Polychromasia

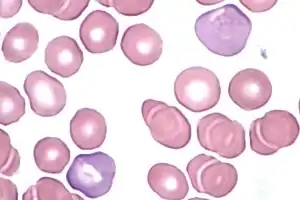

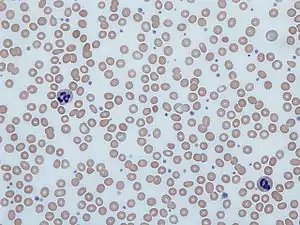

Polychromasia is a disorder where there is an abnormally high number of immature red blood cells found in the bloodstream as a result of being prematurely released from the bone marrow during blood formation. (poly- refers to many, and -chromasia means color.) These cells are often shades of grayish blue. Polychromasia is usually a sign of bone marrow stress as well as immature red blood cells. 3 types are recognized, with types (1) and (2) being referred to as 'young red blood cells' and type (3) as 'old red blood cells'. Giemsa stain is used to distinguish all three types in blood smears.[1] The young cells will generally stain gray or blue in the cytoplasm. These young red blood cells are commonly called reticulocytes. All polychromatophilic cells are reticulocytes, however, not all reticulocytes are polychromatophilic. In the old blood cells, the cytoplasm either stains a light orange or does not stain at all.

| Polychromasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Polychromatophilia |

| |

| Polychromatic red blood cells appear bluish-gray on the blood smear. | |

Causes

Red blood cells can be released prematurely by a number of mechanisms. Premature release of red blood cells is usually caused due to damage of the bone marrow due to underlying causes as well as in response to the stimulation of hormones in strong association with anemia. Erythropoetin, a hormone made by the kidneys, controls the production of the red blood cells as well as the rate at which they are released from the bone marrow. When these levels of erythropoetin rise, they signal the release of immature red blood cells into the bloodstream and is linked to anemia. Damaged bone marrow can also lead to polychromasia. The most common cause of bone marrow damage is penetration by cancer cells, either from the bone marrow itself or as a consequence of metastasis from another part of the body.

Association with anemia

Normocytic anemia is the most commonly seen type of anemia. This type of anemia is usually caused by underproduction of blood cells as well as hemolysis. Anemia can be caused by either overproduction or underproduction of red blood cells as well as the production of defective blood cells. Because there are more red blood cells needed in the body at that moment, they are released prematurely, leading to polychromasia.

Association with reticulocytosis

There is a slight correlation between polychromasia and reticulocytosis. It is much easier to test for polychromasia in blood cells than to perform special staining for reticulocytosis. If polychromasia is found in the blood cells, the reticulocyte count is taken to detect further disease or stress. If a low count of reticulocytes are found, it usually indicates bone marrow stress. If a high reticulocyte count is found, it is usually linked to hemolysis, but a Coombs test may be performed in this case to rule out immune-mediated hemolysis.[2] Polychromasia can also be seen in blood smears when there is a normal reticulocyte count. This can be caused by infiltration of the bone marrow due to tumors as well as fibrosis, or scarring, of the marrow.

Embryology

The formation of red blood cells is commonly known as hematopoiesis. Up to the first 60 days of life, the yolk sac is the main source of hematopoiesis. The liver is then used as the main hematopoietic organ of the embryo until near birth, where it is then taken over by the bone marrow.[3] Most red blood cells are released into the blood as reticulocytes. Polychromasia occurs when the immature reticulocytes of the bone marrow are released, resulting in a grayish blue color of the cells. This color is seen because of the ribosomes still left on the immature blood cells, which are not found on mature red blood cells. These cells still contain a nucleus as well due to the early release, which is not needed in mature blood cells because their only function is to carry oxygen in the blood. The life span of a typical red blood cell is acknowledged to be approximately 120 days and the time period of a reticulocyte found in the blood to be one day. The percentage of reticulocytes calculated to be in the blood at any given time indicates the rapidity of the red blood cell turnover in a healthy patient. The number of reticulocytes, however, reflects the amount of erythropoiesis that has occurred on any certain day.[4] The absolute number of reticulocytes is referred to as the reticulocyte index and is calculated by adjusting the reticulocyte percentage by the ratio of observed hematocrit to expected hematocrit to get the 'corrected' reticulocyte count.

Diagnosis

Polychromasia can be detected through the use of stains that will change the color of the red blood cells that are affected. Under certain conditions, these red blood cells are shown to have an affinity for basic stains, contrary to the usual acid stains used. Polychromatic cells usually stain dark blue or gray and are distinguishable from normal blood cells mostly by a slight change in color.

History

In 1890, research done by William Henry Howell indicated that certain red blood cells found both in fetal circulation and bone marrow (of a cat) had unusual granulation. These granules are also called Grawitz granules. In most instances he found that these granules were connected by a network of sorts. The cells that had this granulation were found in blood and tissues that had been freshly stained without undergoing fixation. Howell was the first to describe these blood cells as being of the prototype stippling, which meant granular degeneration of the red blood cells.[5] In 1893, Max Askanazy, who was studying the blood of an anemic patient, discovered granulation in the blood cells that were polychromatic. Later studies done by other scientists also showed the same results in other forms of anemia. This pattern of granulation was also seen in several types of toxic poisoning, especially lead poisoning. However, other research has shown that there has been stippling found in normal blood cells as well. Stippling is supposed to be one of the earliest symptoms of lead poisoning, although most scientists now regard it as a degenerative condition, along with polychromasia.

References

- Thomas, Lyell J. (1937). "On the Life Cycle of Contracaecum Spiculigerum". The Journal of Parasitology. 23 (4): 429–31. JSTOR 3272243.

- Camitta, Bruce M.; Slye, Rebecca Jean (2012). "Optimizing Use of the Complete Blood Count". Pediatria Polska. 87 (1): 72–77. doi:10.1016/S0031-3939(12)70597-8.

- Bleyl, Steven B., Philip R. Brauer, and Philippa H. Francis-West. "Development of Yolk Sac and Chorionic Cavity." Larsen's Human Embryology. By Gary C. Schoenwolf. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2009. 58. Print.

- Bessman JD (1990). "156 Reticulocytes". In Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW (eds.). Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations (3rd ed.). Butterworths. ISBN 0-409-90077-X. PMID 21250107. NBK264.

- Hawes, John B. (1909). "A Study of the Reticulated Red Blood Corpuscle by Means of Vital Staining Methods; Its Relation to Polychromatophilia and Stippling". Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 15: 493–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM190910071611501.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |