Perseids

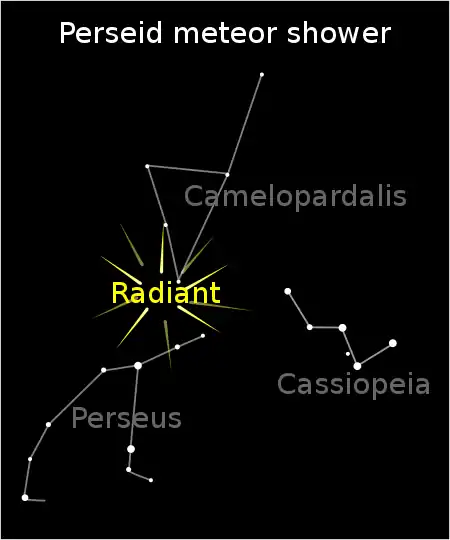

The Perseids are a prolific meteor shower associated with the comet Swift–Tuttle. The meteors are called the Perseids because the point from which they appear to hail (called the radiant) lies in the constellation Perseus.

| Perseids (PER) | |

|---|---|

Perseids in 2017 as seen from the White Desert, Egypt | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈpɜːrsiɪdz/ |

| Discovery date | AD 36 (first record)[1][2] |

| Parent body | Comet Swift–Tuttle[3] |

| Radiant | |

| Constellation | Perseus |

| Right ascension | 03h 04m [3] |

| Declination | +58°[3] |

| Properties | |

| Occurs during | July 17 – August 24 |

| Date of peak | August 12 |

| Velocity | 58[4] km/s |

| Zenithal hourly rate | 120[3] |

Etymology

The name is derived from the word Perseidai (Greek : Περσείδαι), the sons of Perseus in Greek mythology.

Characteristics

The stream of debris is called the Perseid cloud and stretches along the orbit of the comet Swift–Tuttle. The cloud consists of particles ejected by the comet as it travels on its 133-year orbit.[5] Most of the particles have been part of the cloud for around a thousand years. However, there is also a relatively young filament of dust in the stream that was pulled off the comet in 1865, which can give an early mini-peak the day before the maximum shower.[6] The dimensions of the cloud in the vicinity of the Earth are estimated to be approximately 0.1 astronomical units (AU) across and 0.8 AU along the Earth's orbit, spread out by annual interactions with the Earth's gravity.[7]

The shower is visible from mid-July each year, with the peak in activity between 9 and 14 August, depending on the particular location of the stream. During the peak, the rate of meteors reaches 60 or more per hour. They can be seen all across the sky; however, because of the shower's radiant in the constellation of Perseus, the Perseids are primarily visible in the Northern Hemisphere.[8] As with many meteor showers the visible rate is greatest in the pre-dawn hours, since more meteoroids are scooped up by the side of the Earth moving forward into the stream, corresponding to local times between midnight and noon, as can be seen in the accompanying diagram.[9] While many meteors arrive between dawn and noon, they are usually not visible due to daylight. Some can also be seen before midnight, often grazing the Earth's atmosphere to produce long bright trails and sometimes fireballs. Most Perseids burn up in the atmosphere while at heights above 80 kilometres (50 mi).[10]

Gallery

The radiant point for the Perseid meteor shower

The radiant point for the Perseid meteor shower A meteoroid of the Perseids with a size of about ten millimetres entering the Earth's atmosphere in slow motion (x 0.1). The meteoroid is at the bright head of the trail, and the recombination glow of the ionised mesosphere is still visible for about 0.7 seconds in the tail.

A meteoroid of the Perseids with a size of about ten millimetres entering the Earth's atmosphere in slow motion (x 0.1). The meteoroid is at the bright head of the trail, and the recombination glow of the ionised mesosphere is still visible for about 0.7 seconds in the tail.

(Variant of the animation in real time) A near-Earth perspective of its orbit, the radiant of the Perseid meteor shower, and the orbit of the shower's parent comet, 109P/Swift-Tuttle, to show their spatial relationships on August 12 00:00 UTC. The Perseid debris cloud is fairly wide (~0.1 AU), filling the frame.

A near-Earth perspective of its orbit, the radiant of the Perseid meteor shower, and the orbit of the shower's parent comet, 109P/Swift-Tuttle, to show their spatial relationships on August 12 00:00 UTC. The Perseid debris cloud is fairly wide (~0.1 AU), filling the frame.

