Polaris Sales Agreement

The Polaris Sales Agreement was a treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom which began the UK Polaris programme. The agreement was signed on 6 April 1963. It formally arranged the terms and conditions under which the Polaris missile system was provided to the United Kingdom.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

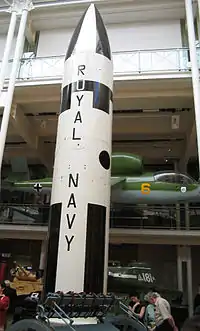

British Polaris missile on display at the Imperial War Museum in London | |

| Signed | 6 April 1963 |

| Location | Washington, DC |

| Effective | 6 April 1963 |

| Signatories | Dean Rusk (US) David Ormsby-Gore (UK) |

The United Kingdom had been planning to buy the air-launched Skybolt missile to extend the operational life of the British V bombers, but the United States decided to cancel the Skybolt program in 1962 as it no longer needed the missile. The crisis created by the cancellation prompted an emergency meeting between the President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, and the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Harold Macmillan, which resulted in the Nassau Agreement, under which the United States agreed to provide Polaris missiles to the United Kingdom instead.

The Polaris Sales Agreement provided for the implementation of the Nassau Agreement. The United States would supply the United Kingdom with Polaris missiles, launch tubes, and the fire control system. The United Kingdom would manufacture the warheads and submarines. In return, the US was given certain assurances by the United Kingdom regarding the use of the missile, but not a veto on the use of British nuclear weapons. The British Resolution-class Polaris ballistic missile submarines were built on time and under budget, and came to be seen as a credible deterrent that enhanced Britain's international status.

Along with the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement, the Polaris Sales Agreement became a pillar of the nuclear Special Relationship between Britain and the United States. The agreement was amended in 1982 to provide for the sale of the Trident missile system.

Background

During the early part of the Second World War, Britain had a nuclear weapons project, codenamed Tube Alloys.[1] In August 1943, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Winston Churchill and the President of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt, signed the Quebec Agreement, which merged Tube Alloys with the American Manhattan Project.[2] The British government trusted that the United States would continue to share nuclear technology, which it regarded as a joint discovery,[3] but the 1946 McMahon Act ended cooperation.[4] Fearing a resurgence of United States isolationism, and Britain losing its great power status, the British government restarted its own development effort,[5] now codenamed High Explosive Research.[6] The first British atomic bomb was tested in Operation Hurricane on 3 October 1952.[7][8] The subsequent British development of the hydrogen bomb, and a favourable international relations climate created by the Sputnik crisis, led to the McMahon Act being amended in 1958, and the restoration of the nuclear Special Relationship in the form of the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement (MDA), which allowed Britain to acquire nuclear weapons systems from the United States.

Britain's nuclear weapons armament was initially based on free-fall bombs delivered by the V bombers of the Royal Air Force (RAF), but the possibility of the manned bomber becoming obsolete by the late 1960s due to improvements in anti-aircraft defences was foreseen. In 1953, work began on a medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) called Blue Streak,[10] but by 1958, there were concerns about its vulnerability to a pre-emptive nuclear strike.[11] To extend the effectiveness and operational life of the V bombers, an air-launched, rocket-propelled standoff missile called Blue Steel was developed,[12] but it was anticipated that the air defences of the Soviet Union would improve to the extent that V bombers might still find it difficult to attack their targets.[13] A solution appeared to be the American Skybolt missile, which combined the range of Blue Streak with the mobile basing of the Blue Steel, and was small enough that two could be carried on an Avro Vulcan bomber.[14]

An institutional challenge to Skybolt came from the United States Navy, which was developing a submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), the UGM-27 Polaris. The US Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Arleigh Burke, kept the First Sea Lord, Lord Mountbatten, apprised of its development.[15] By moving the deterrent out to sea, Polaris offered the prospect of a deterrent that was invulnerable to a first strike, and reduced the risk of a nuclear strike on the British Isles.[16] The British Nuclear Deterrent Study Group (BNDSG) produced a study that argued that SLBM technology was as yet unproven, that Polaris would be expensive, and that given the time it would take to build the boats, it could not be deployed before the early 1970s.[17] The Cabinet Defence Committee therefore approved the acquisition of Skybolt in February 1960.[18] The Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, met with the President, Dwight D. Eisenhower, in March 1960, and secured permission to buy Skybolt. In return, the Americans could base the US Navy's Polaris ballistic missile submarines in the Holy Loch in Scotland.[19] The financial arrangement was particularly favourable to Britain, as the US was charging only the unit cost of Skybolt, absorbing all the research and development costs.[20] With this agreement in hand, the cancellation of Blue Streak was announced in the House of Commons on 13 April 1960.[14]

The subsequent American decision to cancel Skybolt created a political crisis in the UK, and an emergency meeting between Macmillan and President John F. Kennedy was called in Nassau, Bahamas.[21] Macmillan rejected the US offers of paying half the cost of developing Skybolt, and of supplying the AGM-28 Hound Dog missile instead.[22] This brought options down to Polaris, but the Americans would only supply it on condition that it be used as part of a proposed Multilateral Force (MLF). Kennedy ultimately relented, and agreed to supply Britain with Polaris missiles, while "the Prime Minister made it clear that except where Her Majesty's Government may decide that supreme national interests are at stake, these British forces will be used for the purposes of international defence of the Western Alliance in all circumstances."[23] A joint statement to this effect, the Nassau Agreement, was issued on 21 December 1962.[23]

Negotiations

%252C_Dr._Wernher_von_Braun%252C_at_McDonnell_Aircraft_Corporation_in_St._Louis%252C_Missouri.jpg.webp)

With the Nassau Agreement in hand, it remained to work out the details. Vice Admiral Michael Le Fanu had a meeting with the United States Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara, on 21 December 1962, the final day of the Nassau conference. He found McNamara eager to help, and enthusiastic about the idea of Polaris costing as little as possible. The first issue identified was how many Polaris boats should be built. While the Vulcans to carry Skybolt were already in service, the submarines to carry Polaris were not, and there was no provision in the defence budget for them.[24] Some naval officers feared that their construction would adversely impact the hunter-killer submarine programme.[25] The First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Caspar John, denounced the "millstone of Polaris hung around our necks" as "potential wreckers of the real navy".[26]

The number of missiles required was based on substituting for Skybolt. To achieve the same capability, the BNDSG calculated that this would require eight Polaris submarines, each of which would have 16 missiles, for a total of 128 missiles, with 128 one-megaton warheads.[27] It was subsequently decided to halve this, based on the decision that the ability to destroy twenty Soviet cities would have nearly as great a deterrent effect as the ability to destroy forty.[28] The Admiralty considered the possibility of hybrid submarines that could operate as hunter-killers while carrying eight Polaris missiles,[29] but McNamara noted that this would be inefficient, as twice as many submarines would need to be on station to maintain the deterrent, and cautioned that the effect of tinkering with the US Navy's 16-missile layout was unpredictable.[24] The Treasury costed a four-boat Polaris fleet at £314 million by 1972/73.[30] A Cabinet Defence Committee meeting on 23 January 1963 approved the plan for four boats, with Thorneycroft noting that four boats would be cheaper and faster to build.[31]

A mission led by Sir Solly Zuckerman, the Chief Scientific Adviser to the Ministry of Defence, left for the United States to discuss Polaris on 8 January 1963. It included the Vice Chief of the Naval Staff, Vice Admiral Sir Varyl Begg; the Deputy Secretary of the Admiralty, James Mackay; Rear Admiral Hugh Mackenzie; and physicist Sir Robert Cockburn and F. J. Doggett from the Ministry of Aviation. That the involvement of the Ministry of Aviation might be a complicating factor was foreseen, but it had experience with nuclear weapons development. Mackenzie had been the Flag Officer Submarines until 31 December 1962, when Le Fanu had appointed him the Chief Polaris Executive (CPE). As such, he was directly answerable to Le Fanu as Controller of the Navy. His CPE staff was divided between London and Foxhill, near Bath, Somerset, where Royal Navy had its ship design, logistics and weapons groups. It was intended as a counterpart to the United States Navy Special Projects Office (SPO), with whom it would have to deal.[32]

