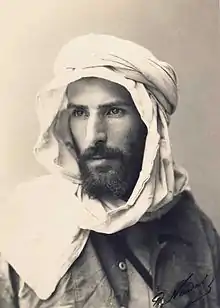

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza

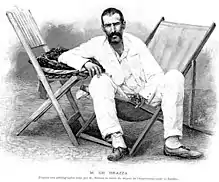

Pietro Paolo Savorgnan di Brazzà, later known as Pierre Paul François Camille Savorgnan de Brazza; 26 January 1852 – 14 September 1905[1]), was an Italian naturalized French explorer. With the financial help from his Italian family, he explored th Ogoué region of Central Africa, and later with the backing of the Société de Géographie de Paris, he reached far into the interior along the right bank of the Congo. His friendly manner, great charm and peaceful approach made him among Africans. Under French colonial rule, the capital of the Republic of the Congo was named Brazzaville after him and the name was retained by the post-colonial rulers, the only African nation to do so.

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza | |

|---|---|

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza photographed by Paul Nadar | |

| Born | January 26, 1852 |

| Died | September 14, 1905 (aged 53) |

| Nationality | Italian born, French naturalized, hence his name "Pierre" |

| Occupation | Explorer |

| Spouse(s) | Thérèse Pineton de Chambrun |

| Children | Jacques, Antoine, Charles, Marthe |

| Relatives | Adolphe de Chambrun (father-in-law) Pierre de Chambrun (brother-in-law) Charles de Chambrun (brother-in-law) René de Chambrun (nephew) |

Early years

Born in Rome, Pietro Savorgnan di Brazzà was the seventh of thirteen children. His father Ascanio Savorgnan di Brazzà, was a nobleman and well known artist, from a family with ancient Friulan origins and many French connections. His mother Giacinta Simonetti, from an old Roman family with Venetian roots, was 24 years younger then his father. From an early age, Pietro was interested in explorations, particularly in West Africa, and won entry to the French naval school Academy of Borda at Brest.[2] In 1870, he graduated and sailed aboard the French ship Jeanne d'Arc to Algeria, where he witnessed the bloody crushing of the Mokrani Revolt.[2] This committed him to a philosophy of non-violence throughout his life.

Exploration in Africa

Brazza first encountered Africa in 1872, while sailing on an anti-slavery mission near Gabon.[3] His next ship was the Vénus, which stopped at Gabon regularly. In 1874 Brazza made two trips into the interior, up the Gabon and Ogooué rivers. He then proposed to the government that he explore the Ogooué to its source. With the help of friends in high places, including Jules Ferry and Leon Gambetta, he secured partial funding, the rest coming from his own pocket. He was granted French citizenship in 1874,[4] and adopted the French spelling of his name. His efforts to gain citizenship had been aided by Louis Raymond de Montaignac de Chauvance, who acted as de Brazza's patron in the early years of his career.[2]

In this expedition, which lasted from 1875–1878, 'armed' only with cotton textiles and tools to use for barter, and accompanied by Noel Ballay, a doctor, naturalist Alfred Marche, a sailor, thirteen Senegalese laptots and four local interpreters, Brazza charmed and talked his way deep inland. Upon his return to Paris he was fêted as a celebrity in the French press and was courted by the French political elite as the man to advance their imperialist ambitions in Africa.[5] The French authorized a second mission, which was carried out 1879-1882. The French had adjudged his first mission a success and felt that a mission to the Congo Basin was needed to prevent Belgium from occupying the entire area.[4] By following the Ogoué River upstream and proceeding overland to the Lefini River and then downstream, de Brazza succeeded in reaching the Congo River in 1880 without encroaching on Portuguese claims.[6]

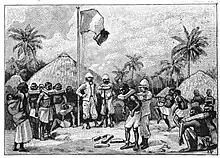

De Brazza then proposed to King Illoh Makoko of the Batekes that he place his kingdom under the protection of the French flag. Makoko, interested in trade possibilities and in gaining an edge over his rivals, signed the treaty.[7] The terms of this treaty were upheld after the king's death by his queen, Ngalifourou, who became Queen Mother and an influential figure in french colonial life.[8] De Brazza respected Ngalifourou so much that he presented her with a sabre.[8] Makoko also arranged for the establishment of a French settlement at Mfoa on the Congo's Malebo Pool, a place later known as Brazzaville; after de Brazza's departure, the outpost was manned by two Laptots under the command of Senegalese Sergeant Malamine Camara, whose resourcefulness had impressed de Brazza during their several months together trekking inland from the coast. During this trip he encountered Stanley near Vivi. Brazza did not tell Stanley that he had just signed a treaty with Makoko; it took Stanley some months to realise that he had been beaten in the "race" set by his sponsor, King Leopold. Brazza was again celebrated in France for his efforts. The press dubbed him "le conquérant pacifique", the peaceful conqueror, for his success in ensuring French imperial expansion without waging war.[9]

In 1883,[10] De Brazza was named governor-general of the French Congo in 1886.[6] He was dismissed in 1897 due to poor revenue from the colony and journalist reports of conditions for the natives that some said were "too good." For his part Brazza had become somewhat disillusioned with the exploitative and repressive practices of the concessionary companies, which he had witnessed first-hand.[11]

De Brazza became a freemason in 1888. Initiated at the "Alsace-Lorraine" lodge in Paris, on June 26, 1888.[12][13][14]

By 1905, stories had reached Paris of injustice, forced labour and brutality under the laissez-faire approach of the Congo's new governor, Émile Gentil, to the new concession companies set up by the French Colonial Office and condoned by Prosper Philippe Augouard, Catholic Bishop of the Congo. Brazza was sent to investigate these stories and the resulting report was revealing and damning, in spite of many obstructions placed in his path. When his deputy Félicien Challaye put the embarrassing report before the National Assembly, the report was suppressed.

