Perfect Blue

Perfect Blue (Japanese: パーフェクトブルー, Hepburn: Pāfekuto Burū) is a 1997 Japanese adult animated psychological thriller film[4][5] directed by Satoshi Kon[6] and written by Sadayuki Murai. It is based on the novel Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis (パーフェクト・ブルー 完全変態, Pāfekuto Burū: Kanzen Hentai) by Yoshikazu Takeuchi. The film features the voices of Junko Iwao, Rica Matsumoto, Shiho Niiyama, Masaaki Okura, Shinpachi Tsuji, and Emiko Furukawa.

| Perfect Blue | |

|---|---|

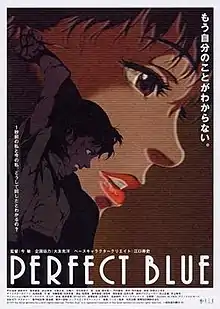

Japanese theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Satoshi Kon |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | Sadayuki Murai |

| Based on | Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis by Yoshikazu Takeuchi |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Masahiro Ikumi |

| Cinematography | Hisao Shirai |

| Edited by | Harutoshi Ogata |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Rex Entertainment |

Release date |

|

Running time | 81 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Budget | ¥90 million[1] (US$830,442)[2] |

| Box office | $768,050 (US & UK only)[3] |

The film follows Mima Kirigoe, a member of a Japanese idol group, who retires from music to pursue an acting career. As she becomes a victim of stalking, gruesome murders begin to occur, and Mima starts to lose her grip on reality. Like much of Kon's later work, such as Paprika, the film deals with the blurring of the lines between fantasy and reality in contemporary Japan.[7]

Plot

Mima Kirigoe, a member of a mildly-successful J-pop group named "CHAM!", decides to leave the group to become a full-time actress. She is joined by her long-time manager and former pop-idol Rumi Hidaka, and her agent Tadokoro. Mima's first job is a minor role in a television detective drama called "Double Bind". Some of her fans are upset by her change in career and persona from a squeaky-clean and innocent teen girl, including a terrifying-looking male stalker who goes by the alias "Me-Mania". Mima receives an anonymous fax calling her a traitor, and even a letter bomb that injures Tadokoro. Following directions from a fan letter, Mima discovers a website called "Mima's Room" containing public diary entries written from her perspective, and which accurately discuss her daily life and thoughts in intimate and exacting detail. Mima confides in Rumi about the site, but is advised to ignore it.

Tadokoro lobbies the producers of Double Bind, and succeeds in securing Mima a larger part; however, this involves her character being raped in a strip club. Rumi is distressed by the scene and warns Mima that it will irreversibly change her public image, but Mima accepts the role despite her own misgivings. Though it is apparent that Mima tries her best and is treated professionally, the atmosphere and experience of filming the rape scene is traumatic. Between the ongoing stresses of filming Double Bind, her lingering regret over leaving CHAM!, her paranoia of being stalked, and her increasing obsession with "Mima's Room", Mima begins to suffer from psychosis: in particular, struggling to distinguish real life from her work in show business.

Several people who had been involved in the so-called "tarnishing" of Mima's reputation are murdered. Mima finds evidence which makes her appear to be the prime suspect, and her mental instability makes her doubt her own memories and innocence. Mima manages to finish shooting Double Bind, the final scene of which reveals that her character killed and assumed the identity of her beloved sister due to trauma-induced dissociative identity disorder. After the rest of the filming staff have left the studio, Me-Mania attempts to kill her under emailed instructions from "the real Mima" to "eliminate the impostor", but Mima knocks him unconscious with a hammer in self-defense and flees. Later, Me-Mania attacks Tadokoro, and in the struggle they end up killing each other.

Mima is found backstage by Rumi and taken back to Rumi's home, only to discover that Rumi was the culprit behind "Mima's Room", the serial murders, and the folie à deux that manipulated and scapegoated Me-Mania. Sometime in the past, Rumi developed a second personality who vicariously believed herself to be the "real Mima" (her pure-hearted and forever-young idol persona), using information from Mima's confiding in her as the basis for "Mima's Room". Rumi's "Mima" personality attempts to murder Mima to preserve "her" pristine image forever, and following a chase through the city, Mima incapacitates Rumi in self-defense and saves her from being killed by an oncoming truck.

Some time later, Mima becomes a well-known actress following the critical success of her performance in Double Bind and Rumi is sent to a psychiatric hospital with her "Mima" personality dominant. The movie ends with Mima driving off and looks at herself in the rear view mirror saying “No, I’m the real thing.”

Cast

| Character | Japanese | English[8] |

|---|---|---|

| Mima Kirigoe (霧越 未麻, Kirigoe Mima) | Junko Iwao | Ruby Marlowe[9] |

| Rumi (ルミ) | Rica Matsumoto | Wendee Lee[10] |

| Tadokoro (田所) | Shinpachi Tsuji | Gil Starberry |

| Mamoru Uchida (Me-Mania) (内田 守, Uchida Mamoru) | Masaaki Ōkura | Bob Marx[11] |

| Tejima (手嶋) | Yōsuke Akimoto | Steve Bulen |

| Takao Shibuya (渋谷 貴雄, Shibuya Takao) | Yoku Shioya | Jimmy Theodore |

| Sakuragi (桜木) | Hideyuki Hori | Sparky Thornton[12] |

| Eri Ochiai (落合 恵理, Ochiai Eri) | Emi Shinohara | Lia Sargent |

| Murano (村野) | Masashi Ebara | Jamieson Price |

| Director (監督, Kantoku) | Kiyoyuki Yanada | Richard Plantagenet |

| Yada (矢田) | Tōru Furusawa | – |

| Yukiko (雪子) | Emiko Furukawa | Bambi Darro |

| Rei (レイ) | Shiho Niiyama | Melissa Williamson |

| Tadashi Doi (土居 正, Doi Tadashi) | Akio Suyama | – |

| Cham Manager | – | Dylan Tully |

The following actors in the English adaptation are listed in the credits without specification to their respective roles: James Lyon, Frank Buck, David Lucas, Elliot Reynolds, Kermit Beachwood, Sam Strong, Carol Stanzione, Ty Webb, Billy Regan, Dari Mackenzie, George C. Cole, Syd Fontana, Sven Nosgard, Bob Marx, Devon Michaels, Robert Wicks and Mattie Rando.[13]

Production

Originally, the film was supposed to be a live action direct to video series, but after the Kobe earthquake of 1995 damaged the production studio, the budget for the film was reduced to an original video animation. Katsuhiro Otomo was credited as "Special Supervisor" to help the film sell abroad, and as a result, the film was screened in many film festivals around the world. While touring the world it received a fair amount of acclaim, jump-starting Kon's career as a filmmaker.[14]

Kon and Murai did not think that the original novel would make a good film and asked if they could change the contents. This change was approved so long as they kept a few of the original concepts from the novel. A live-action film adaptation of the novel, Perfect Blue: Yume Nara Samete, was later made and released in 2002. This version was directed by Toshiki Satō from a screenplay by Shinji Imaoka and Masahiro Kobayashi.[15]

Themes and analysis

Susan Napier uses her experience to analyze the film, stating that "Perfect Blue announces its preoccupation with perception, identity, voyeurism, and performance – especially in relation to the female – right from its opening sequence. The perception of reality cannot be trusted, with the visual set up only to not be reality, especially as the psychodrama heights towards the climax."[14] Napier also sees themes related to pop idols and their performances as impacting the gaze and the issue of their roles. Mima's madness results from her own subjectivity and attacks on her identity. The ties to Alfred Hitchcock's work is broken with the murder of her male controllers.[14] Otaku described the film as "critique of the consumer society of contemporary Japan."[14][Note 1]

Release

Perfect Blue premiered on August 5, 1997, at the Fantasia Film Festival in Montreal, Canada,[16] and had its general release in Japan on February 28, 1998.[17]

The film was also released on UMD by Anchor Bay Entertainment on December 6, 2005.[18] It featured the film in widescreen, leaving the film kept within black bars on the PSP's 16:9 screen. This release also contains no special features and only the English audio track. The film was released on Blu-ray and DVD in Region B by Anime Limited in 2013.[19][20] In the U.S., Perfect Blue aired on the Encore cable television network and was featured by the Sci Fi Channel on December 10, 2007, as part of its Ani-Monday block. In Australia, Perfect Blue aired on the SBS Television Network on April 12, 2008, and previously sometime in mid 2007 in a similar timeslot.

