Pierre A. Riffard

Pierre A. Riffard is a French philosopher and specialist in esotericism. Born in Toulouse (France), he is a professor of pedagogy and philosophy at the University of the French West Indies and Guiana (Université des Antilles et de la Guyane). Teaching in the French overseas departments and territories and elsewhere: Asia, Oceania, Sub-Saharan Africa, Guiana.

Esotericism

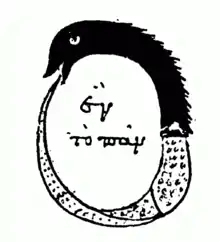

For Pierre A. Riffard, esotericism is "occult teaching, doctrine or theory, technique or process, of symbolic expression, of a metaphysical nature, of initiatory intent. Druidism, compagnonnage (the traditional French system of training craftsmen), alchemy are esotericisms."[1]

Pierre A. Riffard defended a Doctor of Philosophy thesis on the Greek formula ἓν καὶ πᾶν (hen kai pān, "the One and the All"), then a Doctor of Arts thesis on L'Idée d'ésotérisme [The Idea of Esotericism] (Paris 1 Sorbonne University, 1987), after conducting research into occultism. Author of the Dictionnaire de l'ésotérisme [Dictionary of Esotericism] (Payot, 1983), which is an authoritative work in the field, he has also written two sizeable volumes for the "Bouquins" collection of France's Editions Robert Laffont publishing house; one is devoted to esotericism in general: L'ésotérisme. Qu'est-ce que l'ésotérisme ? [Esotericism. What is Esotericism?], 1990; the other treats with non-Western esotericisms: Ésotérismes d'ailleurs [Esotericisms from other lands], 1997. As soon as 87, he proposed nine invariants for defining an esotericism:[2]

- the discipline of the arcane (keeping the secret). New Testament: "Do not give dogs what is sacred; do not throw your pearls to pigs. If you do, they may trample them under their feet, and then turn and tear you to pieces."[3]

- the impersonality of the author (showing the superhuman aspect of the message).

- the contrast between the esoteric and the exoteric (distinguishing the initiated from the uninitiated, the occult from the manifest).

- the subtle (admitting invisible or higher planes of reality: human aura, etheric body, astral influences, telluric waves, guardian angels, etc.). Alice Bailey: "Esotericism is a science, essentially the science of the soul of all things."[4]

- analogies and correspondences (comparing all the parts of the universe: macrocosm and microcosm, gums and fingers, blood and sap, colours and organs, animals and virtues, etc.).

- formal numbers (choosing symbolic arithmetic as the archetypal key: golden ratio, cosmic cycles, kabbalah of gematria, metres in poetry, rhythms in music, etc.). Pythagoras: "Things are numbers. ΄Ολα τα πράγματα είναι αριθμοί."[5]

- the occult arts (using alchemy, astrology, divination, magic, occult medicine).

- the occult sciences (hermeneutics, numerology, theosophy, the study of the afterlife, paradoxography (the cataloguing of wondrous phenomena), etc.).

- lastly, and above all, initiation (seeking improvement, spiritual liberation for others, for oneself or rather for the SELF).

In other terms,

- "An esotericism is teaching which takes the form of a secret doctrine or of an initiatory organisation, a spiritual practice or an occult art."[6]

As regards form, esotericists have a secret: paralipsis (apophasis). They purport to say nothing, while at the same time discreetly revealing something (In saying "I will say nothing about the sacred nature of sexuality", I have said that sexuality does indeed have a sacred nature). For example, symbols such as the apple or the coiled serpent reveal numerous clues or keys to sexuality, while simultaneously appearing to obfuscate the discourse or image.

As regards content, esotericists have another secret: reversion. They reverse ordinary ideas, they turn around commonplace behaviour, they overturn shared emotions, to return to the original. For example, kundalini yoga sends sexual energy up to the brain, and the alchemist returns to primary matter, when everything becomes possible and powerful again.

As regards sense, esotericists have no secrets; they just adopt a lifestyle, one which gives priority to the interior of things. For example, in love they prefer a state of consciousness higher than sexual pleasure; in alchemy they are more interested in the solar image of gold than its market value. "Riffard's approach may thus be characterized as universalist, religionistic, and trans-historical: Esotericism is a basic 'anthropological structure' and as such not dependent on cultural mediation. Its scope in time and space includes the whole of human history." -Wouter J. Hanegraaff.[7]

Philosophy

Pierre A. Riffard recently published essays examining the lifestyle of philosophers from a psychological and sociological point of view (Les philosophes: vie intime ["Philosophers: private life"], 2004; Philosophie matin, midi et soir ["Philosophy morning, noon and night"], 2006. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France). In Les philosophes: vie intime, he draws attention to some of the philosopher's human traits, which are not generally mentioned, covering everyone from Thales to Sartre:[8]

- a handicap: being female. Only one woman philosopher (Hannah Arendt) featured on an official list of 305 classical philosophers compiled in 1991.

- an opportunity: being an expatriate. More than 13% of philosophers are born outside their parent's home country, in the colonies. More than 54% of philosophers have lived abroad. Aristotle was born in Macedonia. Descartes spent 20 years in Holland.

- an advantage: being an orphan. 68% of major philosophers are orphaned by the age of five.

- no precociousness. As a statistical average, the first work is published at the age of 27, the masterpiece at the age of 42. Kant was already 57 years old when he published his masterpiece, The Critique of Pure Reason

- acceptance of the culturally dominant language. It is necessary to speak a scholarly language. 23% of major philosophers have written Latin (until 1905 in France), 21% Greek and French, 13% English (this is becoming the dominant language).

- rejection of the ideologically dominant religion. One enters philosophy in the same way that one enters the Mafia, by committing an assassination, of the God of the time, the beliefs of the time. The major philosophers are 51% Christian, 27% without religion and 19% pagan.

- clumsiness in matters of the heart. The glories of love are not on the agenda for philosophers (apart from Auguste Comte). Giordano Bruno: "Truly, with respect to that sex [the female sex], what I abominate is that zealous and disordered venereal love which some are accustomed to expend for it, so that they come to the point of making their wit the slave of woman, and of degrading the noblest powers and actions of the intellectual soul."[9]

- the risk of madness. A good philosopher keeps his insanity in check: Heraclitus' melancholia, Auguste Comte's manic-depression, Hegel's anxiety, Jean-Jacques Rousseau's paranoia, Nietzsche's syphilitic meningoencephalitis, etc.

- triumph over illness. Many philosophers suffer, but overcome, whether it be nephritis (Epicurus), kidney stones (Montaigne), paralysis (Blaise Pascal, Feyerabend), poor eyesight (Democritus, Plotinus, Condillac, Cournot, Gonseth), etc.

- obscure identities. Philosophers play around a lot with pen names, anonymity, etc. Descartes and Kierkegaard advance in disguise.

- a mixed bag of curriculum vitae. 43,7% of philosophers have been teachers, the rest have been members of the clergy (20,9%), politicians (9,3%), without profession (4,9%), doctors (4%), lawyers or jurists (3,1%), editors or journalists (3,1%), none or almost none have been artisans (Henry David Thoreau), farmers (Gustave Thibon) or sailors (Michel Serres).

- feet! Aristotelian = περιπατητικός, peripatetic = "walking". Nietzsche: "All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking."[10]

- and, of course, a head (one head or two, or three, if the philosopher changes philosophy, like Schelling, Wittgenstein, Carnap). A major philosopher shows themselves to the world as such thanks to their vast personal semantic memory and a universal metaphysical obsession. About Leibniz, we know that "his memory was so strong, that in order to fix anything in it, he had no more to do but to write it once", and he was obsessed by harmony.

- "Philosophy is like a nutcracker. There are some who merely end up pinching their fingers in it, professionals who are completely comfortable using it, and then there are people who use it to open those marvellous nuts called thoughts. To philosophise is good; to philosophise oneself is better. To philosophise oneself each day, on the routine, the commonplace, is best."[11]

"Pierre Riffard's vision of philosophy is that of a being torn between opposing demands: analysis and synthesis, the singular and the universal, certainty and doubt." ("La vision qu'a Pierre Riffard du philosophe est celle d'un être tiraillé par des sollicitations contraires : analyse et synthèse, le singulier et l'universel, certitude et doute.") -Thomas Régnier.[12]

Thanatology

Thanatology is the study of death among human beings.

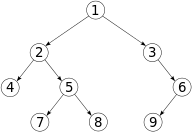

Raising the issue of the afterlife is no plain matter, something like “I believe in Paradise”. It actually is a speculative strategy, a rational reckoning, combining several concepts and requiring a number of successive choices.[13] It looks like a decision tree!

As for the afterlife itself, several problems arise. First of all, problems of method.

1 – Is it possible to ascertain whether there is an afterlife (or life after death) : yes (1a), maybe (1b), no (1c) ?

2 – Where is documentation to be found?

3 – What is to be considered as suitable evidence?

Next come the philosophical queries.

A - Should one negate (A1) or assert (A2) or suspend one’s opinion (A3) on the afterlife ?

B – Who survives : a single individual (B1), an elite (B2), a community (B3), Humanity (B4), the World (B5) ?

C - What survives : the soul (C1), a soul, the mind, the Self... ?

D- Under what shape : some specific element in the individual, some universal element... ?

E – Since when : the death of the individual, Doomsday... ?

F – Over what span of time : eternity ?

G – What type of time : cyclical, over an evolutionary period... ?

H – Where : a subterranean place, Heaven... ?

I – Following which law : God’s Will, Chance, One’s karma... ?

J – What types of survival : reincarnation, resurrection... ?

K – to what ultimate end : fusing into God, dissolution of the Self... ?

The Christian view of life after death is a combination of assertions : "the afterlife is a fact"(A2), humanity is concerned (B4), spiritualism (C1), Doomsday (E2)... and resurrection Skepticism and scientism bring reflection to an abrupt ending through the suspension of judgment (A3), it agrees with Wilder Penfield’s words : "Whether energy can come to the mind of man from an outside source after his death is for each individual to decide for himself. Science has no such answer" (The Mystery of the Mind, 1976).

All things considered, about a dozen ascertained types of survival are possible; they may either co-exist or follow one another and may vary according to the individuals, the souls, the actions. The history of religions mainly highlights a few types : neutral form of life (ex : the limbo in the Roman Catholic faith), shadow existence (Homer and the Ancient Jews), demonic life, damnation or salvation, migration of the souls through metempsychosis (whether the soul takes the shape of an animal or a plant or a human being) or reincarnation (in the human body's shape), catasterisation (transfer of the souls to the stars), palingenesis (one does not die but undergoes some transformation, just like mould turning into fungi), eternal return (all souls living through the same experiences again, thousands of years later, through cosmic palingenesis).

- "La mort selon Leibniz", Paris: Thanatologie, n° 83-84, 1990. Death according to Leibniz.

- "Comment se pose rationnellement le problème de la vie après la mort", Thanatologie, n° 87-88, novembre 1991. On afterlife.

- "La mort selon Steiner", Thanatologie, n° 89-90, avril 1992. Death according to Rudolf Steiner.

- "La mort selon Platon", Thanatologie, n° 97-98, avril 1994. Death according to Plato.

- "La mort selon Descartes", Études sur la mort, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (PUF), n° 114, 1998, 97-112. Death according to Descartes.

- 23 articles in Philippe Di Folco (dir.), Dictionnaire de la mort [Dictionary of Death], Paris: Larousse, coll. "In Extenso", 2010. "Astrology", "Descartes", "doppelgänger", "Epicurus", "esotericism"…

- "L'après-vie est-elle sexuée et sexuelle ?", Thanatologie, n° 147, 2015, p. 27-38.

Books by Pierre Riffard

- L'Occultisme, textes et recherches, Paris: Larousse, coll. "Idéologies et sociétés", 1981, 191 p. ISBN 2-03-861028-2.

- Dictionnaire de l'ésotérisme, Paris: Payot, coll. "Bibliothèque scientifique", 1983, 387 p. ISBN 2-228-13270-5 ; repr. coll. "Grande bibliothèque Payot", 1993, 387 p. ISBN 2-228-88654-8.