The oppressive conditions in the French Congo continued for decades.[15]

Personal life

Brazza married Thérèse de Chambrun.[16] As a result, Pierre de Chambrun and Charles de Chambrun were his brothers-in-law. Meanwhile, René de Chambrun, the son-in-law of Vichy France Prime Minister Pierre Laval, was his nephew.[16]

Death and memorials

The last tour of the Congo took a hard physical toll of Brazza, and on his return journey to Dakar he died of dysentery and fever, but his wife who was with him always mantained that he had been poisoned. His body was repatriated to France and he was given a state funeral at Sainte-Clotilde, Paris, prior to interment at the cemetery of Père Lachaise. His widow, Thérèse, dissatisfied with the politicians' subsequent behaviour, had his body exhumed and reinterred in Algiers (capital of present-day Algeria).[17] The epitaph for his burial site in Algiers reads: "une mémoire pure de sang humain" ("a memory untainted by human blood").

Brazzaville Mausoleum

In February 2005 Presidents Nguesso of Congo, Ondimba of Gabon and Chirac of France gathered at a ceremony to lay the foundation stone for a memorial to Pierre de Brazza, a mausoleum of Italian marble. On 30 September 2006, de Brazza's remains were exhumed from Algiers[18] along with those of his wife and four children.[19] They were reinterred in Brazzaville on 3 October in the new marble mausoleum which had been prepared for them and had cost some 10 million dollars. The ceremony was attended by three African presidents and a French foreign minister, who paid tribute to de Brazza's humanitarian work against slavery and the abuse of African workers.

Mausoleum controversy

The decision to honor Pierre de Brazza as a founding father of the Republic of the Congo has elicited protests among many Congolese. Mwinda Press, the journal of the Association of Congolese Democrats in France wrote articles quoting Théophile Obenga who depicted Pierre de Brazza as a colonizer and not a humanist, declaring him to have raped a Congolese woman, a princess and the equivalent of a Vestal Virgin, and to have pillaged villages, raising highly charged questions as to why the colonizer should be revered as a national hero instead of the Congolese who fought against colonization.[20]

Notes

- Pierre de Brazza at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Berny Sèbe (2015). Heroic Imperialists in Africa: The Promotion of British and French Colonial Heroes, 1870-1939. Oxford University Press. p. 304.

- "Vita - Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza".

- Hodge, Carl Cavanagh, ed. (2008). Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800-1914: A-K. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 106.

- Sèbe. Heroic Imperialists in Africa. p. 149.

- Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong, Henry Louis Gates, Dictionary of African Biography, Volume 6, OUP USA, 2012, p. 3

- Sèbe, Heroic Imperialists in Africa, p. 148

- jeremy, rich (2012), "Ngalifourou", Dictionary of African Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195382075.001.0001/acref-9780195382075-e-1533, ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5, retrieved 2021-01-16

- Mavor, Carol (2012). Black and Blue: The Bruising Passion of Camera Lucida, La Jetée, Sans Soleil, and Hiroshima Mon Amour. Duke University Press. p. 176.

- Histoire militaire des colonies, pays de protectorate et pays sous mandat. 7. "Histoire militaire de l'Afrique Équatoriale française". 1931. Accessed 9 October 2011. (in French)

- Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. p. 205.

- Daniel Ligou (2011). Dictionnaire de la Franc-maçonnerie (in French). Presses Universitaires de France. p. 163.

- Laurent Kupferman; Emmanuel Pierrat (2012). Ce que la France doit aux francs-maçons (in French). éditions Grund.

- Jean Massicot (2010). La franc-maçonnerie (in French). édition Desnoël. p. 26. Nevertheless in 1904 he resigned from the French maçonnerie for the responsibilities which it had in the management of the colony in the French Equatorial Africa.

- Sèbe, Heroic Imperialists in Africa, p. 305

- Pourcher, Yves (Spring 2012). "Laval Museum". Historical Reflections. 38 (1): 105–125. doi:10.3167/hrrh.2012.380108.

One day, the Count told me he had made a discovery of some papers that Josee had gathered about his parents, the Chambruns, and Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, his paternal uncle.

- Brazza’s death ministère de la culture et de la communication de France

- Africa explorer's remains exhumed, BBC News, 30 September 2006.

- African nation builds £1.4m marble mausoleum for colonial master, The Guardian, 4 October 2006

- Brea, Jennifer (9 October 2006). "Congo-Brazzaville: Should a Colonizer Be Honored Like a Founding Father?". Global Voices. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

References

- Maria Petringa, Brazza, A Life for Africa, Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2006, ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0

- Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa (1991)

- Richard West, Brazza of the Congo Victorian & Modern History Book Club (1973)

- Emanuela Ortis - "Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza: heròs du Friul" (2003) Radici n.9

- Théophile Obenga - Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza à la cour royale du Makoko,

- Congolese reaction to the Mausoleum controversy

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Brazza, Pierre Paul François Camille Savorgnan de. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pietro Savorgnan di Brazza. |

- "Final return to Congo". BBC News. 2006-09-23. Retrieved 2008-08-06., BBC News, 23 September 2006

- A site dedicated to Brazza's life and times (in French, Italian and English)

- Fondation Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza (in French)

- Maria Petringa's 1997 "Brief Life of a Lover of Africa", a short biography of Savorgnan de Brazza with one of Paul Nadar's famous photos of the explorer

- Congolese reaction to the Mausoleum controversy ( in French and English)

- Newspaper clippings about Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW