Anemia

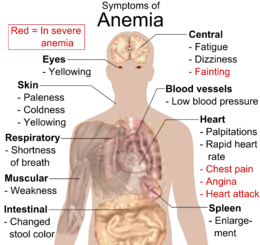

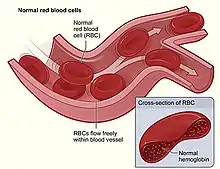

Anemia (also spelled anaemia) is a decrease in the total amount of red blood cells (RBCs) or hemoglobin in the blood,[3][4] or a lowered ability of the blood to carry oxygen.[5] When anemia comes on slowly, the symptoms are often vague and may include feeling tired, weakness, shortness of breath, and a poor ability to exercise.[1] When the anemia comes on quickly, symptoms may include confusion, feeling like one is going to pass out, loss of consciousness, and increased thirst.[1] Anemia must be significant before a person becomes noticeably pale.[1] Additional symptoms may occur depending on the underlying cause.[1] For people who require surgery, pre-operatve anemia can increase the risk of requiring a blood transfusion following surgery.[6]

| Anemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Anaemia |

| |

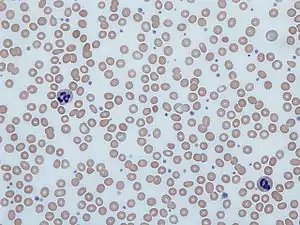

| Blood smear from a person with iron-deficiency anemia. Note the red cells are small and pale. | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Feeling tired, pale skin, weakness, shortness of breath, feeling like passing out[1] |

| Causes | Blood loss, decreased red blood cell production, increased red blood cell breakdown[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood hemoglobin measurement[1] |

| Frequency | 2.36 billion / 33% (2015)[2] |

Anemia can be caused by blood loss, decreased red blood cell production, and increased red blood cell breakdown.[1] Causes of blood loss include trauma and gastrointestinal bleeding.[1] Causes of decreased production include iron deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, thalassemia, and a number of neoplasms of the bone marrow.[1] Causes of increased breakdown include genetic conditions such as sickle cell anemia, infections such as malaria, and certain autoimmune diseases.[1] Anemia can also be classified based on the size of the red blood cells and amount of hemoglobin in each cell.[1] If the cells are small, it is called microcytic anemia; if they are large, it is called macrocytic anemia; and if they are normal sized, it is called normocytic anemia.[1] The diagnosis of anemia in men is based on a hemoglobin of less than 130 to 140 g/L (13 to 14 g/dL); in women, it is less than 120 to 130 g/L (12 to 13 g/dL).[1][7] Further testing is then required to determine the cause.[1][8]

Certain groups of individuals, such as pregnant women, benefit from the use of iron pills for prevention.[1][9] Dietary supplementation, without determining the specific cause, is not recommended.[1] The use of blood transfusions is typically based on a person's signs and symptoms.[1] In those without symptoms, they are not recommended unless hemoglobin levels are less than 60 to 80 g/L (6 to 8 g/dL).[1][10] These recommendations may also apply to some people with acute bleeding.[1] Erythropoiesis-stimulating medications are only recommended in those with severe anemia.[10]

Anemia is the most common blood disorder, affecting about a third of the global population.[1][2][11] Iron-deficiency anemia affects nearly 1 billion people.[12] In 2013, anemia due to iron deficiency resulted in about 183,000 deaths – down from 213,000 deaths in 1990.[13] It is more common in women than men,[12] during pregnancy, and in children and the elderly.[1] Anemia increases costs of medical care and lowers a person's productivity through a decreased ability to work.[7] The name is derived from Ancient Greek: ἀναιμία anaimia, meaning "lack of blood", from ἀν- an-, "not" and αἷμα haima, "blood".[14]

Anemia is one of the six WHO global nutrition targets for 2025 and diet-related global NCD targets for 2025, endorsed by World Health Assembly in 2012 and 2013. Efforts to reach global targets contributes reaching Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),[15] and Anemia being one of the targets in SDG 2.[16]

Signs and symptoms

Anemia goes undetected in many people and symptoms can be minor. The symptoms can be related to an underlying cause or the anemia itself. Most commonly, people with anemia report feelings of weakness or fatigue, and sometimes poor concentration. They may also report shortness of breath on exertion.

In very severe anemia, the body may compensate for the lack of oxygen-carrying capability of the blood by increasing cardiac output. The patient may have symptoms related to this, such as palpitations, angina (if pre-existing heart disease is present), intermittent claudication of the legs, and symptoms of heart failure. On examination, the signs exhibited may include pallor (pale skin, lining mucosa, conjunctiva and nail beds), but this is not a reliable sign. A blue coloration of the sclera may be noticed in some cases of iron-deficiency anemia.[18] There may be signs of specific causes of anemia, e.g., koilonychia (in iron deficiency), jaundice (when anemia results from abnormal break down of red blood cells – in hemolytic anemia), bone deformities (found in thalassemia major) or leg ulcers (seen in sickle-cell disease). In severe anemia, there may be signs of a hyperdynamic circulation: tachycardia (a fast heart rate), bounding pulse, flow murmurs, and cardiac ventricular hypertrophy (enlargement). There may be signs of heart failure. Pica, the consumption of non-food items such as ice, but also paper, wax, or grass, and even hair or dirt, may be a symptom of iron deficiency, although it occurs often in those who have normal levels of hemoglobin. Chronic anemia may result in behavioral disturbances in children as a direct result of impaired neurological development in infants, and reduced academic performance in children of school age. Restless legs syndrome is more common in people with iron-deficiency anemia than in the general population.[19]

Causes

The causes of anemia may be classified as impaired red blood cell (RBC) production, increased RBC destruction (hemolytic anemias), blood loss and fluid overload (hypervolemia). Several of these may interplay to cause anemia. The most common cause of anemia is blood loss, but this usually does not cause any lasting symptoms unless a relatively impaired RBC production develops, in turn most commonly by iron deficiency.[21]

Impaired production

- Disturbance of proliferation and differentiation of stem cells

- Pure red cell aplasia[22]

- Aplastic anemia[22] affects all kinds of blood cells. Fanconi anemia is a hereditary disorder or defect featuring aplastic anemia and various other abnormalities.

- Anemia of kidney failure[22] due to insufficient production of the hormone erythropoietin

- Anemia of endocrine disorders[23]

- Disturbance of proliferation and maturation of erythroblasts

- Pernicious anemia[22] is a form of megaloblastic anemia due to vitamin B12 deficiency dependent on impaired absorption of vitamin B12. Lack of dietary B12 causes non-pernicious megaloblastic anemia

- Anemia of folate deficiency,[22] as with vitamin B12, causes megaloblastic anemia

- Anemia of prematurity, by diminished erythropoietin response to declining hematocrit levels, combined with blood loss from laboratory testing, generally occurs in premature infants at two to six weeks of age.

- Iron deficiency anemia, resulting in deficient heme synthesis[22]

- Thalassemias, causing deficient globin synthesis[22]

- Congenital dyserythropoietic anemias, causing ineffective erythropoiesis

- Anemia of kidney failure[22] (also causing stem cell dysfunction)

- Other mechanisms of impaired RBC production

- Myelophthisic anemia[22] or myelophthisis is a severe type of anemia resulting from the replacement of bone marrow by other materials, such as malignant tumors, fibrosis, or granulomas.

- Myelodysplastic syndrome[22]

- anemia of chronic inflammation[22]

- Leukoerythroblastic anemia is caused by space-occupying lesions in the bone marrow that prevent normal production of blood cells.[24]

Increased destruction

Anemias of increased red blood cell destruction are generally classified as hemolytic anemias. These are generally featuring jaundice and elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels.

- Intrinsic (intracorpuscular) abnormalities[22] cause premature destruction. All of these, except paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, are hereditary genetic disorders.[25]

- Hereditary spherocytosis[22] is a hereditary defect that results in defects in the RBC cell membrane, causing the erythrocytes to be sequestered and destroyed by the spleen.

- Hereditary elliptocytosis[22] is another defect in membrane skeleton proteins.

- Abetalipoproteinemia,[22] causing defects in membrane lipids

- Enzyme deficiencies

- Pyruvate kinase and hexokinase deficiencies,[22] causing defect glycolysis

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and glutathione synthetase deficiency,[22] causing increased oxidative stress

- Hemoglobinopathies

- Sickle cell anemia[22]

- Hemoglobinopathies causing unstable hemoglobins[22]

- Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria[22]

- Extrinsic (extracorpuscular) abnormalities

- Antibody-mediated

- Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia is caused by autoimmune attack against red blood cells, primarily by IgG. It is the most common of the autoimmune hemolytic diseases.[26] It can be idiopathic, that is, without any known cause, drug-associated or secondary to another disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus, or a malignancy, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia.[27]

- Cold agglutinin hemolytic anemia is primarily mediated by IgM. It can be idiopathic[28] or result from an underlying condition.

- Rh disease,[22] one of the causes of hemolytic disease of the newborn

- Transfusion reaction to blood transfusions[22]

- Mechanical trauma to red blood cells

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemias, including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and disseminated intravascular coagulation[22]

- Infections, including malaria[22]

- Heart surgery

- Haemodialysis

- Antibody-mediated

Blood loss

- Anemia of prematurity, from frequent blood sampling for laboratory testing, combined with insufficient RBC production

- Trauma[22] or surgery, causing acute blood loss

- Gastrointestinal tract lesions,[22] causing either acute bleeds (e.g. variceal lesions, peptic ulcers) or chronic blood loss (e.g. angiodysplasia)

- Gynecologic disturbances,[22] also generally causing chronic blood loss

- From menstruation, mostly among young women or older women who have fibroids

- Many type of cancers, including colorectal cancer and cancer of the urinary bladder, may cause acute or chronic blood loss, especially at advanced stages

- Infection by intestinal nematodes feeding on blood, such as hookworms[29] and the whipworm Trichuris trichiura [30]

- Iatrogenic anemia, blood loss from repeated blood draws and medical procedures.[31][32]

The roots of the words anemia and ischemia both refer to the basic idea of "lack of blood", but anemia and ischemia are not the same thing in modern medical terminology. The word anemia used alone implies widespread effects from blood that either is too scarce (e.g., blood loss) or is dysfunctional in its oxygen-supplying ability (due to whatever type of hemoglobin or erythrocyte problem). In contrast, the word ischemia refers solely to the lack of blood (poor perfusion). Thus ischemia in a body part can cause localized anemic effects within those tissues.

Fluid overload

Fluid overload (hypervolemia) causes decreased hemoglobin concentration and apparent anemia:

- General causes of hypervolemia include excessive sodium or fluid intake, sodium or water retention and fluid shift into the intravascular space.[33]

- From the 6th week of pregnancy hormonal changes cause an increase in the mother's blood volume due to an increase in plasma.[34]

Intestinal inflammation

Certain gastrointestinal disorders can cause anemia. The mechanisms involved are multifactorial and not limited to malabsorption but mainly related to chronic intestinal inflammation, which causes dysregulation of hepcidin that leads to decreased access of iron to the circulation.[35][36][37]

- Helicobacter pylori infection.[38]

- Gluten-related disorders: untreated celiac disease[37][38] and non-celiac gluten sensitivity.[39] Anemia can be the only manifestation of celiac disease, in absence of gastrointestinal or any other symptoms.[40]

