Perfect graph

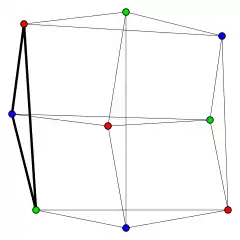

In graph theory, a perfect graph is a graph in which the chromatic number of every induced subgraph equals the order of the largest clique of that subgraph (clique number). Equivalently stated in symbolic terms an arbitrary graph is perfect if and only if for all we have .

The perfect graphs include many important families of graphs and serve to unify results relating colorings and cliques in those families. For instance, in all perfect graphs, the graph coloring problem, maximum clique problem, and maximum independent set problem can all be solved in polynomial time. In addition, several important min-max theorems in combinatorics, such as Dilworth's theorem, can be expressed in terms of the perfection of certain associated graphs.

Properties

- By the perfect graph theorem, a graph is perfect if and only if its complement is perfect.

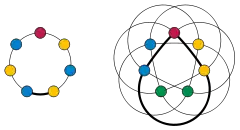

- By the strong perfect graph theorem, perfect graphs are the same as Berge graphs, which are graphs where neither nor contains an induced cycle of odd length 5 or more.

See below section for more details.

History

The theory of perfect graphs developed from a 1958 result of Tibor Gallai that in modern language can be interpreted as stating that the complement of a bipartite graph is perfect; this result can also be viewed as a simple equivalent of Kőnig's theorem, a much earlier result relating matchings and vertex covers in bipartite graphs. The first use of the phrase "perfect graph" appears to be in a 1963 paper of Claude Berge, after whom Berge graphs are named. In this paper he unified Gallai's result with several similar results by defining perfect graphs, and he conjectured the equivalence of the perfect graph and Berge graph definitions; his conjecture was proved in 2002 as the strong perfect graph theorem.

Families of graphs that are perfect

Some of the more well-known perfect graphs are:[1]

- Bipartite graphs, which are graphs that can be colored with two colors, including forests (graphs without cycles).

- Line graphs of bipartite graphs (see Kőnig's theorem). Rook's graphs (line graphs of complete bipartite graphs) are a special case.

- Chordal graphs, the graphs in which every cycle of four or more vertices has a chord, an edge between two vertices that are not consecutive in the cycle. These include

- forests, k-trees (maximal graphs with a given treewidth),

- split graphs (graphs that can be partitioned into a clique and an independent set),

- block graphs (graphs in which every biconnected component is a clique),

- Ptolemaic graphs (graphs whose distances obey Ptolemy's inequality),

- interval graphs (graphs in which each vertex represents an interval of a line and each edge represents a nonempty intersection between two intervals),

- trivially perfect graphs (interval graphs for nested intervals), threshold graphs (graphs in which two vertices are adjacent when their total weight exceeds a numerical threshold),

- windmill graphs (formed by joining equal cliques at a common vertex),

- and strongly chordal graphs (chordal graphs in which every even cycle of length six or more has an odd chord).

- Comparability graphs formed from partially ordered sets by connecting pairs of elements by an edge whenever they are related in the partial order. These include:

- bipartite graphs, complements of interval graphs, trivially perfect graphs, threshold graphs, windmill graphs,

- permutation graphs (graphs in which the edges represent pairs of elements that are reversed by a permutation),

- and cographs (graphs formed by recursive operations of disjoint union and complementation).

- Perfectly orderable graphs, which are graphs that can be ordered in such a way that a greedy coloring algorithm is optimal on every induced subgraph. These include the bipartite graphs, the chordal graphs, the comparability graphs,

- distance-hereditary graphs (in which shortest path distances in connected induced subgraphs equal those in the whole graph),

- and wheel graphs with an odd number of vertices.

- Trapezoid graphs, which are intersection graphs of trapezoids whose parallel pairs of edges lie on two parallel lines. These include the interval graphs, trivially perfect graphs, threshold graphs, windmill graphs, and permutation graphs; their complements are a subset of the comparability graphs.

Relation to min-max theorems

In all graphs, the clique number provides a lower bound for the chromatic number, as all vertices in a clique must be assigned distinct colors in any proper coloring. The perfect graphs are those for which this lower bound is tight, not just in the graph itself but in all of its induced subgraphs. For graphs that are not perfect, the chromatic number and clique number can differ; for instance, a cycle of length five requires three colors in any proper coloring but its largest clique has size two.

A proof that a class of graphs is perfect can be seen as a min-max theorem: the minimum number of colors needed for these graphs equals the maximum size of a clique. Many important min-max theorems in combinatorics can be expressed in these terms. For instance, Dilworth's theorem states that the minimum number of chains in a partition of a partially ordered set into chains equals the maximum size of an antichain, and can be rephrased as stating that the complements of comparability graphs are perfect. Mirsky's theorem states that the minimum number of antichains into a partition into antichains equals the maximum size of a chain, and corresponds in the same way to the perfection of comparability graphs.

The perfection of permutation graphs is equivalent to the statement that, in every sequence of ordered elements, the length of the longest decreasing subsequence equals the minimum number of sequences in a partition into increasing subsequences. The Erdős–Szekeres theorem is an easy consequence of this statement.

Kőnig's theorem in graph theory states that a minimum vertex cover in a bipartite graph corresponds to a maximum matching, and vice versa; it can be interpreted as the perfection of the complements of bipartite graphs. Another theorem about bipartite graphs, that their chromatic index equals their maximum degree, is equivalent to the perfection of the line graphs of bipartite graphs.

Characterizations and the perfect graph theorems

In his initial work on perfect graphs, Berge made two important conjectures on their structure that were only proved later.

The first of these two theorems was the perfect graph theorem of Lovász (1972), stating that a graph is perfect if and only if its complement is perfect. Thus, perfection (defined as the equality of maximum clique size and chromatic number in every induced subgraph) is equivalent to the equality of maximum independent set size and clique cover number.

The second theorem, conjectured by Berge, provided a forbidden graph characterization of perfect graphs. An induced cycle of odd length at least 5 is called an odd hole. An induced subgraph that is the complement of an odd hole is called an odd antihole. An odd cycle of length greater than 3 cannot be perfect, because its chromatic number is three and its clique number is two. Similarly, the complement of an odd cycle of length 2k + 1 cannot be perfect, because its chromatic number is k + 1 and its clique number is k. (Alternatively, the imperfection of this graph follows from the perfect graph theorem and the imperfection of the complementary odd cycle). Because these graphs are not perfect, every perfect graph must be a Berge graph, a graph with no odd holes and no odd antiholes. Berge conjectured the converse, that every Berge graph is perfect. This was finally proven as the strong perfect graph theorem of Chudnovsky, Robertson, Seymour, and Thomas (2006). It trivially implies the perfect graph theorem, hence the name.

The perfect graph theorem has a short proof, but the proof of the strong perfect graph theorem is long and technical, based on a deep structural decomposition of Berge graphs. Related decomposition techniques have also borne fruit in the study of other graph classes, and in particular for the claw-free graphs.

There is a third theorem, again due to Lovász, which was originally suggested by Hajnal. It states that a graph is perfect if the sizes of the largest clique, and the largest independent set, when multiplied together, equal or exceed the number of vertices of the graph, and the same is true for any induced subgraph. It is an easy consequence of the strong perfect graph theorem, while the perfect graph theorem is an easy consequence of it.

The Hajnal characterization is not met by odd n-cycles or their complements for n > 3: the odd cycle on n > 3 vertices has clique number 2 and independence number (n − 1)/2. The reverse is true for the complement, so in both cases the product is n − 1.

Algorithms on perfect graphs

In all perfect graphs, the graph coloring problem, maximum clique problem, and maximum independent set problem can all be solved in polynomial time (Grötschel, Lovász & Schrijver 1988). The algorithm for the general case involves the Lovász number of these graphs, which (for the complement of a given graph) is sandwiched between the chromatic number and clique number. Calculating the Lovász number can be formulated as a semidefinite program and approximated numerically in polynomial time using the ellipsoid method for linear programming. For perfect graphs, rounding this approximation to an integer gives the chromatic number and clique number in polynomial time; the maximum independent set can be found by applying the same approach to the complement of the graph. However, this method is complicated and has a high polynomial exponent. More efficient combinatorial algorithms are known for many special cases.

For many years the complexity of recognizing Berge graphs and perfect graphs remained open. From the definition of Berge graphs, it follows immediately that their recognition is in co-NP (Lovász 1983). Finally, subsequent to the proof of the strong perfect graph theorem, a polynomial time algorithm was discovered by Chudnovsky, Cornuéjols, Liu, Seymour, and Vušković.

References

- Berge, Claude (1961). "Färbung von Graphen, deren sämtliche bzw. deren ungerade Kreise starr sind". Wiss. Z. Martin-Luther-Univ. Halle-Wittenberg Math.-Natur. Reihe. 10: 114.

- Berge, Claude (1963). "Perfect graphs". Six Papers on Graph Theory. Calcutta: Indian Statistical Institute. pp. 1–21.

- Chudnovsky, Maria; Cornuéjols, Gérard; Liu, Xinming; Seymour, Paul; Vušković, Kristina (2005). "Recognizing Berge graphs". Combinatorica. 25 (2): 143–186. doi:10.1007/s00493-005-0012-8.

- Chudnovsky, Maria; Robertson, Neil; Seymour, Paul; Thomas, Robin (2006). "The strong perfect graph theorem". Annals of Mathematics. 164 (1): 51–229. arXiv:math/0212070. doi:10.4007/annals.2006.164.51.

- Gallai, Tibor (1958). "Maximum-minimum Sätze über Graphen". Acta Math. Acad. Sci. Hung. 9 (3–4): 395–434. doi:10.1007/BF02020271.

- Golumbic, Martin Charles (1980). Algorithmic Graph Theory and Perfect Graphs. Academic Press. ISBN 0-444-51530-5. Archived from the original on 2010-05-22. Retrieved 2007-11-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Second edition, Annals of Discrete Mathematics 57, Elsevier, 2004.

- Grötschel, Martin; Lovász, László; Schrijver, Alexander (1988). Geometric Algorithms and Combinatorial Optimization. Springer-Verlag. See especially chapter 9, "Stable Sets in Graphs", pp. 273–303.

- Lovász, László (1972). "Normal hypergraphs and the perfect graph conjecture". Discrete Mathematics. 2 (3): 253–267. doi:10.1016/0012-365X(72)90006-4.

- Lovász, László (1972). "A characterization of perfect graphs". Journal of Combinatorial Theory. Series B. 13 (2): 95–98. doi:10.1016/0095-8956(72)90045-7.

- Lovász, László (1983). "Perfect graphs". In Beineke, Lowell W.; Wilson, Robin J. (eds.). Selected Topics in Graph Theory, Vol. 2. Academic Press. pp. 55–87. ISBN 0-12-086202-6.

External links

- The Strong Perfect Graph Theorem by Václav Chvátal.

- Open problems on perfect graphs, maintained by the American Institute of Mathematics.

- Perfect Problems, maintained by Václav Chvátal.

- Information System on Graph Class Inclusions: perfect graph