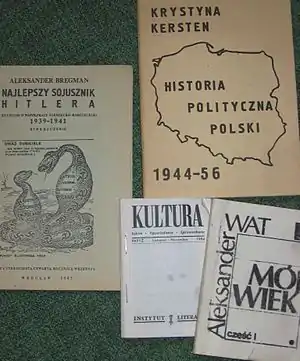

Polish underground press

Polish underground press, devoted to prohibited materials (sl. Polish: bibuła, lit. semitransparent blotting paper or, alternatively, Polish: drugi obieg, lit. second circulation), has a long history of combatting censorship of oppressive regimes in Poland. It existed throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, including under foreign occupation of the country, as well as during the totalitarian rule of the pro-Soviet government. Throughout the Eastern Bloc, bibuła published until the collapse of communism was known also as samizdat (see below).

Partitions of Poland

In the 19th century in partitioned Poland, many underground newspapers appeared; among the most prominent was the Robotnik, published in over 1,000 copies from 1894.

World War II

In the Second World War, in occupied Poland there were thousands of underground publications by the Polish Secret State and the Polish resistance. The Tajne Wojskowe Zakłady Wydawnicze (Secret Military Printing Works) was probably the largest underground publisher in the world.[1] The Home Army Biuletyn Informacyjny reached an estimated circulation of 47,000.[2]

Polish People's Republic

In the Polish People's Republic during the 1970s and 1980s, several books (sometimes as long as 500 pages) were printed in quantities often exceeding 5,000 copies. In 1980 and 1981, during the short legal existence of Solidarity trade union, actual newspapers were also published.

Most of the Polish underground press was organized in the 1970s by the Movement for Defense of Human and Civic Rights (ROPCiO) and Workers' Defence Committee (KOR). Over several years, alongside hundreds of small individual publishers, several large underground publishing houses were created, fueled by supplies smuggled from abroad or stolen from the backrooms of official publishing houses.

Throughout the communist era, Poland's Catholic Church and some Christian organizations and groups were allowed to publish a number of periodicals with a certain amount of freedom and a more or less clear anti-communist stand in various periods - but censored. The weekly Tygodnik Powszechny, half openly supporting KOR since 1976 and Solidarity since 1980, and monthly Więż were among the most popular.

A news-sheet Solidarność, printed in the Gdansk shipyard during the August 1980 strike, reached a print run of 30,000 copies daily.[3] The communist regime then allowed for two legal periodics to be published under the government control and cenzorship, yet with a significant margin of freedom: in January 1981, a regional weekly Jedność in Szczecin, and in May the nationwide weekly Tygodnik Solidarność with Tadeusz Mazowiecki as chief editor and circulation of 500,000. Both newspapers were dependent on the government grants of printing paper, what limited the number of copies. Semi-legal news bulletins were printed by Solidarity and other opposition groups in almost every town, on paper sent as aid by some Scandinavian and Western-European trade unions, without the regime's consent, but for the time being, rarely prosecuted. All that ended December 13, 1981, when gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski imposed a martial law and delegalized Solidarity.

The Polish underground press drew on experiences of Second World War veterans of Armia Krajowa and much attention was paid to conspiracy; however, after martial law in Poland and the government crackdown on Solidarity, the activities of underground publishing were significantly curtailed for several years. Nevertheless, with the communist government losing power in the second half of the 1980s, production of Polish underground printing (bibuła) dramatically increased, and many publications were distributed throughout the entire country. After the Revolutions of 1989 some of the underground publishers in Poland transformed into regular and legal publishing houses.

There were important differences of scale between Polish underground publishing and the samizdats of the Soviet Union, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and other countries in the Soviet Bloc. In the 1980s, at any given time there were around one hundred independent publishers in Poland who formed an exceptionally vibrant segment of the black market. Books were sold through underground distribution channels to paying customers, including subscribers. Among the few hundred regional periodicals with a usual hand-to-hand circulation of 2,000-5,000, the countrywide "Tygodnik Mazowsze" weekly reached an average circulation of 60,000 - 80,000 copies, while some issues topped 100,000. The estimated production of books and thick journals can be put close to one thousand per year and more than one million copies. Other products on this market included audio cassettes, videocassettes, posters, postcards, calendars, stamps and buttons.[4]

As an indication of how many Poles had access to underground publications in the martial-law decade, 3 of every 4 responders in a research in Kraków by the Niezależne Biuro Badania Opinii Społecznej NSZZ „Solidarność” (Solidarity's Independent Public Opinion Poll Bureau) in 1985 claimed to read it (26% "regularly", 47% "often". 22% chose "irregular and rare", with the remaining 5% declaring "never".[5] However, this range of influence had to be far more modest in smaller towns and countryside, where few underground grops were active.

References

- Stanisław Salmonowicz, (1994), Polskie Państwo Podziemne (Polish Underground State), Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, p. 187. ISBN 83-02-05500-X (in Polish)

- Straszewska, Maria (1967). "Biuletyn Informacyjny 1939-1944". RCIN.

- Colin Barker, The rise of Solidarnosc. International Socialism Quarterly, 17 October 2005.

- Archiwum Opozycji. Materiały dotyczące oporu wobec władzy komunistycznej (Collected materials of the anti-communist opposition in Poland). Ośrodek KARTA Center. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- Wierzbicki, Paweł (2012). "„Tygodnik Mazowsze" — cudowne dziecko drugiego obiegu (The wonderful child of Bibuła)" (PDF). RCIN Digital Repository.

External links

- Marek Kaminski - Book of Polish Political Prisoner and Underground Publisher makes various references to Polish underground publishing

- Foundation "Karta" founded to preserve documents related to Polish underground publications

- Kantorosinski, Zbigniew (1991). The Independent Press in Poland, 1976-1990. Washington, DC: Library of Congress.