Pictorial map

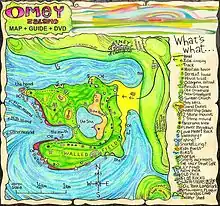

Pictorial maps (also known as illustrated maps, panoramic maps, perspective maps, bird’s-eye view maps, and geopictorial maps) depict a given territory with a more artistic rather than technical style.[1] It is a type of map in contrast to road map, atlas, or topographic map. The cartography can be a sophisticated 3-D perspective landscape or a simple map graphic enlivened with illustrations of buildings, people and animals. They can feature all sorts of varied topics like historical events, legendary figures or local agricultural products and cover anything from an entire continent to a college campus.[2] Drawn by specialized artists and illustrators, pictorial maps are a rich, centuries-old tradition and a diverse art form that ranges from cartoon maps on restaurant placemats to treasured art prints in museums.

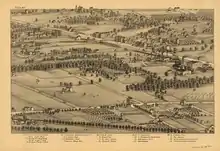

Pictorial maps usually show an area as if viewed from above at an oblique angle. They are not generally drawn to scale in order to show street patterns, individual buildings, and major landscape features in perspective. While regular maps focus on the accurate rendition of distances, pictorial maps enhance landmarks and often incorporate a complex interplay of different scales into one image in order to give the viewer a more familiar sense of recognition. With an emphasis on objects and style,[3] these maps cover an artistic spectrum from childlike caricature to spectacular landscape graphic, with the better ones being attractive, informative and highly accurate. Some require thousands of hours to produce.

The history and tradition of pictorial maps

Will Durant said that maps show us the face of history. Pictorial maps have been used to show the cuisine of a country, the industries of a city, the attractions of a tourist town, the history of a region or its holy shrines.

The history of pictorial maps overlaps much with the history of cartography in general,[1] and ancient artifacts suggest that pictorial mapping has been around since recorded history began.

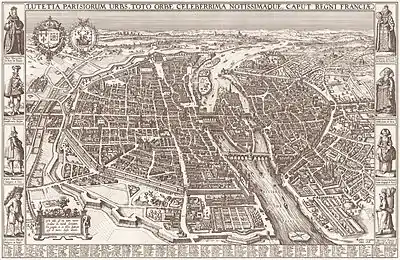

In Medieval cartography, pictorial icons as well as religious and historical ideas usually overshadowed accurate geographic proportions. A classic example of this is the T and O map, which represented the three known continents in the form of a cross, with Jerusalem at its center. The more precise art of illustrating detailed bird’s-eye-view urban landscapes flourished during the European Renaissance. As emerging trade centers such as Venice began to prosper, local rulers commissioned artists to develop pictorial overviews of their towns to help them organize trade fairs and direct the increasing flow of visiting merchants. When printing came around, pictorial maps evolved into some of the earliest forms of advertising as cities competed amongst themselves to attract larger shares of the known world’s commerce.

Later, during the Age of Exploration, maps became progressively more accurate for navigation needs and were often sprinkled with sketches and drawings such as sailing ships showing the direction of trade winds, little trees and mounds to represent forests and mountains and, of course, plenty of sea creatures and exotic natives, much of them imaginary. As the need for geographical accuracy increased, these illustrations gradually slipped off the map and onto the borders and eventually disappeared altogether in the wake of modern scientific cartography.

The 19th century

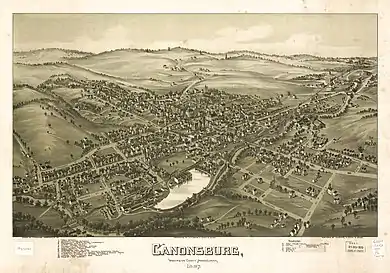

As cartography evolved, the pictorial art form went its own way and regained popularity in the 19th century with the development of the railroads. Between 1825 and 1875, the production and collection of panoramic maps of cities rose to something of a mania. In the U.S. alone, thousands of panoramic maps were produced. The leading panoramic map artists in the U.S.A. were Herman Brosius, Camille N. Drie, Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler, Paul Giraud, Augustus Koch, D. D. Morse, Henry Welge, and A. L. Westyard.[4][5] Somewhat like the websites of their time, every town sought to have one to remain competitive in attracting industry and the immigrant trade. Sometimes artistic exaggeration bordered on the fraudulent, as some travelers were drawn by images of idyllic, bustling towns with humming factories only to find a sad little bunch of mud-soaked shacks when they got there. A vast collection of these prints is maintained by the Library of Congress, and many of the more beautiful ones continue to be reprinted and sold to this day.[6]

The 20th century

With the growth of tourism, pictorial mapmaking reappeared as a popular culture art form in the 1920s through the 1950s, often with a whimsical Art Deco style that reflects the period.

Another resurgence occurred in the 1970s and 80s. This was the heyday of companies like Archar and Descartes who produced hundreds of colorful promotional maps of mainly American and Canadian cities. Local businesses were flatteringly drawn on these 'Character maps' with their logos proudly embedded on their buildings.

Pictorial map-makers up to modern times

Ironically, despite all the changes that they record, very little has changed in the business of creating pictorial maps over the centuries. Showing off a given town, attracting visitors and stirring up local pride is what they have always been about. Most of these maps were and continue to be created by a handful of itinerant specialists who keep up the tradition. Many of them traveled from city to city enlisting the support of local merchants, industrialists and civic organizations, whose endorsement would of course guarantee a prominent place for their properties on the map.

Edwin Whitefield for instance, one of the more prolific 19th-century American pictorial map artists, would require about 200 subscribers before he put pen to paper. Once he secured the profitability of the venture, Whitefield would be seen all over town furiously sketching every building. Then, choosing an imaginary aerial vantage point, he would integrate all his sketches into a complete and detailed drawing of the city. Then after that, say the chroniclers of the time, Whitefield would once again be seen furiously darting all over town to collect from all his sponsors. Says Jean-Louis Rheault, a contemporary pictorial map illustrator: "Pictorial maps - with their emphasis on what's important and eye-catching - make it easier to figure out what's where."[7]

Anthropomorphic maps

A type of pictoral maps are maps that use anthropomorphic images. Anthropomorphic maps date back to when Sebastian Münster used a queen to depict Europe in 1570.[8] The map, The Man of Commerce, by Augustus F. McKay is the earliest anthropomorphic map known of in the United States, created in 1889.[8]

See also

- Aerial photography – Taking images of the ground from the air

- Animated mapping – The application of animation to add a temporal component to a map displaying change

- Bird's-eye view – Elevated view of an object from above

- British Cartographic Society

- Cartogram – Map in which geographic space is distorted based on the value of a thematic mapping variable

- Terrain cartography, also known as Cartographic relief depiction

- Cartographic generalization

- Contour line

- Critical cartography – Mapping practices and methods of analysis grounded in critical theory

- Digital Cadastral DataBase

- Fantasy map – A visual representation of an imaginary or fictional geography

- Figure-ground in map design

- Four color theorem – Statement in mathematics

- Gazetteer – Geographical dictionary or directory used in conjunction with a map or atlas

- Geocode – Code that represents a geographic entity (location or object)

- Geographic Information System – System to capture, manage and present geographic data (GIS)

- Geovisualization

- Here be dragons – Phrase used on maps to indicate uncharted areas

- Isostasy – State of gravitational equilibrium between Earth's crust and mantle

- List of Japanese map symbols – Wikipedia list article

- List of cartographers – Wikipedia list article

- Locator map – Simple map used in cartography to show the location of a particular geographic area within its larger and presumably more familiar context;can be used on its own or as an inset or addition to a larger map

- Map projection – Systematic representation of the surface of a sphere or ellipsoid onto a plane

- National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- OpenStreetMap – Collaboratively edited world map available under free Open Database License, a free project mapping the world's roads using GPS

- Orthophoto

- Planetary cartography – Cartography of solid objects outside of the Earth

- Point of beginning – A surveyor's mark at the beginning location for the wide-scale surveying of land

- Sea level – Geographical reference point

- Terra incognita – 'Unknown land', area not mapped by cartographers

References

- "Mapas pictóricos, joyas ilustradas". Geogragift (in Spanish). Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- Glazer, George; Glazer, Helen. "About Pictorial Maps". New York: George Glazer Gallery. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- "Making Pictorial Maps". Sheffield: The Geographical Association. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- http://www.birdseyeviews.org/artist_bios.php

- "Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1902". World Digital Library. 1902. Retrieved 2013-06-03.

- Panoramic Maps Collection

- 'Map offers warped beautiful view of Bayview Cemetery'.The Bellingham Herald March 23rd 2009

- "The Man of Commerce". World Digital Library. 1889. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

Further reading

- J. B. Harley and David Woodward (eds) (1987). The History of Cartography Volume 1: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-31633-5.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Monmonier, Mark (1991). How to Lie with Maps. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-53421-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pictorial maps. |

- Pictorial Map Collection, St. Louis Public Library Digital Collections

- 1936 Pictorial Map of London

- Historic Cities

- History of Cartography

- Mapping History

- Panoramic maps, Library of Congress

- See Pictorial Maps in Persuasive Cartography, The PJ Mode Collection, Cornell University Library

- Bird's Eye View Map of Budapest