The principal finding of the Zuckerman mission was that the Americans had developed a new version of the Polaris missile, the A3. With a range extended of 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km), it had a new weapons bay housing three re-entry vehicles (REBs or Re-Entry Bodies in US Navy parlance) and a new 200-kilotonne-of-TNT (840 TJ) W58 warhead to penetrate improved Soviet anti-missile defences expected to become available around 1970. A decision was therefore required on whether to purchase the old A2 missile or the new A3. The Zuckerman mission came out in favour of the new A3 missile, although it was still under development and not expected to enter service until August 1964, as the deterrent would remain credible for much longer.[33] The decision was endorsed by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Carrington, in May 1963, and was officially made by Thorneycroft on 10 June 1963.[34]

The choice of the A3 created a problem for the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE) at Aldermaston, for the Skybolt warhead that had recently been tested in the Tendrac nuclear test at the Nevada Test Site in the United States would require a redesigned Re-Entry System (RES) in order to be fitted to a Polaris missile, at an estimated cost of between £30 million and £40 million. The alternative was to make a British copy of the W58. While the AWRE was familiar with the W47 warhead used in the A2, it knew nothing of the W58. A presidential determination was required to release information on the W58 under the MDA, but with this in hand, a mission led by John Challens, the Chief of Warhead Development at the AWRE, visited the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory from 22 to 24 January 1963, and was shown details of the W58.[33]

The Zuckerman mission found the SPO helpful and forthcoming, but there was one major shock. The British were expected to contribute to the research and development costs of the A3, backdated to 1 January 1963. These were expected to top $700 million by 1968.[35] Skybolt had been offered to the UK at unit cost, with the US absorbing the research and development costs,[20] but no such agreement had been reached at Nassau for Polaris. Thorneycroft baulked at the prospect of paying research and development costs, but McNamara pointed out that the United States Congress would not stand for an agreement that placed all the burden on the United States.[36] Macmillan instructed the British Ambassador to the United States, Sir David Ormsby-Gore, to inform Kennedy that Britain was not willing to commit to an open-ended sharing of research and development costs, but, as a compromise, would pay an additional five per cent for each missile. He asked that Kennedy be informed that a breakdown of the Nassau Agreement would likely cause the fall of his government.[37] Ormsby-Gore met with Kennedy that very day, and while Kennedy noted that the five per cent offer "was not the most generous offer he had ever heard of",[38] he accepted it. McNamara, certain that the United States was being ripped off, calculated the five percent on top of not just the missiles, but their fire control and navigation systems as well, adding around £2 million to the bill. On Ormsby-Gore's advice, this formulation was accepted.[38]

An American mission now visited the United Kingdom. This was led by Paul H. Nitze, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, and included Walt W. Rostow, the Director of Policy Planning at the State Department, and Admiral Ignatius J. Galantin, the head of the SPO. The Americans had ideas about how the programme should be organised. They foresaw the UK Polaris programme having project officers from both countries, with a Joint Steering Task Group that met regularly to provide advice. This was accepted, and would become part of the final agreement.[39] However, a follow-up British mission under Leslie Williams, the Director General Atomic Weapons at the Ministry of Aviation, whose members included Challens and Rear Admiral Frederick Dossor, was given a letter by the SPO with a list of subjects that were off limits. These included penetration aids, which were held to be outside the scope of the Nassau Agreement.[40]

One remaining obstacle in the path of the programme was how it would be integrated with the MLF. The British response to the MLF concept "ranged from unenthusiastic to hostile throughout the military establishment and in the two principal political parties".[41] Apart from anything else, it was estimated to cost as much as £100 million over ten years. Nonetheless, the Foreign Office argued that Britain must support the MLF.[41] The Nassau Agreement had invigorated the MLF effort in the United States. Kennedy appointed Livingston T. Merchant to negotiate the MLF with the European governments, which he did in February and March 1963.[42] While reaffirming support for those parts of the Nassau Agreement concerning the MLF, the British were successful in getting them omitted from the Polaris Sales Agreement.[43]

_1983.JPEG.webp)

The British team completed drafting the agreement in March 1963, and copies were circulated for discussion.[44] The contracts for their construction were announced that month. The Polaris boats would be the largest submarines built in Britain up to that time, and would be built by Vickers Armstrong Shipbuilders in Barrow-in-Furness and Cammell Laird in Birkenhead. For similar reasons to the US Navy, the Royal Navy decided to base the boats at Faslane, on the Gareloch, not far from the US Navy's base on the Holy Loch.[45] The drawback of the site was that it isolated the Polaris boats from the rest of the navy.[46] The Polaris Sales Agreement was signed in Washington, DC, on 6 April 1963 by Ormsby-Gore and Dean Rusk, the United States Secretary of State.[47]

Outcome

The two liaison officers were appointed in April; Captain Peter la Niece became the Royal Navy project officer in Washington, DC, while Captain Phil Rollings became the US Navy project officer in London. The Joint Steering Task Group held its first meeting in Washington on 26 June 1963.[48] The shipbuilding programme would prove to be a remarkable achievement, with the four Resolution-class submarines built on time and within the budget.[49] The first boat, HMS Resolution was launched in September 1966, and commenced its first deterrent patrol in June 1968.[50] The annual running costs of the Polaris boats came to around two per cent of the defence budget, and they came to be seen as a credible deterrent that enhanced Britain's international status.[49] Along with the more celebrated 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement, the Polaris Sales Agreement became a pillar of the nuclear Special Relationship between Britain and the United States.[51][52]

Trident

The Polaris Sales Agreement provided an established framework for negotiations over missiles and re-entry systems.[51] The legal agreement took the form of amending the Polaris Sales Agreement through an exchange of notes between the two governments so that "Polaris" in the original now also covered the purchase of Trident. There were also some amendments to the classified annexes of the Polaris Sales Agreement to delete the exclusion of penetrating aids.[53] Under the Polaris Sales Agreement, the United Kingdom paid a five per cent levy on the cost of equipment supplied in recognition of US research and development costs already incurred. For Trident, a payment of $116 million was substituted.[54] The United Kingdom procured the Trident system from America and fitted them to their own submarines, which had only 16 missile tubes like Polaris rather than the 24 in the American Ohio class. The first Vanguard-class submarine, HMS Vanguard, entered operational service in December 1994, by which time the Cold War had ended.[55]

Notes

- Gowing 1964, pp. 108–111.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 277.

- Goldberg 1964, p. 410.

- Gowing & Arnold 1974a, pp. 106–108.

- Gowing & Arnold 1974a, pp. 181–184.

- Cathcart 1995, pp. 23–24, 48, 57.

- Cathcart 1995, p. 253.

- Gowing & Arnold 1974b, pp. 493–495.

- Jones 2017, p. 37.

- Moore 2010, pp. 42–46.

- Wynn 1994, pp. 186–191.

- Wynn 1994, pp. 197–199.

- Moore 2010, pp. 47–48.

- Young 2002, pp. 67–68.

- Young 2002, p. 61.

- Jones 2017, pp. 178–182.

- Young 2002, p. 72.

- Moore 2010, pp. 64–68.

- Harrison 1982, p. 27.

- Jones 2017, pp. 372–373.

- Jones 2017, pp. 375–376.

- Moore 2010, p. 177.

- Jones 2017, pp. 406–407.

- Moore 2001, p. 170.

- Moore 2010, p. 188.

- Jones 2017, pp. 291–292.

- Jones 2017, pp. 295–297.

- Jones 2017, p. 347.

- Jones 2017, p. 409.

- Jones 2017, p. 410.

- Jones 2017, pp. 410–411.

- Jones 2017, pp. 413–415.

- Moore 2010, p. 231.

- Jones 2017, pp. 416–417.

- Jones 2017, pp. 417–418.

- Jones 2017, pp. 420–421.

- Jones 2017, p. 422.

- Jones 2017, pp. 418–419.

- Jones 2017, pp. 434–441.

- Moore 2010, p. 184.

- Kaplan, Landa & Drea 2006, pp. 405–407.

- Jones 2017, pp. 428–434.

- Jones 2017, p. 443.

- Moore 2010, p. 232.

- Moore 2001, p. 169.

- Jones 2017, p. 444.

- Priest 2005, p. 358.

- Stoddart 2012, p. 34.

- Ludlam 2008, p. 257.

- Stoddart 2008, p. 89.

- Hare 2008, p. 190.

- Stoddart 2014, pp. 154–155.

- "Exchange of Notes concerning the Acquisition by the UK of the Trident II Weapon System under the Polaris Sales Agreement" (PDF). Treaty Series No. 8. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. March 1983. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- Stoddart 2014, pp. 245–246.

References

- Cathcart, Brian (1995). Test of Greatness: Britain's Struggle for the Atom Bomb. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5225-7. OCLC 31241690.

- Goldberg, Alfred (July 1964). "The Atomic Origins of the British Nuclear Deterrent". International Affairs. 40 (3): 409–429. doi:10.2307/2610825. JSTOR 2610825.

- Gowing, Margaret (1964). Britain and Atomic Energy 1939–1945. London: Macmillan. OCLC 3195209.

- Gowing, Margaret; Arnold, Lorna (1974a). Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic Energy, 1945–1952, Volume 1, Policy Making. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-15781-8. OCLC 611555258.

- Gowing, Margaret; Arnold, Lorna (1974b). Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic Energy, 1945–1952, Volume 2, Policy and Execution. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-16695-7. OCLC 946341039.

- Hare, Tim (2008). "The MDA:A Practitioner's View". In Mackby, Jenifer; Cornish, Paul (eds.). US-UK Nuclear Cooperation After 50 Years. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies Press. pp. 189–199. ISBN 978-0-89206-530-1. OCLC 845346116.

- Harrison, Kevin (1982). "From Independence to Dependence: Blue Streak, Skybolt, Nassau and Polaris". The RUSI Journal. 127 (4): 25–31. doi:10.1080/03071848208523423. ISSN 0307-1847.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946 (PDF). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07186-7. OCLC 637004643. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Jones, Jeffrey (2017). Volume I: From the V-Bomber Era to the Arrival Of Polaris, 1945–1964. The Official History of the UK Strategic Nuclear Deterrent. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-67493-6.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S.; Landa, Ronald D.; Drea, Edward J. (2006). The McNamara Ascendancy 1961–1965 (PDF). History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, volume 5. Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- Ludlam, Steve (2008). "The Role of Nuclear Submarine Propulsion". In Mackby, Jenifer; Cornish, Paul (eds.). US-UK Nuclear Cooperation After 50 Years. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies Press. pp. 247–258. ISBN 978-0-89206-530-1. OCLC 845346116.

- Moore, Richard (2001). The Royal Navy and Nuclear Weapons. Naval History and Policy. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-5195-8. OCLC 59549380.

- Moore, Richard (2010). Nuclear Illusion, Nuclear Reality: Britain, the United States and Nuclear Weapons 1958–64. Nuclear Weapons and International Security since 1945. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-21775-1. OCLC 705646392.

- Navias, Martin S. (1991). British Weapons and Strategic Planning, 1955–1958. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-827754-5. OCLC 22506593.

- Priest, Andrew (September 2005). "In American Hands: Britain, the United States and the Polaris Nuclear Project 1962–1968". Contemporary British History. 19 (3): 353–376. doi:10.1080/13619460500100450.

- Stoddart, Kristan (2008). "The Special Nuclear Relationship and the 1980 Trident Decision". In Mackby, Jenifer; Cornish, Paul (eds.). US-UK Nuclear Cooperation After 50 Years. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies Press. pp. 89–100. ISBN 978-0-89206-530-1. OCLC 845346116.

- Stoddart, Kristan (2012). Losing an Empire and Finding a Role: Britain, the USA, NATO and Nuclear Weapons, 1964–70. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-33656-2. OCLC 951512907.

- Stoddart, Kristan (2014). Facing Down the Soviet Union: Britain, the USA, NATO and Nuclear Weapons, 1976–83. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-44031-0. OCLC 900698250.

- Wynn, Humphrey (1994). RAF Strategic Nuclear Deterrent Forces, Their Origins, Roles and Deployment, 1946–1969. A documentary history. London: The Stationery Office. ISBN 0-11-772833-0.

- Young, Ken (2002). "The Royal Navy's Polaris Lobby: 1955–62". Journal of Strategic Studies. 25 (3): 56–86. doi:10.1080/01402390412331302775. ISSN 0140-2390.

External links

- "Polaris Sales Agreement" (PDF). Treaty Series No. 59. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. August 1963. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "Exchange of Notes concerning the Acquisition by the UK of the Trident II Weapon System under the Polaris Sales Agreement" (PDF). Treaty Series No. 8. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. March 1983. Retrieved 6 November 2017.