Pietro Aretino

Pietro Aretino (US: /ˌɑːrɪˈtiːnoʊ, ˌær-/,[1][2] Italian: [ˈpjɛːtro areˈtiːno]; 19 or 20 April 1492[3] – 21 October 1556) was an Italian author, playwright, poet, satirist and blackmailer, who wielded influence on contemporary art and politics. He was one of the most influential writers of his time and an outspoken critic of the powerful.[4]

Pietro Aretino | |

|---|---|

Pietro Aretino, in Titian's first portrait of him | |

| Born | 19 or 20 April 1492 Arezzo, Republic of Florence (present-day Tuscany, Italy) |

| Died | 21 October 1556 (aged 64) Venice, Republic of Venice (present-day Veneto, Italy) |

| Occupation | Author, playwright, poet, satirist |

| Nationality | Italian |

Life

His father was Luca Del Tura, a shoemaker from Arezzo, who abandoned his family to join the militia. The father later returned to Arezzo, finally dying in poverty at the age of 85, unforgiven by his son, who never acknowledged the paternal name, taking Aretino (that is 'Arretine, from Arezzo') as a surname.

His mother was Margherita, known as Tita, Bonci. Either before or after the abandonment (we do not know which), she entered into a lasting relationship with a local noble, Luigi Bacci, who supported Tita, Pietro and his two sisters and brought up Pietro as part of his own family.[5]

Aretino spent a formative decade in Perugia, before being sent, highly recommended, to Rome. There Agostino Chigi, the rich banker and patron of Raphael, took him under his wing.

When Hanno the elephant, pet of Pope Leo X, died in 1516, Aretino penned a satirical pamphlet entitled "The Last Will and Testament of the Elephant Hanno". The fictitious will cleverly mocked the leading political and religious figures of Rome at the time, including Pope Leo X himself. The pamphlet was such a success that it started Aretino's career and established him as a famous satirist, ultimately known as "the Scourge of Princes".

Aretino prospered, living from hand to mouth as a hanger-on in the literate circle of his patron, sharpening his satirical talents on the gossip of politics and the Papal Curia, and turning the coarse Roman pasquinade into a rapier weapon of satire, until his sixteen ribald Sonetti Lussuriosi (Lust Sonnets) written to accompany Giulio Romano's exquisitely beautiful but utterly pornographic series of drawings engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi under the title I Modi finally caused such outrage that he had to temporarily flee Rome.

After Leo's death in 1521, his patron was Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, whose competitors for the papal throne felt the sting of Aretino's scurrilous lash. The installation of the Dutch pope Adrian VI ("la tedesca tigna" in Pietro's words) instead encouraged Aretino to seek new patrons away from Rome, mainly with Federico II Gonzaga in Mantua, and with the condottiero Giovanni de' Medici ("Giovanni delle Bande Nere"). The election of his old Medici patron as Pope Clement VII sent him briefly back to Rome, but death threats and an attempted assassination from one of the victims of his pen, Bishop Giovanni Giberti, in July 1525, set him wandering through northern Italy in the service of various noblemen, distinguished by his wit, audacity and brilliant and facile talents, until he settled permanently in 1527, in Venice, the anti-Papal city of Italy, "seat of all vices", Aretino noted with gusto.

He was a lover of men, having declared himself "a sodomite" since birth. In a letter to Giovanni de' Medici written in 1524 Aretino enclosed a satirical poem saying that due to a sudden aberration he had "fallen in love with a female cook and temporarily switched from boys to girls..." (My Dear Boy). In his comedy Il marescalco, the lead man is overjoyed to discover that the woman he has been forced to marry is really a page boy in disguise. While at court in Mantua he developed a crush on a young man called Bianchino, and annoyed Duke Federico with a request to plead with the boy on the writer's behalf.[6]

Safe in Venice, Aretino became a blackmailer, extorting money from men who had sought his guidance in vice. He "kept all that was famous in Italy in a kind of state of siege",[7] in Jakob Burckhardt's estimation. Francis I of France and Charles V pensioned him at the same time, each hoping for some damage to the reputation of the other. "The rest of his relations with the great is mere beggary and vulgar extortion", according to Burckhardt. Addison states that "he laid half Europe under contribution".[8]

His literary talent, his clear and sparkling style, his varied observation of men and things, would have made him a considerable writer under any circumstances, destitute as he was of the power of conceiving a genuine work of art, such as a true dramatic comedy; and to the coarsest as well as the most refined malice he added a grotesque wit so brilliant that in some cases it does not fall short of that of Rabelais.

— Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, 1855.

Apart from both sacred and profane texts—a satire of high-flown Renaissance Neoplatonic dialogues is set in a brothel — and comedies such as La cortigiana and La talenta, Aretino is remembered above all for his letters, full of literary flattery that could turn to blackmail. They circulated widely in manuscript and he collected them and published them at intervals winning as many enemies as it did fame, and earned him the dangerous nickname Ariosto gave him: flagello dei principi ("scourge of princes"). The first English translations of some of Aretino's racier material have been coming onto the market recently.

La cortigiana is a brilliant parody of Castiglione's Il Cortegiano, and features the adventures of a Sienese gentleman, Messer Maco, who travels to Rome to become a cardinal. He would also like to win himself a mistress, but when he falls in love with a girl he sees in a window, he realizes that only as a courtier would he be able to win her. In mockery of Castiglione's advice on how to become the perfect courtier, a charlatan proceeds to teach Messer Maco how to behave as a courtier: he must learn how to deceive and flatter, and sit hours in front of the mirror.

Aretino was a close friend of Titian′s, who painted his portrait four times; two of the portraits survive, in the Frick Collection and in the Pitti Palace (illustration).[9] Titian also portrayed Aretino as Pontius Pilate in his painting ″Ecce Homo,″ in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna,[10] ″as a nameless soldier in the crowd″ in ″Allocution of Alfonso d'Avalos, Marchese del Vasto,″[11] and next to a self-portrait in ″La Gloria.″[12] Clement VII made Aretino a Knight of Rhodes, and Julius III named him a Knight of St. Peter, but the chain he wears for his 1545 portrait may have merely been jewelry. In his strictly-for-publication letters to patrons Aretino would often add a verbal portrait to Titian's painted one.

Titian was far from the only artist who portrayed Aretino. ″Probably no other celebrity of the cinquecento had his image reproduced so often and in so many media: paintings, frescoes, sculptures, prints, medals.... At various stages of his life Aretino was also portrayed by Sebastiano del Piombo, Alessandro Moretto, Francesco Salviati, Jacopo Tintoretto, and Giorgio Vasari. His portrait was engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi and Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio. His likeness was reproduced on medals by Leone Leoni, Francesco Segala, Alfonso Lombardi, and Alessandro Vittoria and his image was sculpted by Jacopo Sansovino and Danese Cattaneo.″[13]

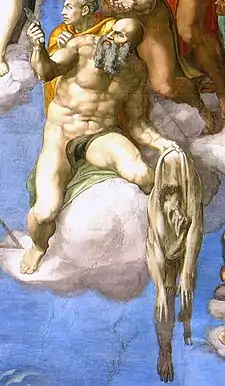

In November 1545, Aretino wrote an open letter to Michelangelo criticizing the nudity in The Last Judgment. His dialogues La Nanna, Aretino wrote, ″demonstrate the superiority of my reserve to your indiscretion, seeing that I, while handling themes lascivious and immodest, use language comely and decorous, speak in terms beyond reproach and inoffensive to chaste ears. You, on the contrary, presenting so awful a subject, exhibit saints and angels, these without earthly decency, and those without celestial honors…. Your art would be at home in some voluptuous bagnio, certainly not in the highest chapel in the world…. I do not write this out of any resentment for the things I begged of you. In truth, if you had sent me what you promised, you would only have been doing what you ought to have desired most eagerly to do in your own interest….″[14] John Addington Symonds writes, ″Aretino’s real object was to wheedle some priceless sketch or drawing out of the great master. This appears from a second letter written by him on the 20th of January 1538.″[15]

Symonds describes Michelangelo’s answer to Aretino’s November 1545 letter: ″Under the form of elaborate compliment it conceals the scorn he must have conceived for Aretino and his insolent advice. Yet he knew how dangerous the man could be, and felt obliged to humour him.″[16] In Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment, completed in 1541, he had painted Saint Bartholomew displaying his own flayed skin. ″[T]he sagging flayed skin … many scholars believe depicts Michelangelo’s own features. Interestingly, the face of Saint Bartholomew [who is holding the skin] is similar to the face of Pietro Aretino, one of Michelangelo’s chief persecutors.″[17]

Aretino is frequently mentioned in English works of the Elizabethan and later periods and differently appreciated, in comments ranging from 'It was one of the wittiest knaves that ever God made' of Nashe (The Unfortunate Traveller) to 'that notorious ribald of Arezzo' of Milton (Areopagitica).[18]

He is said to have died of suffocation from "laughing too much".[19]

The English traveller Sir John Reresby visited "the obscene profane poet" Aretino's grave in the Church of San Luca, Venice, in the mid-1650s. He relates that the following epitaph had been removed by the inquisitors: "Qui jace Aretin, poeta Tusco, qui dice mal d'ogni uno fuora di Dio; scusandosi dicendo, Io no'l cognosco." This he translates as "Here Aretin, the Tuscan poet, lies, who all the world abused but God, and why? he said he knew him not."[20]

However, the epitaph, in hendecasyllables a maiore, was a sarcastic one, attributed to Catholic Bishop Paolo Giovio, composed when Aretino was still alive:[21]

Qui giace l'Aretin, poeta tosco:

Di tutti disse mal fuorché di Cristo,

Scusandosi col dir: non lo conosco.

Legacy

In 2007, the composer Michael Nyman set some of Aretino's Sonetti lussuriosi to music under the title 8 Lust Songs. Once again, Aretino's texts proved controversial: at a 2008 performance at Cadogan Hall, London, the printed programs were withdrawn following allegations of obscenity.[22]

Works

Poetry

- Sonetti lussuriosi (1526). Erotically explicit sonnets written to accompany Marcantonio Raimondi's engravings of Giulio Romano's drawings of sexual positions in I Modi.

- Dubbi amorosi (1526). A series of questions and answers on erotic matters, expressed as poems in ottava rima and quatrains.

- Marfisa (1527-; publ. 1532, 1535)

- Angelica (publ. 1536)

- Orlandino (publ. 1540)

- Astolfeida (publ. ca. 1547)

Prose

- Lettere

- Ragionamenti (1534, 1536). A pair of Renaissance dialogues. In the Dialogue of Nanna and Antonia under a fig-tree in Rome (1534), the two women discuss the life options open to Nanna's daughter, Pippa, to become a nun, a wife or a whore. In the follow-up Dialogue in which Nanna teaches her daughter Pippa (1536), the relations between prostitutes and their clients are discussed. Translated by Raymond Rosenthal as Aretino's Dialogues (New York: Stein and Day, 1971).

Plays

- Farza

- La cortigiana (1525, 1534). Comedy in five acts, a parody of the then-unpublished Il cortegiano by Baldassare Castiglione. First performance possibly in carnival 1525. A revised version was published in Venice in 1534.

- Il marescalco (1533). Comedy in five acts. The play served as a source for Malipiero's opera of the same name (Treviso, 1969).

- La talanta (1542). Comedy in five acts.

- Lo ipocrito (1542). Comedy in five acts.

- Il filosofo (1546). Comedy in five acts.

- L'Orazia (1546). Tragedy in verse.

Notes

- "Aretino". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Aretino". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- James Cleugh (1965). The Divine Aretino, Pietro of Arezzo, 1492-1556: A Biography. A. Blond. p. 9.

- Oxford illustrated encyclopedia. Judge, Harry George; Toyne, Anthony. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. 1985–1993. p. 21. ISBN 0-19-869129-7. OCLC 11814265.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Innamorati, Giuliano (1962), "Aretino, Pietro", Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian), 4, Treccani

- Sheila Hale, Titian: His Life (HarperCollins, 2012), p. 241.

- Burckhardt, Jacob (1878). The Civilization Of The Renaissance in Italy. University of Toronto - Robarts Library: Vienna Phaidon Press. p. 86. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Spectator 203, March 27, 1711.

- Luba Freedman, Titian's Portraits Through Aretino's Lens. (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995), p. 36. However, in Apollo magazine (20 September 2019), Frick curator Xavier Salomon argues that a painting in Kunstmuseum Basel is the 1527 portrait of Aretino that Titian painted for the Marquis of Mantua, Frederico Gonzaga. https://www.apollo-magazine.com/an-important-work-by-titian-has-been-hiding-in-plain-sight/

- Sheila Hale, Titian: His Life (HarperCollins, 2012), p. 433; Luba Freedman, Titian's Portraits Through Aretino's Lens, p. 36 (Freedman refers to the painting as ″Pilate Presents Jesus Christ Before the People.″)

- Luba Freedman, Titian's Portraits Through Aretino's Lens, 1995), p. 36.

- At the Museo del Prado website, under ″Collection,″ the discussion of ″La Gloria″ states, ″On a lower level are two elderly bearded men identified as Pietro Aretino and Titian himself in profile.″

- Luba Freedman, Titian's Portraits Through Aretino's Lens, p. 35.

- John Addington Symonds, The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti (The Modern Library, Random House, 1927), pp. 334, 335.

- John Addington Symonds, The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti (The Modern Library, Random House, 1927), p. 332.

- John Addington Symonds, The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti (The Modern Library, Random House, 1927), p. 332.

- James A. Connor, The Last Judgment: Michelangelo and the Death of the Renaissance (Palgrave MacMillan, 2009), p. 140.

- The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6th edition, ed. Margaret Drabble (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 39

- Waterfield, Gordon, ed. (1966). First Footsteps in East Africa. New York: Praeger Publishers. p. 59 footnote.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Albert Ivatt, M. A., ed: The Memoir and Travels of Sir John Reresby, Bart. (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1904), p. 60.

- Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi, Scritti, Le Monnier, 1848, p. 188)

- "Classical Music News: The Classical Source News: Michael Nyman Festival Controversy: Classical Music News". Classicalsource.com. 9 June 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

References

- Bernadine Barnes, "Aretino, the Public, and the Censorship of Michelangelo's Last Judgment," in Suspended License: Censorship and the Visual Arts, ed. Elizabeth C. Childs (University of Washington Press, 1997), pp. 59–84[1]

- Bernadine Barnes, Michelangelo’s Last Judgment: The Renaissance Response (University of California Press, 1998) ISBN 0-520-20549-9, google books; pp. 74 et seq. discusses ″Aretino and the ′Public.′″

- Elise Boillet, "L'Aretin et les papes de son temps" in: Florence Alazard et Frank La Brasca (eds), La Papauté à la Renaissance (Paris, Editions Honoré Champion, 2007) (Travaux du Centre d'Études Supérieures de la Renaissance de Tours, 12), pp. 324–63

- Peter Brand, Charles Peter Brand and Lino Pertile, The Cambridge History of Italian Literature (Cambridge University Press, 1999) ISBN 978-0-521-66622-0

- Danny Chaplin, Pietro Aretino: The First Modern (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017) ISBN 978-1546393535

- Thomas Caldecot Chubb, Aretino: Scourge of Princes (Reynal & Hitchcock, 1940)

- James Cleugh, The Divine Aretino: A Biography (Stein and Day, 1966)

- Luba Freedman, Titian's Portraits Through Aretino's Lens (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995) ISBN 978-0-271-01339-8

- Robert Greene, The 48 Laws of Power (Viking Penguin, 1998) ISBN 0-14-028019-7

- Edward Hutton, Pietro Aretino: The Scourge of Princes (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1922)

- Mark A. Lamonica, Renaissance Porn Star: The Saga of Pietro Aretino, The World's Greatest Hustler (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012)

- Rictor Norton (ed.) My Dear Boy: Gay Love Letters through the Centuries (Leyland Publications, San Francisco, 1998)

- Joseph Satin, Pietro Aretino: The Sentient of Venice: A Novel (Press at California State University, Fresno, 2011)

Sources

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pietro Aretino. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pietro Aretino |

| Italian Wikisource has original text related to this article: |