Phialemonium obovatum

Phialemonium obovatum is a saprotrophic filamentous fungus able to cause opportunistic infections in humans with weakened immune systems.[1][2][3] P. obovatum is widespread throughout the environment, occurring commonly in sewage, soil, air and water.[1][2] Walter Gams and Michael McGinnis described the genus Phialemonium to accommodate species intermediate between the genera Acremonium and Phialophora.[2][4][5][6] Currently, three species of Phialemonium are recognized of which P. obovatum is the only one to produce greenish colonies and obovate conidia.[7] It has been investigated as one of several microfungi with potential use in the accelerated aging of wine.

| Phialemonium obovatum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Subdivision: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. obovatum |

| Binomial name | |

| Phialemonium obovatum Gams, W. & McGinnis, M.R. (1983) | |

Growth and morphology

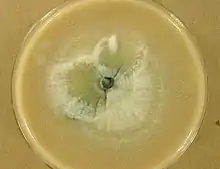

In culture, colonies of P. obovatum begin as white or off-white in colour becoming pale green and centrally darkened with age.[1][8] The green pigments diffuse into the growth medium ultimately becoming blackish-green in colour.[1] Although the hyphae of the fungus are typically colourless (hyaline), the presence of these dark diffusible pigments has resulted in this species being considered one of the dematiaceous (aka filamentous, darkly-pigmented) fungi.[8] This placement may be further justified by the confirmation of melanin pigments in hyphal walls and septa as demonstrated by Fontana-Masson's staining procedure.[2][6] These melanins are responsible for the slight dark coloration of hyphae and conidia as well as the dark colours seen in the center of the colonies.[8]

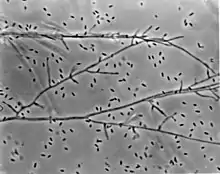

Gams and McGinnis described P. obovatum as having a flat, smooth colony texture with hyphal strands that radiate outwards described as floccose (fluffy or cottony).[4] Colonies of this species appear moist and lack a distinctive odour.[4] The fungus produces droplets of smooth-walled, obovate conidia with a narrow base. Their shape is similar to a tear drop or an egg-like shape.[1][6][7] Phialemonium obovatum conidia arise from adelophialides (phialides lacking a basal septum) that do not have a collarette.[4][7][6] Conidia are typically produced only at the interface of the medium surface and the air, and are rarely present on submerged or aerial hyphae.[4][7] Phialemonium obovatum grows optimally between 24–33 °C (75–91 °F) although it can grow at temperatures as low as 15 °C (59 °F) and as high as 40 °C (104 °F).[4]

Pathogenicity

Although P. obovatum is primarily thought to be saprotrophic, it can cause infections in human hosts under certain circumstances, and more rarely, of other animals notably dogs.[1][2][6][9] The capacity of Phialemonium obovatum to grow at and above human body temperature is a key pathogenicity factor of this species that distinguishes it from many other dematiaceous molds.[6] This species has been reported as a causative agent of endocarditis, keratitis, peritonitis, osteomyelitis, subcutaneous infections, and infections arising secondary to burns.[1][2][6][9] In case studies involving infections following severe burns, the hyphae of P. obovatum have the ability to invade into blood vessels and tissues.[7] Infections caused by this species are largely opportunistic and restricted to immunocompromised individuals with few cases reported from individuals with normally functional immune systems.[1][2][6][7] It has a proclivity to invade central nervous system tissues.[6] Given the rising population burden of immunocompromised people due to improved management of immunological diseases or mediate by therapeutic side effects, this and other agents of opportunistic disease are sometimes considered to be "emerging" agents of disease.[6] Accordingly, P. obovatum and other dematiaceous fungi have been increasingly reported in allogenic transplant recipients possibly as a consequence of chemotherapeutic immune suppression primarily intended to reduce tissue rejection.[9][6]

