Periphrasis

In linguistics, periphrasis (/pəˈrɪfrəsɪs/)[1] is the usage of multiple separate words to carry the meaning of prefixes, suffixes or verbs, among other things, where either would be possible. Technically, it is a device where grammatical meaning is expressed by one or more free morphemes (typically one or more function words accompanying a content word), instead of by inflectional affixes or derivation.[2] Periphrastic forms are an example of analytic language, whereas the absence of periphrasis is a characteristic of synthetic language. While periphrasis concerns all categories of syntax, it is most visible with verb catenae. The verb catenae of English are highly periphrastic.

Examples

The distinction between inflected and periphrastic forms is usually illustrated across distinct languages. However, comparative and superlative forms of adjectives (and adverbs) in English provide a straightforward illustration of the phenomenon.[3] For many speakers, both the simple and periphrastic forms in the following table are possible:

| Inflected form of the comparative (-er) | Periphrastic equivalent |

|---|---|

| loveli-er | more lovely |

| friendli-er | more friendly |

| happi-er | more happy |

| Inflected form of the superlative (-est) | Periphrastic equivalent |

| loveli-est | most lovely |

| friendli-est | most friendly |

| happi-est | most happy |

The periphrastic forms are periphrastic by virtue of the appearance of more or most, and they therefore contain two words instead of just one. The words more and most contribute functional meaning only, just like the inflectional affixes -er and -est. The distinction is also evident across full verbs and the corresponding light verb constructions:

| Full verb | Periphrastic light verb alternative |

|---|---|

| (to) present | (to) give a presentation |

| (to) shower | (to) take/have a shower |

| (to) converse | (to) have a conversation |

| (to) smoke | (to) have a smoke |

The light verb constructions are periphrastic because the light verbs (give, take, have) have little semantic content. They contribute mainly functional meaning. The main semantic content of these light verb constructions lies with the noun phrase.

Across languages

English vs Latin

Such distinctions occur in many languages. The following table provides some examples across Latin and English:

| Latin (inflected) | English (periphrastic) |

|---|---|

| stēll-ae | of a star |

| patient-issimus | most patient |

| amā-be-ris | (you) will be loved |

Periphrasis is a characteristic of analytic languages, which tend to avoid inflection. Even strongly inflected synthetic languages sometimes make use of periphrasis to fill out an inflectional paradigm that is missing certain forms.[4] A comparison of some Latin forms of the verb dūcere 'lead' with their English translations illustrates further that English uses periphrasis in many instances where Latin uses inflection.

| Latin | English equivalent | grammatical classification |

|---|---|---|

| dūc-ē-bāmur | (we) were led | 1st person plural imperfect passive indicative |

| dūc-i-mur | (we) are led | 1st person plural present passive indicative |

| dūc-ē-mur | (we) will be led | 1st person plural future passive indicative |

English often needs two or three verbs to express the same meaning that Latin expresses with a single verb. Latin is a relatively synthetic language; it expresses grammatical meaning using inflection, whereas the verb system of English, a Germanic language, is relatively analytic; it uses auxiliary verbs to express functional meaning.

Israeli Hebrew

Unlike Classical Hebrew, Israeli Hebrew uses a few periphrastic verbal constructions in specific circumstances, such as slang or military language. Consider the following pairs/triplets, in which the first is/are an Israeli Hebrew analytic periphrasis and the last is a Classical Hebrew synthetic form:[5]

(1) שם צעקה ‘’sam tseaká’’ “shouted” (which literally means “put a shout”) vis-à-vis צעק ‘’tsaák’’ “shouted”

(2) נתן מבט ‘’natán mabát’’ “looked” (which literally means “gave a look”) AND העיף מבט ‘’heíf mabát’’ “looked” (literally “flew/threw a look”; cf. the English expressions ‘’cast a glance’’, ‘’threw a look’’ and ‘’tossed a glance’’) vis-à-vis the Hebrew-descent הביט ‘’hibít’’ “looked at”.

According to Ghil'ad Zuckermann, the Israeli periphrastic construction (using auxiliary verbs followed by a noun) is employed here for the desire to express swift action, and stems from Yiddish. He compares the Israeli periphrasis to the following Yiddish expressions all meaning “to have a look”:

(1) געבן א קוק ‘’gébņ a kuk’’, which literally means “to give a look”

(2) טאן א קוק ‘’ton a kuk’’, which literally means “to do a look”

(3) the colloquial expression כאפן א קוק ‘’khapņ a kuk’’, which literally means “to catch a look”.

Zuckermann emphasizes that the Israeli periphrastic constructions “are not nonce, ad hoc lexical calques of Yiddish. The Israeli system is productive and the lexical realization often differs from that of Yiddish”. He provides the following Israeli examples:

הרביץ hirbíts “hit, beat; gave”, yielded

הרביץ מהירות ‘’hirbíts mehirút’’ “drove very fast” (מהירות ‘’mehirút’’ meaning “speed”), and

הרביץ ארוחה ‘’hirbíts arukhá’’ “ate a big meal” (ארוחה ‘’arukhá’’ meaning “meal”), cf. English ‘’hit the buffet’’ “eat a lot at the buffet”; ‘’hit the liquor/bottle’’ “drink alcohol”.

The Israeli Hebrew periphrasis דפק הופעה ‘’dafák hofaá’’, which literally means “hit an appearance”, actually means “dressed smartly”.[6]

But while Zuckermann attempted to use these examples to claim that Israeli Hebrew grew similar to European languages, it will be noticed that all of these examples are from the slang and therefore linguistically marked. The normal and daily usage of the verb paradigm in Israeli modern Hebrew is of the synthetic form: צָעַק, הִבִּיט

Catenae

The correspondence in meaning across inflected forms and their periphrastic equivalents within the same language or across different languages leads to a basic question. Individual words are always constituents, but their periphrastic equivalents are often NOT constituents. Given this mismatch in syntactic form, one can pose the following questions: how should the form-meaning correspondence across periphrastic and non-periphrastic forms be understood?; how does it come to pass that a specific meaning bearing unit can be a constituent in one case but in another case, it is a combination of words that does not qualify as a constituent? An answer to this question that has recently come to light is expressed in terms of the catena unit, as implied above.[7] The periphrastic word combinations are catenae even when they are not constituents, and individual words are also catenae. The form-meaning correspondence is therefore consistent. A given inflected one-word catena corresponds to a periphrastic multiple-word catena.

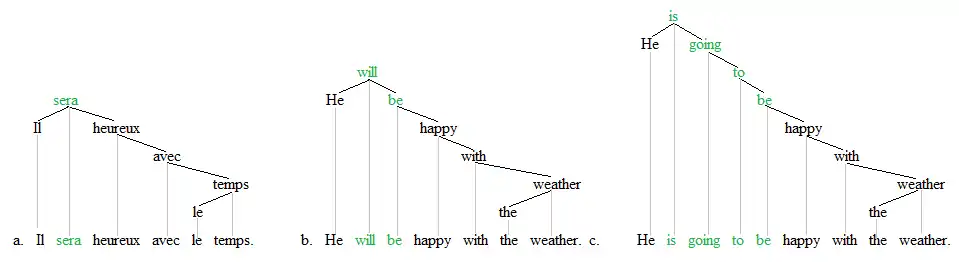

The role of catenae for the theory of periphrasis is illustrated with the trees that follow. The first example is across French and English. Future tense/time in French is often constructed with an inflected form, whereas English typically employs a periphrastic form, e.g.

Where French expresses future tense/time using the single (inflected) verb catena sera, English employs a periphrastic two-word catena, or perhaps a periphrastic four-word catena, to express the same basic meaning. The next example is across German and English:

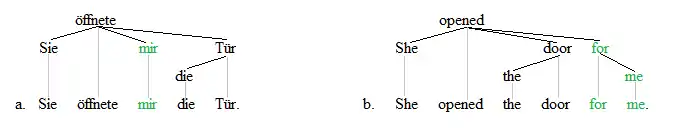

German often expresses a benefiter with a single dative case pronoun. For English to express the same meaning, it usually employs the periphrastic two-word prepositional phrase with for. The following trees illustrate the periphrasis of light verb constructions:

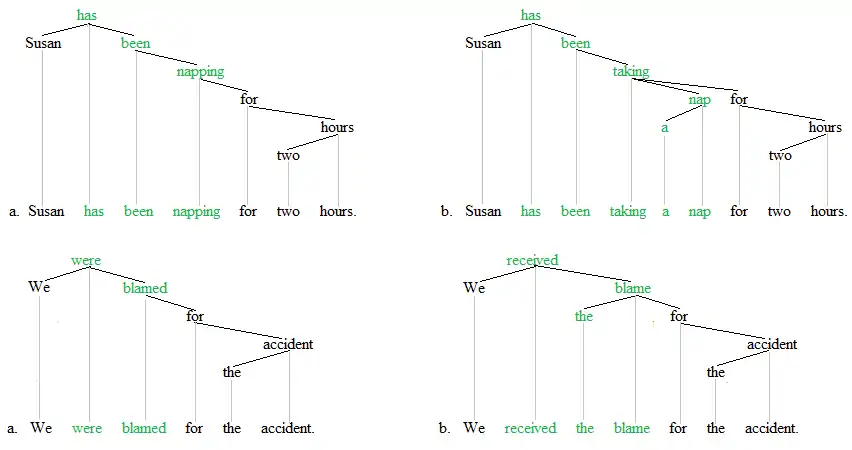

Each time, the catena in green is the matrix predicate. Each of these predicates is a periphrastic form insofar at least one function word is present. The b-predicates are, however, more periphrastic than the a-predicates since they contain more words. The closely similar meaning of these predicates across the a- and b-variants is accommodated in terms of catenae, since each predicate is a catena.

Notes

- "periphrasis | Definition of periphrasis in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 2018-02-01.

- Concerning periphrasis in general, see Matthews (1991:11f., 236-238).

- Concerning the competing forms of the comparative and superlative in English as an illustration of periphrasis, see Matthews (1981:55).

- Concerning the use of periphrasis in strongly inflected languages, see Stump (1998).

- See p. 51 in Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2009), "Hybridity versus Revivability: Multiple Causation, Forms and Patterns", Journal of Language Contact, Varia 2, pp. 40-67.

- See p. 51 in Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2009), "Hybridity versus Revivability: Multiple Causation, Forms and Patterns", Journal of Language Contact, Varia 2, pp. 40-67.

- Concerning catenae, see Osborne and Groß (2012a) and Osborne et al (2012b).

References

- Matthews, P. 1981. Syntax. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Matthews, P. 1991. Morphology, 2nd edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Osborne, T. and T. Groß 2012a. Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets Dependency Grammar. Cognitive Linguistics 23, 1, 163-214.

- Osborne, T., M. Putnam, and T. Groß 2012b. Catenae: Introducing a novel unit of syntactic analysis. Syntax 15, 4, 354-396.

- Stump, G. 1998. Inflection. In A. Spencer and A. M. Zwicky (eds.), The handbook of morphology. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 13–43.

External References

https://www.smg.surrey.ac.uk/periphrasis/ Surrey periphrasis database