- L'Ésotérisme : Qu'est-ce que l'ésotérisme ?, Paris : Robert Laffont, coll. "Bouquins", 1990, 1016 p. ISBN 2-221-05464-4. Repr. 2003.

- Ésotérismes d'ailleurs. Les ésotérismes non occidentaux : primitifs, civilisateurs, indiens, extrême-orientaux, monothéistes, Paris: Robert Laffont, coll. "Bouquins", 1997, 1242 p. ISBN 2-221-07354-1.

- "The Esoteric Method", in Antoine Faivre and Wouter J. Hanegraaff (eds.), Western Esotericism and the Science of Religion, Leuven: Peeters, coll. "Gnostica", 1998, Xvii/309 pages, 63-74.

- "Le penser ésotérique", "Existe-t-il un ésotérisme négro-africain ?", and "Descartes et l'ésotérisme", ARIES. Association pour la Recherche et l'Information sur l'Esotérisme, Paris: Archè, n° 21, 1998, p. 1-28, 197-203. ISBN 88-7252-192-0.

- Les philosophes : vie intime, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (PUF), coll. "Perspectives critiques", 2004, 283 p. ISBN 2-13-053968-8.

- "Non-philosophe : ce n'est pas moi c'est toi", in Gilles Grelet (dir.), Théorie-rébellion, Paris: L'Harmattan, coll. "Nous les sans-philosophie", 2005, 42-45. ISBN 2-7475-9210-3.

- "La transmission des savoirs ésotériques" (Université Laval, 2006)

- Philosophie matin, midi et soir, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (PUF), coll. "Perspectives critiques", 2006, 185 p. ISBN 2-13-055735-X.

- Nouveau dictionnaire de l'ésotérisme, Paris: Payot, 2008, 331 p. ISBN 978-2-228-90274-8.

- "Qu'est-ce qu'une méthode (philosophique ou pas) ?", Revue internationale de didactique de la philosophie, CRDP Montpellier, #46 (oct. 2010).

- "Les méthodes des grands phılosophes", Ovadia, coll. "Chemıns de pensée", 2012, 331 p. ISBN 2363920368

- La vie après la mort, Bouquins, "La collection", 2021, 1184 p. (avec Élisabeth Andrès et Gilbert Pons). ISBN 9-782221-131206

See also

- Afterlife

- Esotericism

- Occult

- Non-philosophy

- Thanatology

External links

Notes and references

- P. Riffard, Dictionnaire de l'ésotérisme, Paris: Payot, 1983, 125.

- P. Riffard, L'ésotérisme. Qu'est-ce que l'ésotérisme ? Anthologie de l'ésotérisme occidental, Paris: Robert Laffont, coll. "Bouquins", 1990, 245-396.

- Saint Matthew, VII, 6.

- Alice Bailey, Education in the New Age, New York / London: Lucis Trust, 1954, 64.

- Pythagoras in Aristotle, Metaphysics, A, 6, 987b28.

- P. Riffard, Nouveau dictionnaire de l'ésotérisme, Paris: Payot, 2008, 96.

- Wouter J. Hanegraaff, "On the Construction of Esoteric Traditions", in Antoine Faivre and Wouter J. Hanegraaff (eds.), Western Esotericism and the Science of Religion, Leuven: Peeters, coll. "Gnostica", 1998, 24, 60.

- P. Riffard, Les philosophes: vie intime, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (PUF), 2004, 33-232.

- Giordano Bruno, The Heroic Frenzies (1585), argument. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964.

- Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols (1888), I, 34.

- P. Riffard, Philosophie matin, midi et soir, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (PUF), 2006, 177.

- Thomas Régnier, "Un essai de Pierre Riffard. La philomafia", Paris: Le Nouvel Observateur, n° 2228, 1-7 avril 2004, 108.

- Pierre A. Riffard, « Comment se pose rationnellement la question de la vie après la mort », Thanatologie, Paris: Société de thanatologie, 87/88 (1991), 99-108 ; « Vie après la mort », in Philippe Di Folco (dir.), Dictionnaire de la mort, Paris: Larousse, 2010, 1075-1078.