Peak times

| Year | Perseids active between | Peak of shower |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | July 16 – August 23[11] | August 12–13 (ZHRmax 100) (full moon on Aug 3)[11] |

| 2019 | July 17 – August 24 | August 12–13[12] (ZHRmax 80) (full moon on Aug 15) |

| 2018 | July 17 – August 24 | August 11–13[13] (ZHRmax 60) |

| 2017 | July 17 – August 24 | August 12[14] |

| 2016 | July 17 – August 24 | August 11–12 [15] (ZHRmax 150) |

| 2015 | July 17 – August 24 | August 12–13[16] (ZHRmax 95) (new moon on Aug 14) |

| 2014 | July 17 – August 24 | August 13 (ZHRmax 68)[17] (full moon on Aug 10) |

| 2013 | July 17 – August 24 | August 12 (ZHRmax 109)[18] |

| 2012 | July 17 – August 24 | August 12 (ZHRmax 122)[19] |

| 2011 | July 17 – August 24 | August 12 (ZHRmax 58)[20] (full moon on Aug 13)[21] |

| 2010 | July 23 – August 24 | August 12 (ZHRmax 142)[22] |

| 2009 | July 14 – August 24 | August 13 (ZHRmax 173) (The estimated peak was 173,[23] but a gibbous Moon washed out fainter meteors.) |

| 2008 | July 25 – August 24[24] | August 13 (ZHRmax 116)[24] |

| 2007 | July 19 – August 25[25] | August 13 (ZHRmax 93)[25] |

| 2006 | August 12/13 (ZHRmax 100)[26] | |

| 2005 | August 12 (ZHR max 90[27])[28] | |

| 2004 | August 12 (ZHRmax >200)[4] | |

| 1994 | (ZHRmax >200)[2] | |

| 1993 | (ZHRmax 200–500)[2] | |

| 1992 | August 11 (outburst under a full moon on Aug 13)[29] | |

| 1883 | August 9 or earlier[30] | August 11 (ZHRmax 43)[30] |

| 1864 | (ZHRmax >100)[2] | |

| 1863 | (ZHRmax 109–215)[2] | |

| 1861 | (ZHRmax 78–102)[2] | |

| 1858 | (ZHRmax 37–88)[2] | |

| 1839 | (ZHRmax 165)[2] |

Historical observations and associations

Some Catholics refer to the Perseids as the "tears of Saint Lawrence", suspended in the sky but returning to Earth once a year on August 10, the canonical date of that saint's martyrdom in 258 AD.[31] The saint is said to have been burned alive on a gridiron, and this tradition is almost certainly the origin of the Mediterranean folk legend that the shooting stars are the sparks of that fire and that during the night of August 9–10 its cooled embers appear in the ground under plants, and which are known as the "coal of Saint Lawrence".[32][33] The transition in favor of the Catholic saint and his feast day on August 10 and away from pagan gods and their festivals, known as Christianization, was facilitated by the phonetic assonance of the Latin name Laurentius with Larentia.[34][35]

In 1835, Adolphe Quetelet identified the shower as emanating from the constellation Perseus.[1][2] In 1866, after the perihelion passage of Swift-Tuttle in 1862, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli discovered the link between meteor showers and comets. The finding is contained in an exchange of letters with Angelo Secchi.

In popular culture

In his 1972 song "Rocky Mountain High", American singer-songwriter John Denver refers to his experience watching the Perseid meteor shower during a family camping trip in the mountains near Aspen, Colorado, with the chorus lyric, "I've seen it raining fire in the sky."

In his 2006 novel Against the Day, American novelist Thomas Pynchon refers to the Perseid meteor showers being watched by three characters west of the Dolores Valley after playing a game of tarot.

In the popular Japanese band Sandaime J Soul Brothers's 2013 song "R.Y.U.S.E.I" (Meteor), they describe the Perseid meteor as falling like an evening rain shower – its shooting stars like raindrops pulling their tails behind them.

In the 2014 song “RPG,” by Japanese band Sekai no Owari, the narrator mentions watching the Perseid meteor shower on the night something “precious to them fell apart.”

The 2014 pop song "Meteorites" by Canadian musician LIGHTS uses Perseids as a metaphor for escaping financial hardship.

