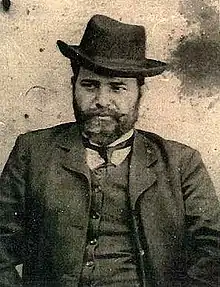

Petar Poparsov

Petar Pop-Arsov[1] (Bulgarian: Петър Попарсов, Macedonian: Петар Поп Арсов) originally spelled in older Bulgarian orthography: Петъръ попъ Арсовъ; (August 14, 1868 in Bogomila, Ottoman Empire, (present day North Macedonia) – January 1, 1941 in Sofia, Bulgaria) was a Bulgarian educator and revolutionary from Macedonia,[2][3][4] one of the founders of the Internal Macedonian Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO), known in its early times as Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (BMARC).[5] Although he was Bulgarian teacher[6][7] and revolutionary,[8] and thought of his compatriots as Bulgarians,[9][10] according to the post-WWII Macedonian historiography,[11][12] he was an ethnic Macedonian.[13][14]

Petar Pop-Arsov | |

|---|---|

revolutionary | |

| Born | August 14, 1868 |

| Died | January 1, 1941 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | Ottoman/Bulgarian |

Early life

He was born in 1868 in the village Bogomila, near Veles. He was one of the leaders of the student protest in the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki in 1887/1888 where the main objective was to replace the East Bulgarian dialect with a Macedonian dialect in the lecturing. As a consequence, he was expelled along with 38 other students. He managed to enroll in the philology studies program at Belgrade University in 1888, but because his resistance to Serbianisation, he was once more evicted in 1890.[15] In 1892 he graduated in Slavistics from Sofia University.

Young Macedonian Literary Society

In 1891 he is one of the founders of Young Macedonian Literary Society in Sofia and its magazine Loza (The Vine). The purpose of the society was twofold: the official one was primarily scholarly and literary. One of the purposes of the magazine of Young Macedonian Literary Society was to defend the idea the dialects from Macedonia to be more represented in Bulgarian literature language. The articles where historical, cultural and ethnographic. The authors of this magazine clearly considered them as Macedonian Bulgarians, but the Bulgarian government suspected them of the lack of loyalty and some separatism and the magazine was promptly banned by the Bulgarian authorities after several issues.

IMARO

The best proof of the aims and tasks of the Young Macedonian Literary Society was provided during the following year when its members became either founders of or active participants in "The Committee for Obtaining the Political Rights Given to Macedonia by the Congress of Berlin" from which, as Petar Poparsov says, there later developed IMARO. These were the Macedonian intellectuals who were "the witnesses to the hellish condition of Macedonia and took account of the geographical, ethnographic, economic and other characteristics of the country". In 1894 Petŭr Poparsov was asked by the founders to prepare a draft for the first statute of the IMARO, based on the Statute of Vasil Levski's Internal Revolutionary Organization, which was available to them in Zahari Stoyanov's Notes on the Bulgarian Uprisings.[18] Some Macedonian and Bulgarian researchers assume, that in this first statute the organization was called Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees, and Poparsov was its author.[19][20][21]

From 1896-7 he worked in Štip as a Bulgarian teacher and president of the regional IMARO section. In 1897 he was arrested by Ottoman authorities on charges of inciting rebellion, and sentenced to 101 years in prison. He was pardoned in August 1902. After his release he encountered a changed political climate in Macedonia. He remained passive during the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising of 1903. However, after the failure of the uprising, he was admitted to the Central Committee of IMARO. At the Rila Congress in November 1905, he was elected in the representative body of IMARO. He championed the idea of Macedonian autonomy. After the Young Turk revolution of 1908, he took an active part in the preparation and holding of the elections for the Ottoman Parliament with the list of the People's Federative Party (Bulgarian Section) but did not receive the necessary number of votes for a deputy.

During the First Balkan War he participated in an unsuccessful meeting attended by some local revolutionaries from the left wing of the IMARO in Veles. It was organized by Dimitrija Čupovski and its aim was to authorize representatives to participate in the London peace conference. They had to try to preserve the integrity of the region of Macedonia.[22]

In Bulgaria

After the Balkan Wars he moved to Bulgaria. Here he married to Hrisanta Nasteva, a former teacher of Bulgarian girls school at Thessaloniki. They settled in Kostenets in 1914, where he continuous taught from 1914 to 1929. He worked not only as a teacher but also a director to his retirement. His brother Andrey Poparsov was Mayor of Bogomila during the Bulgarian rule in the area in the First World War, but was killed in October 1918 by the Serbian authorities. In 1920, he protested against the Serbianization of Macedonian Bulgarians implemented in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and described its early stages in Macedonia as one of the most powerful factors to the creation of the IMRO.[23]

He died after a brief illness in Sofia in 1941.

Books

- Стамболовщината въ Македония и нейнитѣ прѣдставители - Петъръ Попъ Арсовъ

Notes

- His last name is sometimes rendered 'Poparsov' or 'Pop Arsov'.

- We, the people: politics of national peculiarity in Southeastern Europe, Автор Diana Mishkova, Издател Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 963-9776-28-9, стр. 116.

- The Macedonian question: Britain and the southern Balkans : 1939-1949, Автор Dimitris Livanios, Издател Oxford University Press US, 2008, ISBN 0-19-923768-9, стр. 18.

- Preparation for a revolution: the Young Turks, 1902-1908, Автор M. Şükrü Hanioğlu, Издател Oxford University Press US, 2001, ISBN 0-19-513463-X, стр. 246-247.

- Dimitar Bechev, Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Edition 2, Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, ISBN 1538119625, p. 11.

- Poparsov was Bulgarian teacher between 1892-1897; 1903-1904; 1910 and 1914-1929. For more see: Воин Божинов, Българската просвета в Македония и Одринска Тракия 1878-1913, Българска академия на науките, София, 1982, стр. 100.

- In Macedonia, the education race produced the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), which organized and carried out the Ilinden Uprising of 1903. Most of IMRO’s founders and principal organizers were graduates of the Bulgarian Exarchate schools in Macedonia, who had become teachers and inspectors in the same system that had educated them. Frustrated with the pace of change, they organized and networked to develop their movement throughout the Bulgarian school system that employed them. The Exarchate schools were an ideal forum in which to propagate their cause, and the leading members were able to circulate to different posts, to spread the word, and to build up supplies and stores for the anticipated uprising. As it became more powerful, IMRO was able to impress upon the Exarchate its wishes for teacher and inspector appointments in Macedonia. For more see: Julian Brooks, The Education Race for Macedonia, 1878—1903 in The Journal of Modern Hellenism, Vol 31 (2015) pp. 23-58.

- Initially the membership in BMARC was restricted per Art. 3 from its statute only for Bulgarians: The revolutionary committee dedicated itself to fight for "full political autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople." Since they sought autonomy only for those areas inhabited by Bulgarians, they denied other nationalities membership in IMRO. According to Article 3 of the statutes, "any Bulgarian could become a member". For more see: Laura Beth Sherman, Fires on the mountain: the Macedonian revolutionary movement and the kidnapping of Ellen Stone, Volume 62, East European Monographs, 1980, ISBN 0914710559, p. 10.

- The almost exclusive “national” basis of the Internal organization was namely the Bulgarian Exarchist population. The same holds true for the clear domination of the Exarchist social elite within its leadership and of the practical support given to it by the local institutions of the Bulgarian Exarchate. Bulgarian teachers in Macedonia constituted the backbone of the Internal organization while, according to their social profile, its leaders were quite often themselves Exarchist teachers... The lack of diverse ethnic motivations is confirmed by the fact that, in his brochure "Stambolovism in Macedonia and its representatives" issued in 1894, Poparsov generally used the designations “Bulgarian Macedonians” and “Macedonian Bulgarians” in order to name his “compatriots.” For more see: Tchavdar Marinov We, the Macedonians. The Paths of Macedonian Supra-Nationalism (1878–1912) p. 107-137 in We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe with Mishkova Diana as ed., Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289.

- According to Poparsov the main reason for the establishment of the Internal organization was the brutal politics of Serbianization of the Macedonian Bulgarians, which denied all human dignity to them, and brutally hurt their Bulgarian national feelings, clearly patronized by the representatives of the Russian Tsar and actively assisted by the Turkish sultan's government, artificially creating affairs and tying the Bulgarians to prisons and exiles, creating in the souls of this millions of Bulgarians a tragedy that became even more terrible, given that Serbianization meant not only denationalization, but also put the Macedonian Bulgarians back under the authority of the Greek Patriarchate, against which they had fought a long struggle. For more see: ВМОРО през погледа на нейните основатели. Спомени на Дамян Груев, д-р Христо Татарчев, Иван Хаджиниколов, Антон Димитров, Петър Попарсов. Съст. Т. Петров, Ц. Билярски. София, 2002, с. 203-207.

- The origins of the official Macedonian national narrative are to be sought in the establishment in 1944 of the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. This open acknowledgment of the Macedonian national identity led to the creation of a revisionist historiography whose goal has been to affirm the existence of the Macedonian nation through the history. Macedonian historiography is revising a considerable part of ancient, medieval, and modern histories of the Balkans. Its goal is to claim for the Macedonian peoples a considerable part of what the Greeks consider Greek history and the Bulgarians Bulgarian history. The claim is that most of the Slavic population of Macedonia in the 19th and first half of the 20th century was ethnic Macedonian. For more see: Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 0275976483, p. 58; Victor Roudometof, Nationalism and Identity Politics in the Balkans: Greece and the Macedonian Question in Journal of Modern Greek Studies 14.2 (1996) 253-301.

- Yugoslav Communists recognized the existence of a Macedonian nationality during WWII to quiet fears of the Macedonian population that a communist Yugoslavia would continue to follow the former Yugoslav policy of forced Serbianization. Hence, for them to recognize the inhabitants of Macedonia as Bulgarians would be tantamount to admitting that they should be part of the Bulgarian state. For that the Yugoslav Communists were most anxious to mold Macedonian history to fit their conception of Macedonian consciousness. The treatment of Macedonian history in Communist Yugoslavia had the same primary goal as the creation of the Macedonian language: to de-Bulgarize the Macedonian Slavs and to create a separate national consciousness that would inspire identification with Yugoslavia. For more see: Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- The first name of the IMRO was "Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees", which was later changed several times. Initially its membership was restricted only for Bulgarians. It was active not only in Macedonia but also in Thrace (the Vilayet of Adrianople). Since its early name emphasized the Bulgarian nature of the organization by linking the inhabitants of Thrace and Macedonia to Bulgaria, these facts are still difficult to be explained from the Macedonian historiography. They suggest that IMRO revolutionaries in the Ottoman period did not differentiate between ‘Macedonians’ and ‘Bulgarians’. Moreover, as their own writings attest, they often saw themselves and their compatriots as ‘Bulgarians’ and wrote in Bulgarian standard language. For more see: Brunnbauer, Ulf (2004) Historiography, Myths and the Nation in the Republic of Macedonia. In: Brunnbauer, Ulf, (ed.) (Re)Writing History. Historiography in Southeast Europe after Socialism. Studies on South East Europe, vol. 4. LIT, Münster, pp. 165-200 ISBN 382587365X.

- The modern Macedonian historiographic equation of IMRO demands for autonomy with a separate and distinct national identity does not necessarily jibe with the historical record. There is an issue of what autonomy meant to the people who espoused it in their writings. According to one of its founders - Hristo Tatarchev, their demand for autonomy was motivated not by an attachment to Macedonian national identity, but out of concern that an explicit agenda of unification with Bulgaria would provoke other small Balkan nations and the Great Powers to action. Macedonian autonomy, in other words, can be seen as “Plan B” of Bulgarian unification. Another from the founders - Dame Gruev, claimed that Macedonian Slavs are Bulgarians and they always have worked and will work for the unification of the whole Bulgarian nation and the autonomy was a stage to achieve this goal. On the other hand, according to Poparsov, the IMRO's position to stay away from Bulgaria, was not because the country was blamed for the plight of Macedonia, but because any suspicion of direct Bulgarian intervention into the IMRO's activity, could harm both Bulgarian and IMRO interests. For more see: İpek Yosmaoğlu, Blood Ties: Religion, Violence and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908, Cornell University Press, 2013, ISBN 0801469791, pp. 15-16 and Петров, Тодор, Билярски, Цочо, ВМОРО през погледна на нейните основатели, Военно издателство, София, 2002 г., стр.205; Dimitar Gotsev,"The idea of the autonomy as a tactic in the programs of the national liberation movements in Macedonia and Thrace, 1893-1941". Publishing House of Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, 1983, p. 18.

- Грага за историјата на македонскиот народ од Архивот на Србија. т. ІV, кн. ІІІ (1888-1889). Београд, 1987 и Т. V, кн. І (1890). Београд, 1988.

- The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization was inspired by Bulgarian freedom fighters... IMRO revolutionaries clearly saw themselves as the inheritors of Bulgarian revolutionary traditions and identified as Bulgarians. Jonathan Bousfield, Dan Richardson, Bulgaria, Rough Guides, 2002, ISBN 1858288827, p. 450.

- IMRO group modeled itself after the revolutionary organizations of Vasil Levski and other noted Bulgarian revolutionaries like Hristo Botev and Georgi Benkovski, each of whom was a leader during the earlier Bulgarian revolutionary movement. Duncan M. Perry, The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893-1903, Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0822308134, pp. 39-40.

- Mercia MacDermott, Freedom or Death. The Life of Gotsé Delchev, Journeyman Press, London & West Nyack, 1978, p. 99.

- По примерот на уставот на Бугарскиот револуционерен централен комитет, тие го подготвиле првиот устав на Македонската револуционерна организација...Нејзиниот прв основен програмски документ, бил публикуван во 1894 година под името „Устав на Бугарските македонско-одрински револуционерни комитети", а Организацијата, дури без и да се нарече организација, скратено ја нарекле БМОРК. Под официјалното име на БМОРК таа постоела неполни две години по нејзиниот основачки конгрес. Ова на свој начин го посведочува и П. Поп Арсов. Тој се смета за автор на првиот Устав. Manol D. Pandevski, Makedonskoto osloboditelno delo vo XIX i XX vek, Tom 1, Misla, 1987, str. 87.

- На втората средба, една од важните точки на дневниот ред најверојатно била донесувањето на уставот...На учесниците им се нашла при рака револуционерната литература од времето на бугарските револуционерни борби...Изработката на проект-уставот му била доверена на П Поп Арсов. На следните средби, шестмината го прифатиле уставот и ова бил нејзиниот прв акт... Има еден отпечатан устав коjшто носи наслов „Устав на Бугарските македонско-одрински револуционерни комитети", и за коj се тврди дека е првиот устав на Внатрешната организациjа. Крсте Битовски, Бранко Панов, Македонија во деветнаесеттиот век до Балканските војни (1912-1913), Том 3; Том 5, Институт за национална историја (Скопје, Македонија), 2003, ISBN 9989624763, стр. 162-163.

- Lambi V. Danailov, Stilian Noĭkov, Natsionalno-osvoboditelnoto dvizhenia v Trakija 1878-1903, Tom 2, Trakiĭski nauchen institut, Izd. na otechestvenia front, 1971, str. 81-82.

- Ристовский, Блаже. Димитрий Чуповский и македонское национальное сознание, ОАО Издательство „Радуга“, Москва, 1999, с. 76.

- Бруталната политика на посърбяване, която отричаше всяко човешко достойнство у македонските българи и жестоко нараняваше националното им чувство - създаде в душата на тоя милионен български народ една трагедия, която ставаше още по-страшна пред вид на това, че посърбяването означаваше не само денационализиране, ами и повръщане на македонските българи под ведомството на Гръцката патриаршия, против която бяха водили дългогодишна кървава борба и едва се бяха изкопчили от вампирските ѝ нокти. Лозунгът беше: далече от България! Не за това, че тя беше виновница за положението в Македония, ами защото всяко подозрение за нейна намеса можеше да напакости и ней, и на делото, което трябваше да си запази своя чисто вътрешен македонски характер. Върху тези ясни и точно определени основи се образува първия таен "Комитет за придобиване политическите права на Македония, дадени ѝ от Берлинския договор", от който сетне се разви тъй наречената Вътрешна М. Р. Организация..., в "Бюлетин на Временното представителство на обединената бивша Вътрешна македонска революционна организация", брой №8 от 19 юли 1919, стр. 2-3.