters.[3] Leader of the party was veteran agrarian socialist Mark Natanson (party name: Bobrov) and two of his personal friends and political co-thinkers, Nikolai Tyutchev and Osip Aptekman, none of whom had previously been members of Narodnaya Volya.[4]

These were joined in sympathy, albeit not in formal membership, by agrarian populist Nikolai Mikhailovsky and a group of his associates from the journal Russkoe Bogatstvo (Russian Riches), V. G. Korolenko, N. F. Anensky, and A. V . Peshekonov.[3] The group's leading supporter in Moscow was former study circle leader A. I. Ryazanov, while non-party sympathizers counted among their numbers the historian V.Ia. Bogucharsky.[5]

An illegal organization in Russia, the People's Rights Party established an underground printing press in Smolensk, by means of which it produced its publications.[6] Owing to limited circulation only two of the party's publications have survived — the party's program and a single pamphlet, Nasushchnyi Vopros (The Urgent Question).[7]

Political program

The People's Rights Party advocated that a broad alliance of radicals should be cobbled together around a single central goal, the overthrow of Tsarist autocracy, with all controversial goals and objectives set aside until that fundamental task was realized.[6]

The group sought to make a break from what it called "the decayed ideas of populism," efforts to extend culture, and petty political reforms, and to make a decisive break with "the condescending worship of the mythical 'people' (narod)" and to concentrate instead upon "the struggle for political liberty" as the means to overthrow absolutism.[8]

In the estimation of historian Shmuel Galai, the programmatic originality of the People's Rights Party lay not in its setting down of political liberty as a goal of the organization — which had been stated as an objective by other radical populist organizations — but its intimation that the adoption of the methods of liberal democracy would be the means to that end as well.[9] Citing the group's program, Galai has asserted that "for the first time in the annals of Russian parties, it declared organized public opinion to be the main weapon in the struggle against autocracy," in contradistinction to peasant revolt, general strike, or terror.[9]

The People's Rights Party's program called specifically for adoption for all of policies extending "the rights of citizen and man," which were to include:

- Representative government on the basis of universal suffrage;

- Freedom of religious belief;

- Independence of the courts of justice;

- Freedom of meeting and association;

- Inviolability of the individual and of his rights as a man;

- The right of self-determination for all the nationalities entering into [the Russian Empire][10]

Dissolution and legacy

The Okhrana, the Tsarist secret police, had been aware of the activities of the ostensibly underground People's Rights Party very nearly from its beginning but had allowed the party to continue its activities until it could extract all the information possible about its participants and sympathizers.[11] The publication of the group's program, written in the form of a manifesto, on February 19, 1894, escalated the situation from the perspective of the authorities.[11] A coordinated raid was organized and executed on the morning of April 21, 1894, with simultaneous arrests made in five cities, including the group's headquarters city of Orël, St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kharkov, as well as Smolensk, location of the party's secret press.[11] A total of 52 arrests were made as part of the operation — a majority of the group's formal members.[11]

Mark Natanson, the head of the party, was among those arrested, with the resulting sentence consigning him to ten years of administrative exile in Siberia.[12] Other top leaders arrested at the time included N.S. Tyutchev, A.V. Peshekhonov, and future leader of the Socialist Revolutionary Party Victor Chernov.[11] Those who were not arrested immediately halted their illegal political activity or fled the country.[11] The organization was effectively destroyed with the one single blow.

The party proved to be a political failure owing to its inability to conduct its activities in public and small size, combined with its extremely short lifespan.[13] Nevertheless, the group has been regarded by intellectual historians as influential as a watershed in the process of demythologizing belief in the transformative essence of the peasant masses and in its abnegation of traditional Russian rejection of the norms of western constitutionalism as both a vehicle and a goal for change.[13]

Former members of the People's Rights Party would re-emerge as top leaders of the constitutionalist Union of Liberation or would join the Socialist Revolution Party after its organization in 1902.[11]

Footnotes

- Shmuel Galai, The Liberation Movement in Russia, 1900-1905. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1973; pg. 59.

- O.V. Aptekman, "Partiia Narodnogo Prava: Vospominaniia" (People's Rights Party: Reminiscences). Byloye, no. 7 (1907), pp. 196-197; cited in Galai, The Liberation Movement in Russia, pg. 59.

- Galai, The Liberation Movement in Russia, pg. 60.

- Galai notes that Natanson and Tyutchev had already been jailed before the establishment of Narodnaya Volya, while Aptekman was a former member Chërnyi Peredel. Galai, The Liberation Movement in Russia, pg. 60.

- Galai, The Liberation Movement in Russia, pp. 61-62.

- Jonathan Frankel, Vladimir Akimov on the Dilemmas of Russian Marxism, 1895-1903. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1969; pg. 235.

- Aptekman, Partiia Narodnogo Prava, pp. 199-201; cited in Galai, The Liberation Movement in Russia, pg. 61.

- A.I. Bogdanovich, Nasuschchnyi Vopros, quoted in Aptekman, Partiia Narodnogo Prava, pg. 201; cited by Galai, The Liberation Movement in Russia, pp. 63-64.

- Galai, The Liberation Movement in Russia, pg. 64.

- Program of the People's Rights Party, quoted in Galai, 'The Liberation Movement in Russia, pp. 64-65.

- Galai, The Liberation Movement in Russia, pg. 65.

- Mandred Hildermeier, The Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party Before the First World War. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000; pg. 382.

- Klaus Frölich, The Emergence of Russian Constitutionalism, 1900-1904. Amsterdam: Institute of Social History, 1981; pg. ???

Further reading

- O.V. Aptekman, "Partiia Narodnogo Prava: Vospominaniia" (People's Rights Party: Reminiscences). Byloye, no. 7 (1907), pp. 117–206.

- James H. Billington, Mikhailovsky and Russian Populism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1958.

- Klaus Frölich, The Emergence of Russian Constitutionalism, 1900-1904. Amsterdam: Institute of Social History, 1981.

- Shmuel Galai, The Liberation Movement in Russia, 1900-1905. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1973.

- "A Revolutionary Revival in Russia," Literary Digest, vol. 10, no. 20 (March 16, 1895), pp. 22–23.

- "The People's Rights Party in Russia, a Liberal Association Said..." The Spectator, whole no. 3,477 (Feb. 16, 1895), pg. 3.