See also

- Leonids, associated with the comet Tempel–Tuttle

References

- Dr. Bill Cooke; Danielle Moser & Rhiannon Blaauw (2012-08-11). "NASA Chat: Stay 'Up All Night' to Watch the Perseids!" (PDF). NASA. p. 55. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- Gary W. Kronk. "Observing the Perseids". Meteor Showers Online. Archived from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- Moore, Patrick; Rees, Robin (2011), Patrick Moore's Data Book of Astronomy (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 275, ISBN 978-0521899352

- Żołądek, P.; et al. (October 2009), "The 2004 Perseid meteor shower – Polish Fireball Network double station preliminary results", Journal of the International Meteor Organization, 37 (5): 161–163, Bibcode:2009JIMO...37..161Z

- Dan Vergano (2010-08-07). "Perseid meteor shower to light up night sky this weekend". Usatoday.com. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- Dr. Tony Phillips (June 25, 2004). "The 2004 Perseid Meteor Shower". Science@NASA. Archived from the original on March 20, 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- D.W. Hughes (1996). "Cometary Dust Loss: Meteoroid Streams and the Inner Solar System Dust Cloud". In J. Mayo Greenberg (ed.). The Cosmic Dust Connection. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 375. ISBN 9789401156523.

- "Perseids Meteor Shower 2018". timeanddate.com. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-08-17. Retrieved 2015-07-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "NASA All Sky Fireball Network: Perseid End Height". NASA Meteor Watch on Facebook. 2012-08-11. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- "Perseid meteor shower 2020: When and where to see it in the UK". Royal Museums Greenwich. 2020-07-23. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- "Perseid meteor shower 2019: When and where to see it in the UK". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- Sarah Lewin (July 9, 2018). "Perseid Meteor Shower 2018: When, Where & How to See It". Space.com. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- Sarah Lewin (July 26, 2017). "Perseid Meteor Shower 2017: When, Where & How to See It". Space.com. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- "Perseid Meteor Shower 2016: When, Where & How to See It". Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- "Meteor Showers 2015". NASA. Retrieved 2015-08-09.

- "Perseids 2014: visual data quicklook". Imo.net. 2014-08-13. Archived from the original on 2016-10-24. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- "Perseids 2013: visual data quicklook". Imo.net. 2013-09-23. Archived from the original on 2016-10-24. Retrieved 2014-04-20.

- "Perseids 2012: visual data quicklook". Imo.net. 2012-10-22. Archived from the original on 2014-04-21. Retrieved 2014-04-20.

- "Perseids 2011: visual data quicklook". Imo.net. 2011-10-06. Archived from the original on 2013-11-06. Retrieved 2014-04-20.

- "How to See the Best Meteor Showers of the Year: Tools, Tips and 'Save the Dates'". nasa.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-16.

- "How to See the Best Meteor Showers of the Year: Tools, Tips and 'Save the Dates'". nasa.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- "Perseids 2009: visual data quicklook". Imo.net. 2010-04-26. Archived from the original on 2016-10-16. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- "Perseids 2008: visual data quicklook". Imo.net. 2009-06-06. Archived from the original on 2016-10-24. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- Perseids 2007: first results Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- EAAS

- http://www.imo.net/perseids-2005-visual/

- https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2005/22jul_perseids2005

- Brown (1992). "The Perseids 1992. New outburst announces return of P/Swift-Tuttle". WGN. 20 (5): 192. Bibcode:1992JIMO...20..192B.

- Corder, H (22 October 1883). "1883Obs.....6..338C Page 338". Adsabs.harvard.edu. Bibcode:1883Obs.....6..338C. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- "Science: Tears of St. Lawrence". TIME. 1926-08-23. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- (in Italian) Falling stars and coal under the basil

- (in Italian) The Coal of Saint Lawrence

- (in Italian) Castrum Inui

- "SHOOTING STARS". utestudents BLOG.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Perseids. |

- Where to see the Perseids and public stargazing events in the UK (Go Stargazing)

- Worldwide viewing times for the 2016 Perseids meteor shower

- All you need to know about the Perseid meteor shower (Paul Sutherland)

- How to photograph the Perseid meteor shower (Skymania)

- Perseid Observing Conditions (The International Project for Radio Meteor Observation)

- 2014 Perseids Radio results (RMOB)

- Perseid Visibility Map (2014 NASA Meteoroid Environment Office)

- 2009 Perseid Meteor Fireball

- NASA website on the Perseid shower of 2009

- Sky & Telescope Magazine – Perseids at Their Prime

- 2012 Image of Perseids emanating from the radiant

- What are the perseids?