The sequestration of antioxidant materials in cells walls may also serve as a virulence factors for this agent.[6] A yeast-like phase has also been reported from the blood of infected individuals. P. obovatum can cause localized or disseminated infections the latter of which are occasionally fatal.[6]

Biotechnology

Colonization of wood by P. obovatum has been shown to produce syringol - a compound that is produced when the wood is heated, and guaiacol, a thermal decomposition product of lignin that is characterized by an oaky, burnt aroma.[10][11] Both compounds but particularly guaiacol are important contributors to the "oaked" flavour characteristics of barrel-aged wine.[10][11] Treatment of wines using wood chips inoculated with P. obovatum and other microfungi has been investigated as an accelerated, cost effective means of imparting oak flavours than traditional cask aging.[11]

References

- Hong, Kwon Ho; Ryoo, Nam Hee; Chang, Sung Dong (2012). "Phialemonium obovatum Keratitis after Penetration Injury of the Cornea". Korean Journal of Ophthalmology. 26 (6): 465–8. doi:10.3341/kjo.2012.26.6.465. PMC 3506823. PMID 23204804.

- Perdomo, H.; Sutton, D. A.; García, D.; Fothergill, A. W.; Gené, J.; Cano, J.; Summerbell, R. C.; Rinaldi, M. G.; Guarro, J. (2011-04-01). "Molecular and Phenotypic Characterization of Phialemonium and Lecythophora Isolates from Clinical Samples". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 49 (4): 1209–1216. doi:10.1128/JCM.01979-10. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 3122869. PMID 21270235.

- "Phialemonium obovatum". www.cbs.knaw.nl. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- Gams, Walter; McGinnis, Michael R. (1983-11-01). "Phialemonium, a New Anamorph Genus Intermediate between Phialophora and Acremonium". Mycologia. 75 (6): 977–987. doi:10.2307/3792653. JSTOR 3792653.

- "Phialemonium obovatum". www.mycobank.org. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- Gavin, Patrick J.; Sutton, Deanna A.; Katz, Ben Z. (2002-06-01). "Fatal Endocarditis in a Neonate Caused by the Dematiaceous Fungus Phialemonium obovatum: Case Report and Review of the Literature". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40 (6): 2207–2212. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.6.2207-2212.2002. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 130710. PMID 12037088.

- McGinnis, Michael R.; Gams, Walter; Goodwin, Malcolm N. (1986-01-01). "Phialemonium obovatum infection in a burned child". Journal of Medical and Veterinary Mycology. 24 (1): 51–55. doi:10.1080/02681218680000061. ISSN 0268-1218.

- Brandt, M.e.; Warnock, D.w. (2003-01-01). "Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Therapy of Infections Caused by Dematiaceous Fungi". Journal of Chemotherapy. 15 (Supplement-2): 36–47. doi:10.1179/joc.2003.15.Supplement-2.36. ISSN 1120-009X. PMID 14708965.

- Thomas Clark, MD; Gregory D. Huhn, MD; Craig Conover, MD; Salvatore Cali, MPH; Matthew J. Arduino, DrPH; Rana Hajjeh, MD; Mary E. Brandt, PhD; Scott K. Fridkin, MD (2006-11-01). "Outbreak of Bloodstream Infection With the Mold Phialemonium Among Patients Receiving Dialysis at a Hemodialysis Unit •". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 27 (11): 1164–1170. doi:10.1086/508822. JSTOR 10.1086/508822. PMID 17080372.

- Petruzzi, Leonardo; Bevilacqua, Antonio; Ciccarone, Claudio; Gambacorta, Giuseppe; Irlante, Giuseppina; Pati, Sandra; Sinigaglia, Milena (2010-12-01). "Use of microfungi in the treatment of oak chips: possible effects on wine". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 90 (15): 2617–2626. doi:10.1002/jsfa.4130. ISSN 1097-0010. PMID 20718033.

- "Using Fungi-Treated Oak Chips to Increase the Extraction of Oak Character into Aging Wines". The Academic Wino. 2011-12-20. Retrieved 2015-11-17.