The film had a theatrical re-release in the United States by GKIDS on September 6 and 10, 2018, with both English dubbed and subtitled screenings.[21] GKIDS and Shout! Factory released the film on Blu-ray Disc in North America on March 26, 2019.[22]

Reception

The film was well received critically in the festival circuit, winning awards at the 1997 Fantasia Festival in Montréal, and Fantasporto Film Festival in Portugal.

Critical response in the United States upon its theatrical release was also positive.[23] As of October 2020, the film had an 80% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 44 reviews, with an average score of 7.19/10. The consensus stated, "Perfect Blue is overstylized, but its core mystery is always compelling, as are the visual theatrics."[24] Time included the film on its Top 5 Anime film list,[25] Total Film ranked Perfect Blue twenty-fifth on their list of greatest animated films,[26] and /Film named it the scariest animated film ever.[27] It also made the list for Entertainment Weekly's best movies never seen from 1991–2011.[28]

Dennis Harvey of Variety wrote that while the film "ultimately disappoints with its just-middling tension and underdeveloped scenario, it still holds attention by trying something different for the genre".[4] Hoai-Tran Bui of /Film called Perfect Blue "deeply violent, both physically and emotionally", writing that "this is a film that will leave you with profound psychological scars, and the feeling that you want to take a long, long shower".[27] Bob Graham of the San Francisco Chronicle noted the film's ability to "take the thriller, media fascination, psychological insight and pop culture and stand them all on their heads" via its "knowing, adult view of what seems to be a young-teenage paradise."[29] Writing for Anime News Network, reviewer Tim Henderson described the film as "a dark, sophisticated psychological thriller" with its effect of "over-obsession funneled through early Internet culture" and produces a "reminder of how much celebrity fandom has evolved in only a decade".[30] Reviewing the 2019 GKIDS Blu-Ray release, Neil Lumbard of Blu-Ray.com heralded Perfect Blue as "one of the greatest anime films of all time" and "a must-see masterpiece that helped to pave the way for more complex anime films to follow,"[31] while Chris Beveridge of The Fandom Post noted "this is not a film one can watch often overall, nor should you, but when you settle into it you put everything else away, turn down the lights, and savor an excellent piece of filmmaking."[32]

Legacy

Madonna incorporated clips from the film into a remix of her song "What It Feels Like for a Girl" as a video interlude during her Drowned World Tour in 2001.[33][34]

American filmmaker Darren Aronofsky acknowledged the similarities in his 2010 film Black Swan, but denied that Black Swan was inspired by Perfect Blue; his previous film Requiem for a Dream features a remake of a scene from Perfect Blue.[35][36] A re-issued blog entry mentioned Aronofsky's film Requiem for a Dream as being among Kon's list of films he viewed for 2010.[37] In addition, Kon blogged about his meeting with Aronofsky in 2001.[38]

Other media

Seven Seas Entertainment has licensed the English-language publication rights for the original Perfect Blue stories Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis and Perfect Blue: Awaken from a Dream for release in 2017 and 2018, respectively.[39]

Notes

- Reference to the quote is provided by Napier as: Jay, "Satoshi Kon", Otaku (May/June 2003):22

References

- "パーフェクトブルー戦記1 発端". Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- "Official exchange rate (LCU per US$, period average)". World Bank. 1998. Archived from the original on January 27, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- "Pâfekuto burû (1999) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- Dennis Harvey (October 31, 1999). "Film Review: "Perfect Blue"". Variety. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- Paul Chapman (August 9, 2018). "Satoshi Kon's Psychological Thriller "Perfect Blue" Heads to U.S. Theaters". Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- Crow, Jonathan. "Perfect Blue". AllMovie. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "Satoshi Kon, Anime's Dream Weaver". Washington Post. June 15, 2007. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- Patten, Fred (2005). Beck, Jerry (ed.). The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. p. 190. ISBN 9781569762226.

- Interview with English Mima (DVD). Manga Entertainment. 2000.

- Interview with English Rumi (DVD). Manga Entertainment. 2000.

- Interview with Mr. Me-Mania (DVD). Manga Entertainment. 2000.

- "Original Animation". kirkthornton.com. Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- A Perfect Blue Day (DVD). Manga Entertainment. 2000. – closing credits

- Napier, Susan J. (2006). "'Excuse Me, Who Are You?': Performance, the Gaze, and the Female in the Works of Kon Satoshi". In Brown, Steven T. (ed.). Cinema Anime: Critical Engagements with Japanese Animation. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-8308-4. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- "夢なら醒めて…". Japanese Cinema Database. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- "Perfect Blue" (PDF). Fantasia Film Festival. p. 64. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- Kon, Satoshi (August 5, 2015). Art of Satoshi Kon. New York City: Dark Horse Comics. p. 124.

- "PSP Perfect Blue". Archived from the original on January 25, 2006. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- Hurtado, Josh (March 2, 2014). "Now on Blu-ray: PERFECT BLUE Gets Some Much Needed Attention From Anime Ltd. (UK)". Screen Anarchy. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- O'Neill, Phelim (November 23, 2013). "Perfect Blue, out this week on DVD & Blu-ray". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- Mateo, Alex (August 3, 2018). "Fandango Lists Fathom Events Screenings of Perfect Blue in U.S." Anime News Network. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- "Perfect Blue Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- "Perfect Blue". Animerica. April 7, 2000. Archived from the original on June 13, 2004.

- "Perfect Blue". Rotten Tomatoes. Los Angeles, California: Fandango Media. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- "5 Top Anime Movies on DVD". Time. July 31, 2005. Archived from the original on January 13, 2008.

- Kinnear, Simon. "50 Greatest Animated Movies". Total Film. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- Hoai-Tran Bui (October 26, 2018). "Ranking The 13 Scariest Animated Movies Ever". /Film. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- "50 Best Movies You've Never Seen". Entertainment Weekly's. July 16, 2012. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- Graham, Bob (October 15, 1999). "Animated Blue Has a Surreal Twist / Japanese film scrutinizes pop culture". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- Henderson, Tim (August 12, 2010). "Perfect Blue Review". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- Lumbard, Neil (October 23, 2020). "Blu-ray.com Reviewer: Perfect Blue". Blu-Ray.com. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- Beveridge, Chris (January 15, 2021). "Perfect Blue Blu-ray Anime Review". The Fandom Post. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- Clements & McCarthy 2012 – entry: Urotsukidoji

- Cinquemani, Sal (September 10, 2001). "Madonna: Drowned World Tour Review". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on March 20, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

Though her Cowgirl image is easily her least significant incarnation to date, Drowned World proves that Madonna is still unmatched in her ability to lift cultural iconography into the mainstream. The Geisha cycle is epilogued with hard techno beats and violent imagery taken from the groundbreaking Japanese anime film, Perfect Blue. The story's main character, Mima, a former pop star haunted by ghosts from her past, dreams of becoming an actress but resorts to porn gigs in her search for success.

- Denney, Alex (August 27, 2015). "The cult Japanese filmmaker that inspired Darren Aronofsky". Dazed. Archived from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- "KON'S TONE » VSダーレン". Konstone.s-kon.net. January 23, 2001. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- 2011/06/22 水曜日 - 高橋かしこ (June 22, 2011). "コンズ便り »コンズ便り» ブログアーカイブ » 雑食日誌2000 - KON'S TONE". Konstone.s-kon.net. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- "VS Dahlen". January 23, 2001. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- Ressler, Karen (April 10, 2017). "Seven Seas Licenses Yoshikazu Takeuchi's Original Perfect Blue Novels". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on September 8, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- Book references

- Clements, Jonathan; McCarthy, Helen (2012). The Anime Encyclopedia, Revised & Expanded Edition: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917. Stone Bridge Press. 867pp. ISBN 9781611725155.

External links

- Official Manga Entertainment website at the Wayback Machine (archived March 9, 2012)

- Official Geneon Entertainment website (in Japanese)

- Official Madhouse Animation website (in Japanese)

- Official Rex Entertainment website at the Wayback Machine (archived February 25, 1999) (in Japanese)

- Perfect Blue (anime) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- Perfect Blue at IMDb

- Perfect Blue at Rotten Tomatoes

- Perfect Blue at Box Office Mojo