- Inflammatory bowel disease.[41][42]

Diagnosis

Definitions

There are a number of definitions of anemia; reviews provide comparison and contrast of them.[43] A strict but broad definition is an absolute decrease in red blood cell mass,[44] however, a broader definition is a lowered ability of the blood to carry oxygen.[5] An operational definition is a decrease in whole-blood hemoglobin concentration of more than 2 standard deviations below the mean of an age- and sex-matched reference range.[45]

It is difficult to directly measure RBC mass,[46] so the hematocrit (amount of RBCs) or the hemoglobin (Hb) in the blood are often used instead to indirectly estimate the value.[47] Hematocrit; however, is concentration dependent and is therefore not completely accurate. For example, during pregnancy a woman's RBC mass is normal but because of an increase in blood volume the hemoglobin and hematocrit are diluted and thus decreased. Another example would be bleeding where the RBC mass would decrease but the concentrations of hemoglobin and hematocrit initially remains normal until fluids shift from other areas of the body to the intravascular space.

The anemia is also classified by severity into mild (110 g/L to normal), moderate (80 g/L to 110 g/L), and severe anemia (less than 80 g/L) in adult males and adult non pregnant females.[48] Different values are used in pregnancy and children.[48]

Testing

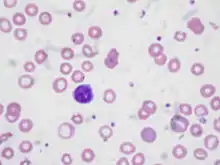

Anemia is typically diagnosed on a complete blood count. Apart from reporting the number of red blood cells and the hemoglobin level, the automatic counters also measure the size of the red blood cells by flow cytometry, which is an important tool in distinguishing between the causes of anemia. Examination of a stained blood smear using a microscope can also be helpful, and it is sometimes a necessity in regions of the world where automated analysis is less accessible.

In modern counters, four parameters (RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, MCV and RDW) are measured, allowing others (hematocrit, MCH and MCHC) to be calculated, and compared to values adjusted for age and sex. Some counters estimate hematocrit from direct measurements.

| Age or gender group | Hb threshold (g/dl) | Hb threshold (mmol/l) |

|---|---|---|

| Children (0.5–5.0 yrs) | 11.0 | 6.8 |

| Children (5–12 yrs) | 11.5 | 7.1 |

| Teens (12–15 yrs) | 12.0 | 7.4 |

| Women, non-pregnant (>15yrs) | 12.0 | 7.4 |

| Women, pregnant | 11.0 | 6.8 |

| Men (>15yrs) | 13.0 | 8.1 |

Reticulocyte counts, and the "kinetic" approach to anemia, have become more common than in the past in the large medical centers of the United States and some other wealthy nations, in part because some automatic counters now have the capacity to include reticulocyte counts. A reticulocyte count is a quantitative measure of the bone marrow's production of new red blood cells. The reticulocyte production index is a calculation of the ratio between the level of anemia and the extent to which the reticulocyte count has risen in response. If the degree of anemia is significant, even a "normal" reticulocyte count actually may reflect an inadequate response. If an automated count is not available, a reticulocyte count can be done manually following special staining of the blood film. In manual examination, activity of the bone marrow can also be gauged qualitatively by subtle changes in the numbers and the morphology of young RBCs by examination under a microscope. Newly formed RBCs are usually slightly larger than older RBCs and show polychromasia. Even where the source of blood loss is obvious, evaluation of erythropoiesis can help assess whether the bone marrow will be able to compensate for the loss, and at what rate. When the cause is not obvious, clinicians use other tests, such as: ESR, ferritin, serum iron, transferrin, RBC folate level, serum vitamin B12, hemoglobin electrophoresis, renal function tests (e.g. serum creatinine) although the tests will depend on the clinical hypothesis that is being investigated. When the diagnosis remains difficult, a bone marrow examination allows direct examination of the precursors to red cells, although is rarely used as is painful, invasive and is hence reserved for cases where severe pathology needs to be determined or excluded.

Red blood cell size

In the morphological approach, anemia is classified by the size of red blood cells; this is either done automatically or on microscopic examination of a peripheral blood smear. The size is reflected in the mean corpuscular volume (MCV). If the cells are smaller than normal (under 80 fl), the anemia is said to be microcytic; if they are normal size (80–100 fl), normocytic; and if they are larger than normal (over 100 fl), the anemia is classified as macrocytic. This scheme quickly exposes some of the most common causes of anemia; for instance, a microcytic anemia is often the result of iron deficiency. In clinical workup, the MCV will be one of the first pieces of information available, so even among clinicians who consider the "kinetic" approach more useful philosophically, morphology will remain an important element of classification and diagnosis. Limitations of MCV include cases where the underlying cause is due to a combination of factors – such as iron deficiency (a cause of microcytosis) and vitamin B12 deficiency (a cause of macrocytosis) where the net result can be normocytic cells.

Production vs. destruction or loss

The "kinetic" approach to anemia yields arguably the most clinically relevant classification of anemia. This classification depends on evaluation of several hematological parameters, particularly the blood reticulocyte (precursor of mature RBCs) count. This then yields the classification of defects by decreased RBC production versus increased RBC destruction or loss. Clinical signs of loss or destruction include abnormal peripheral blood smear with signs of hemolysis; elevated LDH suggesting cell destruction; or clinical signs of bleeding, such as guaiac-positive stool, radiographic findings, or frank bleeding. The following is a simplified schematic of this approach:

| Anemia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reticulocyte production index shows inadequate production response to anemia. | Reticulocyte production index shows appropriate response to anemia = ongoing hemolysis or blood loss without RBC production problem. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No clinical findings consistent with hemolysis or blood loss: pure disorder of production. | Clinical findings and abnormal MCV: hemolysis or loss and chronic disorder of production*. | Clinical findings and normal MCV= acute hemolysis or loss without adequate time for bone marrow production to compensate**. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Macrocytic anemia (MCV>100) | Normocytic anemia (80<MCV<100) | Microcytic anemia (MCV<80) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

* For instance, sickle cell anemia with superimposed iron deficiency; chronic gastric bleeding with B12 and folate deficiency; and other instances of anemia with more than one cause.

** Confirm by repeating reticulocyte count: ongoing combination of low reticulocyte production index, normal MCV and hemolysis or loss may be seen in bone marrow failure or anemia of chronic disease, with superimposed or related hemolysis or blood loss.

Here is a schematic representation of how to consider anemia with MCV as the starting point:

| Anemia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Macrocytic anemia (MCV>100) | Normocytic anemia (MCV 80–100) | Microcytic anemia (MCV<80) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| High reticulocyte count | Low reticulocyte count | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other characteristics visible on the peripheral smear may provide valuable clues about a more specific diagnosis; for example, abnormal white blood cells may point to a cause in the bone marrow.

Microcytic

Microcytic anemia is primarily a result of hemoglobin synthesis failure/insufficiency, which could be caused by several etiologies:

- Heme synthesis defect

- Iron deficiency anemia (microcytosis is not always present)

- Anemia of chronic disease (more commonly presenting as normocytic anemia)

- Globin synthesis defect

- Alpha-, and beta-thalassemia

- HbE syndrome

- HbC syndrome

- Various other unstable hemoglobin diseases

- Sideroblastic defect

- Hereditary sideroblastic anemia

- Acquired sideroblastic anemia, including lead toxicity[50]

- Reversible sideroblastic anemia

Iron deficiency anemia is the most common type of anemia overall and it has many causes. RBCs often appear hypochromic (paler than usual) and microcytic (smaller than usual) when viewed with a microscope.

- Iron deficiency anemia is due to insufficient dietary intake or absorption of iron to meet the body's needs. Infants, toddlers, and pregnant women have higher than average needs. Increased iron intake is also needed to offset blood losses due to digestive tract issues, frequent blood donations, or heavy menstrual periods.[51] Iron is an essential part of hemoglobin, and low iron levels result in decreased incorporation of hemoglobin into red blood cells. In the United States, 12% of all women of childbearing age have iron deficiency, compared with only 2% of adult men. The incidence is as high as 20% among African American and Mexican American women.[52] Studies have shown iron deficiency without anemia causes poor school performance and lower IQ in teenage girls, although this may be due to socioeconomic factors.[53][54] Iron deficiency is the most prevalent deficiency state on a worldwide basis. It is sometimes the cause of abnormal fissuring of the angular (corner) sections of the lips (angular stomatitis).

- In the United States, the most common cause of iron deficiency is bleeding or blood loss, usually from the gastrointestinal tract. Fecal occult blood testing, upper endoscopy and lower endoscopy should be performed to identify bleeding lesions. In older men and women, the chances are higher that bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract could be due to colon polyps or colorectal cancer.

- Worldwide, the most common cause of iron deficiency anemia is parasitic infestation (hookworms, amebiasis, schistosomiasis and whipworms).[55]

The Mentzer index (mean cell volume divided by the RBC count) predicts whether microcytic anemia may be due to iron deficiency or thalassemia, although it requires confirmation.[56]

Macrocytic

- Megaloblastic anemia, the most common cause of macrocytic anemia, is due to a deficiency of either vitamin B12, folic acid, or both. Deficiency in folate or vitamin B12 can be due either to inadequate intake or insufficient absorption. Folate deficiency normally does not produce neurological symptoms, while B12 deficiency does.

- Pernicious anemia is caused by a lack of intrinsic factor, which is required to absorb vitamin B12 from food. A lack of intrinsic factor may arise from an autoimmune condition targeting the parietal cells (atrophic gastritis) that produce intrinsic factor or against intrinsic factor itself. These lead to poor absorption of vitamin B12.

- Macrocytic anemia can also be caused by removal of the functional portion of the stomach, such as during gastric bypass surgery, leading to reduced vitamin B12/folate absorption. Therefore, one must always be aware of anemia following this procedure.

- Hypothyroidism

- Alcoholism commonly causes a macrocytosis, although not specifically anemia. Other types of liver disease can also cause macrocytosis.

- Drugs such as methotrexate, zidovudine, and other substances may inhibit DNA replication such as heavy metals

Macrocytic anemia can be further divided into "megaloblastic anemia" or "nonmegaloblastic macrocytic anemia". The cause of megaloblastic anemia is primarily a failure of DNA synthesis with preserved RNA synthesis, which results in restricted cell division of the progenitor cells. The megaloblastic anemias often present with neutrophil hypersegmentation (six to 10 lobes). The nonmegaloblastic macrocytic anemias have different etiologies (i.e. unimpaired DNA globin synthesis,) which occur, for example, in alcoholism. In addition to the nonspecific symptoms of anemia, specific features of vitamin B12 deficiency include peripheral neuropathy and subacute combined degeneration of the cord with resulting balance difficulties from posterior column spinal cord pathology.[57] Other features may include a smooth, red tongue and glossitis. The treatment for vitamin B12-deficient anemia was first devised by William Murphy, who bled dogs to make them anemic, and then fed them various substances to see what (if anything) would make them healthy again. He discovered that ingesting large amounts of liver seemed to cure the disease. George Minot and George Whipple then set about to isolate the curative substance chemically and ultimately were able to isolate the vitamin B12 from the liver. All three shared the 1934 Nobel Prize in Medicine.[58]

Normocytic

Normocytic anemia occurs when the overall hemoglobin levels are decreased, but the red blood cell size (mean corpuscular volume) remains normal. Causes include:

- Acute blood loss

- Anemia of chronic disease

- Aplastic anemia (bone marrow failure)

- Hemolytic anemia

Dimorphic

A dimorphic appearance on a peripheral blood smear occurs when there are two simultaneous populations of red blood cells, typically of different size and hemoglobin content (this last feature affecting the color of the red blood cell on a stained peripheral blood smear). For example, a person recently transfused for iron deficiency would have small, pale, iron deficient red blood cells (RBCs) and the donor RBCs of normal size and color. Similarly, a person transfused for severe folate or vitamin B12 deficiency would have two cell populations, but, in this case, the patient's RBCs would be larger and paler than the donor's RBCs. A person with sideroblastic anemia (a defect in heme synthesis, commonly caused by alcoholism, but also drugs/toxins, nutritional deficiencies, a few acquired and rare congenital diseases) can have a dimorphic smear from the sideroblastic anemia alone. Evidence for multiple causes appears with an elevated RBC distribution width (RDW), indicating a wider-than-normal range of red cell sizes, also seen in common nutritional anemia.

Heinz body anemia

Heinz bodies form in the cytoplasm of RBCs and appear as small dark dots under the microscope. In animals, Heinz body anemia has many causes. It may be drug-induced, for example in cats and dogs by acetaminophen (paracetamol),[59] or may be caused by eating various plants or other substances:

Hyperanemia

Hyperanemia is a severe form of anemia, in which the hematocrit is below 10%.[62]

Refractory anemia

Refractory anemia, an anemia which does not respond to treatment,[63] is often seen secondary to myelodysplastic syndromes.[64] Iron deficiency anemia may also be refractory as a manifestation of gastrointestinal problems which disrupt iron absorption or cause occult bleeding. [65]

Transfusion dependent

Transfusion dependent anemia is a form of anemia where ongoing blood transfusion are required.[66] Most people with myelodysplastic syndrome develop this state at some point in time.[67] Beta thalassemia may also result in transfusion dependence.[68][69] Concerns from repeated blood transfusions include iron overload.[67] This iron overload may require chelation therapy.[70]

Treatment

Treatment for anemia depends on cause and severity. Vitamin supplements given orally (folic acid or vitamin B12) or intramuscularly (vitamin B12) will replace specific deficiencies.

Oral iron

Nutritional iron deficiency is common in developing nations. An estimated two-thirds of children and of women of childbearing age in most developing nations are estimated to have iron deficiency without anemia; one-third of them have iron deficiency with anemia.[71] Iron deficiency due to inadequate dietary iron intake is rare in men and postmenopausal women. The diagnosis of iron deficiency mandates a search for potential sources of blood loss, such as gastrointestinal bleeding from ulcers or colon cancer.

Mild to moderate iron-deficiency anemia is treated by oral iron supplementation with ferrous sulfate, ferrous fumarate, or ferrous gluconate. Daily iron supplements have been shown to be effective in reducing anemia in women of childbearing age.[72] When taking iron supplements, stomach upset or darkening of the feces are commonly experienced. The stomach upset can be alleviated by taking the iron with food; however, this decreases the amount of iron absorbed. Vitamin C aids in the body's ability to absorb iron, so taking oral iron supplements with orange juice is of benefit.[73]

In the anemia of chronic kidney disease, recombinant erythropoietin or epoetin alfa is recommended to stimulate RBC production, and if iron deficiency and inflammation are also present, concurrent parenteral iron is also recommended.[74]

Injectable iron

In cases where oral iron has either proven ineffective, would be too slow (for example, pre-operatively) or where absorption is impeded (for example in cases of inflammation), parenteral iron preparations can be used. Parenteral iron can improve iron stores rapidly and is also effective for treating people with postpartum haemorrhage, inflammatory bowel disease, and chronic heart failure.[6] The body can absorb up to 6 mg iron daily from the gastrointestinal tract. In many cases the patient has a deficit of over 1,000 mg of iron which would require several months to replace. This can be given concurrently with erythropoietin to ensure sufficient iron for increased rates of erythropoiesis.[75]

Blood transfusions

Blood transfusions in those without symptoms is not recommended until the hemoglobin is below 60 to 80 g/L (6 to 8 g/dL).[1] In those with coronary artery disease who are not actively bleeding transfusions are only recommended when the hemoglobin is below 70 to 80g/L (7 to 8 g/dL).[10] Transfusing earlier does not improve survival.[76] Transfusions otherwise should only be undertaken in cases of cardiovascular instability.[77]

A 2012 review concluded that when considering blood transfusions for anaemia in people with advanced cancer who have fatigue and breathlessness (not related to cancer treatment or haemorrhage), consideration should be given to whether there are alternative strategies can be tried before a blood transfusion.[78]

Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents

The objective for the administration of an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) is to maintain hemoglobin at the lowest level that both minimizes transfusions and meets the individual person's needs.[79] They should not be used for mild or moderate anemia.[76] They are not recommended in people with chronic kidney disease unless hemoglobin levels are less than 10 g/dL or they have symptoms of anemia. Their use should be along with parenteral iron.[79][80] The 2020 Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group review of Erythropoietin plus iron versus control treatment including placebo or iron for preoperative anaemic adults undergoing non‐cardiac surgery [81] demonstrated that patients were much less likely to require red cell transfusion and in those transfused, the volumes were unchanged (mean difference -0.09, 95% CI -0.23 to 0.05). Pre-op Hb concentration was increased in those receiving ‘high dose’ EPO, but not ‘low dose’.

Hyperbaric oxygen

Treatment of exceptional blood loss (anemia) is recognized as an indication for hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) by the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society.[82][83] The use of HBO is indicated when oxygen delivery to tissue is not sufficient in patients who cannot be given blood transfusions for medical or religious reasons. HBO may be used for medical reasons when threat of blood product incompatibility or concern for transmissible disease are factors.[82] The beliefs of some religions (ex: Jehovah's Witnesses) may require they use the HBO method.[82] A 2005 review of the use of HBO in severe anemia found all publications reported positive results.[84]

Pre-operative anemia

An estimated 30% of adults who require non-cardiac surgery have anemia.[85] In order to determine an appropriate pre-operative treatment, it is suggested that the cause of anemia be first determined.[86] There is moderate level medical evidence that supports a combination of iron supplementation and erythropoietin treatment to help reduce the requirement for red blood cell transfusions after surgery in those who have pre-operative anemia.[85]

Epidemiology

A moderate degree of iron-deficiency anemia affected approximately 610 million people worldwide or 8.8% of the population.[12] It is slightly more common in females (9.9%) than males (7.8%).[12] Mild iron deficiency anemia affects another 375 million.[12]

History

Signs of severe anemia in human bones from 4000 years ago have been uncovered in Thailand.[87]

References

- Janz TG, Johnson RL, Rubenstein SD (November 2013). "Anemia in the emergency department: evaluation and treatment". Emergency Medicine Practice. 15 (11): 1–15, quiz 15–16. PMID 24716235. Archived from the original on 2016-10-18.

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- "What Is Anemia? – NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-01-20. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- Stedman's medical Dictionary (28th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006. p. Anemia. ISBN 978-0-7817-3390-8.

- Rodak BF (2007). Hematology : clinical principles and applications (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 220. ISBN 978-1-4160-3006-5. Archived from the original on 2016-04-25.

- Ng, Oliver; Keeler, Barrie D.; Mishra, Amitabh; Simpson, J. A.; Neal, Keith; Al-Hassi, Hafid Omar; Brookes, Matthew J.; Acheson, Austin G. (December 2019). "Iron therapy for preoperative anaemia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD011588. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011588.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6899074. PMID 31811820.

- Smith RE (March 2010). "The clinical and economic burden of anemia". The American Journal of Managed Care. 16 Suppl Issues: S59–66. PMID 20297873.

- Rhodes, Carl E.; Varacallo, Matthew (2019-03-04). "Physiology, Oxygen Transport". NCBI Bookshelf. PMID 30855920. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A, Gaffey MF, Walker N, Horton S, Webb P, Lartey A, Black RE (August 2013). "Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost?". Lancet. 382 (9890): 452–477. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60996-4. PMID 23746776. S2CID 11748341.

- Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Fitterman N, Starkey M, Shekelle P (December 2013). "Treatment of anemia in patients with heart disease: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (11): 770–779. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-11-201312030-00009. PMID 24297193.

- Peyrin-Biroulet, Laurent; Williet, Nicolas; Cacoub, Patrice (2015-12-01). "Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency across indications: a systematic review". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 102 (6): 1585–1594. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.103366. ISSN 0002-9165.

- Vos T, et al. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–2196. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- "anaemia". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- "WHO | Interventions by global target". www.who.int. World Health Organization.

- "The case for action on anemia".

- eMedicineHealth > anemia article Archived 2009-04-17 at the Wayback Machine Author: Saimak T. Nabili, MD, MPH. Editor: Melissa Conrad Stöppler, MD. Last Editorial Review: 12/9/2008. Retrieved on 4 April 2009

- Weksler, Babette (2017). Wintrobe's Atlas of Clinical Hematology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. PT105. ISBN 9781451154542.

- Allen, RP; Auerbach, S; Bahrain, H; Auerbach, M; Earley, CJ (April 2013). "The Prevalence and Impact of Restless Legs Syndrome on Patients with Iron Deficiency Anemia". Am J Hematol. 88 (4): 261–264. doi:10.1002/ajh.23397. PMID 23494945. S2CID 35587006.

- "Red Blood Cells". US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2017-01-01.

- "What Causes Anemia?". National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.

- Table 12-1 in: Mitchell RS, Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- Gregg, XT; Prchal, JT (2007). "Anemia of Endocrine Disorders". Williams Hermatology. McGraw-Hill.

- "the definition of leukoerythroblastosis". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- Mitchell RS, Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- Cotran RS, Kumar V, Fausto N, Robbins SL, Abbas AK (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. p. 637. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- "Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (AIHA)" By J.L. Jenkins. The Regional Cancer Center. 2001 Archived October 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Berentsen S, Beiske K, Tjønnfjord GE (October 2007). "Primary chronic cold agglutinin disease: an update on pathogenesis, clinical features and therapy". Hematology. 12 (5): 361–370. doi:10.1080/10245330701445392. PMC 2409172. PMID 17891600.

- Brooker S, Hotez PJ, Bundy DA (September 2008). "Hookworm-related anaemia among pregnant women: a systematic review". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (9): e291. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000291. PMC 2553481. PMID 18820740.

- Gyorkos TW, Gilbert NL, Larocque R, Casapía M (April 2011). "Trichuris and hookworm infections associated with anaemia during pregnancy". Tropical Medicine & International Health. 16 (4): 531–537. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02727.x. PMID 21281406. S2CID 205391965.

- Whitehead, Nedra S.; Williams, Laurina O.; Meleth, Sreelatha; Kennedy, Sara M.; Ubaka-Blackmoore, Nneka; Geaghan, Sharon M.; Nichols, James H.; Carroll, Patrick; McEvoy, Michael T.; Gayken, Julie; Ernst, Dennis J.; Litwin, Christine; Epner, Paul; Taylor, Jennifer; Graber, Mark L. (2019). "Interventions to prevent iatrogenic anemia: a Laboratory Medicine Best Practices systematic review". Critical Care. 23 (1): 278. doi:10.1186/s13054-019-2511-9. ISSN 1364-8535. PMC 6688222. PMID 31399052.

- Martin, Niels D.; Scantling, Dane (2015). "Hospital-Acquired Anemia". Journal of Infusion Nursing. 38 (5): 330–338. doi:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000121. ISSN 1533-1458. PMID 26339939. S2CID 30859103.

- "Fluid imbalances". Portable Fluids and Electrolytes (Portable Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-58255-678-9.

- "ISBT: 8. Obstetric anaemia". www.isbtweb.org. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- Verma S, Cherayil BJ (February 2017). "Iron and inflammation - the gut reaction". Metallomics (Review). 9 (2): 101–111. doi:10.1039/c6mt00282j. PMC 5321802. PMID 28067386.

- Guagnozzi D, Lucendo AJ (April 2014). "Anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: a neglected issue with relevant effects". World Journal of Gastroenterology (Review). 20 (13): 3542–3551. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i13.3542. PMC 3974521. PMID 24707137.

- Leffler DA, Green PH, Fasano A (October 2015). "Extraintestinal manifestations of coeliac disease". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology (Review). 12 (10): 561–571. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.131. PMID 26260366. S2CID 15561525. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12.

Malabsorption of nutrients is not the only cause of anaemia in coeliac disease, the chronic inflammatory process in the intestine contributes as well.

- Stein J, Connor S, Virgin G, Ong DE, Pereyra L (September 2016). "Anemia and iron deficiency in gastrointestinal and liver conditions". World Journal of Gastroenterology (Review). 22 (35): 7908–7925. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i35.7908. PMC 5028806. PMID 27672287.

- Catassi C, Bai JC, Bonaz B, Bouma G, Calabrò A, Carroccio A, Castillejo G, Ciacci C, Cristofori F, Dolinsek J, Francavilla R, Elli L, Green P, Holtmeier W, Koehler P, Koletzko S, Meinhold C, Sanders D, Schumann M, Schuppan D, Ullrich R, Vécsei A, Volta U, Zevallos V, Sapone A, Fasano A (September 2013). "Non-Celiac Gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders". Nutrients (Review). 5 (10): 3839–3853. doi:10.3390/nu5103839. PMC 3820047. PMID 24077239.

- James, Stephen P. (April 2005). "National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement on Celiac Disease, June 28-30, 2004". Gastroenterology (Review). 128 (4 Suppl 1): S1–9. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.007. PMID 15825115.

- Lomer MC (August 2011). "Dietary and nutritional considerations for inflammatory bowel disease". The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society (Review). 70 (3): 329–335. doi:10.1017/S0029665111000097. PMID 21450124.

- Gerasimidis K, McGrogan P, Edwards CA (August 2011). "The aetiology and impact of malnutrition in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease". Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics (Review). 24 (4): 313–326. doi:10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01171.x. PMID 21564345.

- Beutler E, Waalen J (March 2006). "The definition of anemia: what is the lower limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration?". Blood. 107 (5): 1747–1750. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-07-3046. PMC 1895695. PMID 16189263.

- Maakaron, Joseph (30 September 2016). "Anemia: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Etiology". Emedicine. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Pomeranz AJ, Sabnis S, Busey S, Kliegman RM (2016). Pediatric Decision-Making Strategies (2nd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-29854-4.

- Polin RA, Abman SH, Rowitch D, Benitz WE (2016). Fetal and Neonatal Physiology (5 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1085. ISBN 978-0-323-35232-1. Archived from the original on 2016-10-31.

- Uthman E (2009). Understanding Anemia. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-60473-701-1. Archived from the original on 2016-10-31.

- "Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-30.

- World Health Organization (2008). Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005 (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-159665-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- Caito S, Almeida Lopes AC, Paoliello MM, Aschner M (2017). "Chapter 16. Toxicology of Lead and Its Damage to Mammalian Organs". In Astrid S, Helmut S, Sigel RK (eds.). Lead: Its Effects on Environment and Health. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 17. de Gruyter. pp. 501–534. doi:10.1515/9783110434330-016. ISBN 9783110434330. PMID 28731309.

- Recommendations to Prevent and Control Iron Deficiency in the United States Archived 2007-04-20 at the Wayback Machine MMWR 1998;47 (No. RR-3) p. 5

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (October 11, 2002). "Iron Deficiency – United States, 1999–2000". MMWR. 51 (40): 897–899. PMID 12418542. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Halterman JS, Kaczorowski JM, Aligne CA, Auinger P, Szilagyi PG (June 2001). "Iron deficiency and cognitive achievement among school-aged children and adolescents in the United States". Pediatrics. 107 (6): 1381–1386. doi:10.1542/peds.107.6.1381. PMID 11389261. S2CID 33404386.

- Grantham-McGregor S, Ani C (February 2001). "A review of studies on the effect of iron deficiency on cognitive development in children". The Journal of Nutrition. 131 (2S–2): 649S–666S, discussion 666S–668S. doi:10.1093/jn/131.2.649S. PMID 11160596.

- "Iron Deficiency Anaemia: Assessment, Prevention, and Control: A guide for programme managers" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- Mentzer WC (April 1973). "Differentiation of iron deficiency from thalassaemia trait". Lancet. 1 (7808): 882. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91446-3. PMID 4123424.

- eMedicine – Vitamin B-12 Associated Neurological Diseases : Article by Niranjan N Singh, MD, DM, DNB Archived 2007-03-15 at the Wayback Machine July 18, 2006

- "Physiology or Medicine 1934 – Presentation Speech". Nobelprize.org. 1934-12-10. Archived from the original on 28 August 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- Harvey JW (2012). Veterinary hematology: a diagnostic guide and color atlas. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-4377-0173-9.

- Hovda L, Brutlag A, Poppenga RH, Peterson K, eds. (2016). "Chapter 69: Onions and garlic". Blackwell's Five-Minute Veterinary Consult Clinical Companion: Small Animal Toxicology (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 515–520. ISBN 978-1-119-03652-4.

- Peek SF (2014). "Chapter 117: Hemolytic disorders". In Sprayberry KA, Robinson NE (eds.). Robinson's Current Therapy in Equine Medicine (7th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 492–496. ISBN 978-0-323-24216-5.

- Wallerstein RO (April 1987). "Laboratory evaluation of anemia". The Western Journal of Medicine. 146 (4): 443–451. PMC 1307333. PMID 3577135.

- "MedTerms Definition: Refractory Anemia". Medterms.com. 2011-04-27. Archived from the original on 2011-12-08. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- "Good Source for later". Atlasgeneticsoncology.org. Archived from the original on 2011-11-03. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- Mody RJ, Brown PI, Wechsler DS (February 2003). "Refractory iron deficiency anemia as the primary clinical manifestation of celiac disease". Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 25 (2): 169–172. doi:10.1097/00043426-200302000-00018. PMID 12571473. S2CID 38832868.

- Gale RP, Barosi G, Barbui T, Cervantes F, Dohner K, Dupriez B, et al. (January 2011). "What are RBC-transfusion-dependence and -independence?". Leukemia Research. 35 (1): 8–11. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2010.07.015. PMID 20692036.

- Melchert M, List AF (2007). "Management of RBC-transfusion dependence". Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2007: 398–404. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.398. PMID 18024657.

- Hillyer CD, Silberstein LE, Ness PM, Anderson KC, Roback JD (2006). Blood Banking and Transfusion Medicine: Basic Principles and Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 534. ISBN 9780702036255.

- Mandel J, Taichman D (2006). Pulmonary Vascular Disease. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 170. ISBN 978-1416022466.

- Ferri FF (2015). BOPOD – Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2016. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1131.e2. ISBN 978-0323378222.

- West CE (November 1996). "Strategies to control nutritional anemia". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 64 (5): 789–790. doi:10.1093/ajcn/64.5.789. PMID 8901803.

- Low, MS; Speedy, J; Styles, CE; De-Regil, LM; Pasricha, SR (18 April 2016). "Daily iron supplementation for improving anaemia, iron status and health in menstruating women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD009747. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009747.pub2. PMID 27087396.

- Sezer S, Ozdemir FN, Yakupoglu U, Arat Z, Turan M, Haberal M (April 2002). "Intravenous ascorbic acid administration for erythropoietin-hyporesponsive anemia in iron loaded hemodialysis patients". Artificial Organs. 26 (4): 366–370. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1594.2002.06888.x. PMID 11952508.

- "Anaemia management in people with chronic kidney disease | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". Archived from the original on 2013-06-24. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- Auerbach M, Ballard H (2010). "Clinical use of intravenous iron: administration, efficacy, and safety". Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2010: 338–347. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.338. PMID 21239816.

- Kansagara D, Dyer E, Englander H, Fu R, Freeman M, Kagen D (December 2013). "Treatment of anemia in patients with heart disease: a systematic review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (11): 746–757. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-11-201312030-00007. PMID 24297191.

- Goddard AF, James MW, McIntyre AS, Scott BB (October 2011). British Society of Gastroenterology. "Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia". Gut. 60 (10): 1309–1316. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.228874. PMID 21561874.

- Preston, Nancy J.; Hurlow, Adam; Brine, Jennifer; Bennett, Michael I. (2012-02-15). "Blood transfusions for anaemia in patients with advanced cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD009007. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009007.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7388847. PMID 22336857.

- Aapro MS, Link H (2008). "September 2007 update on EORTC guidelines and anemia management with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents". The Oncologist. 13 Suppl 3 (Supplement 3): 33–36. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.13-S3-33. PMID 18458123.

- American Society of Nephrology, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Society of Nephrology, archived (PDF) from the original on April 16, 2012, retrieved August 17, 2012

- Kaufner L, Heymann C. "Erythropoietin plus iron versus control treatment including placebo or iron for preoperative anaemic adults undergoing non‐cardiac surgery". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012451.pub2.

- Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society. "Exceptional Blood Loss – Anemia". Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- Hart GB, Lennon PA, Strauss MB (1987). "Hyperbaric oxygen in exceptional acute blood-loss anemia". J. Hyperbaric Med. 2 (4): 205–210. Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- Van Meter KW (2005). "A systematic review of the application of hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of severe anemia: an evidence-based approach". Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine. 32 (1): 61–83. PMID 15796315. Archived from the original on 2009-01-16.

- Kaufner, Lutz; von Heymann, Christian; Henkelmann, Anne; Pace, Nathan L.; Weibel, Stephanie; Kranke, Peter; Meerpohl, Joerg J.; Gill, Ravi (2020-08-13). "Erythropoietin plus iron versus control treatment including placebo or iron for preoperative anaemic adults undergoing non-cardiac surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: CD012451. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012451.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 32790892.

- Kotzé, Alwyn; Harris, Andrea; Baker, Charles; Iqbal, Tariq; Lavies, Nick; Richards, Toby; Ryan, Kate; Taylor, Craig; Thomas, Dafydd (November 2015). "British Committee for Standards in Haematology Guidelines on the Identification and Management of Pre-Operative Anaemia". British Journal of Haematology. 171 (3): 322–331. doi:10.1111/bjh.13623. ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 26343392. S2CID 37709527.

- Tayles N (September 1996). "Anemia, genetic diseases, and malaria in prehistoric mainland Southeast Asia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 101 (1): 11–27. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199609)101:1<11::AID-AJPA2>3.0.CO;2-G. PMID 8876811.

External links

- "Anemia". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "The case for action on Anemia- leave no one behind". devex.com.

- "Interventions by global target". WHO.int.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |