Power of Women

The "Power of Women" (Weibermacht in German) is a medieval and Renaissance artistic and literary topos, showing "heroic or wise men dominated by women", presenting "an admonitory and often humorous inversion of the male-dominated sexual hierarchy".[2] It was defined by Susan L. Smith as "the representational practice of bringing together at least two, but usually more, well-known figures from the Bible, ancient history, or romance to exemplify a cluster of interrelated themes that include the wiles of women, the power of love, and the trials of marriage".[3] Smith argues that the topos is not simply a "straightforward manifestation of medieval antifeminism"; rather, it is "a site of contest through which conflicting ideas about gender roles could be expressed".[4][5]

Smith argues the topos originates in classical literature[6] and finds it in medieval texts such as Aucassin et Nicolette, The Consolation of Philosophy, the Roman de la Rose, and the Canterbury Tales.[7] The topos was attacked by Christine de Pizan around 1400, who argued that if women wrote these accounts their interpretations would be different from those of men.[8]

In the visual arts, images are found in various media, mainly from the 14th century onwards, and becoming increasingly popular in the 15th century. By then the frequently recurring subjects include Judith beheading Holofernes, Phyllis riding Aristotle, Samson and Delilah, Salome and her mother Herodias, Jael killing Sisera, Bathsheba bathing in sight of David, the idolatry of Solomon, Virgil in his basket, as well as many depictions of witches, and genre images of wives dominating their husbands. The last group came to be called the battle for the trousers.[9] Joseph and Potiphar's wife and Lot and his Daughters were somewhat late joiners to the group, but increasingly popular later on.[10] Tomyris, the Scythian queen who defeated Cyrus the Great and abused his corpse, was painted by Rubens and several Italians.[11]

These scenes, mostly shown in consistent compositions involving just two persons and visually distinctive actions, were easily recognisable and seem to have also been represented dramatically in entertainments of various sorts, whether as short scenes or tableaux vivants.[12] It is not clear who first coined the term Weibermacht, but it had evidently gained currency in the sixteenth century Northern Renaissance in Germany and the Low Countries.[13]

Visual arts

In early images from the Gothic period genre subjects or "classical" ones such as Phyllis Riding Aristotle and Virgil in his Basket, in fact both medieval legendary accretions, were more popular than the biblical ones predominating later. They often appear on the same pieces as the Assault on the Castle of Love, as on a casket in Baltimore. This and similar subjects of courtly love mostly survive on ivory objects for female use, such as caskets or mirror-cases. It shows ladies defending a castle against men, generally unsuccessfully.[14] These images are essentially light-hearted romantic fantasy given a comic treatment; such scenes were sometimes staged as light relief at tournaments.[15]

The Power of Women theme is especially popular in Northern Renaissance art from the sixteenth century, which depicts "images drawn from historical, mythological, and biblical sources that illustrate women's power over men, specifically as a result of their sexual attractiveness".[16] Several of the stories involve the killing of the male, and this and their religious context effectively remove much of the comic potential of the group, but by no means the erotic possibilities exploited by many artists.

The question of the attitudes shown towards violence by women in the cause of virtue is perhaps best seen in the figure of Jael, whose killing of Sisera by hammering a tent peg into his head makes an especially graphic image. According to some feminist critics, depictions of her turned hostile in the Renaissance, and like Judith she is certainly grouped with "bad" figures such as Herodias and Delilah. Yet she was included, with Judith and Esther, as one of Hans Burgkmair's "Drei Gut Judin" ("Three Good Jewesses") trio of Biblical heroines in his Eighteen Worthies, adding nine women to the traditional male Nine Worthies.[17]

The Power of Women subjects are seen in painting and other media, but prints were their special home. Lucas van Leyden made two sets of woodcuts known as The Large and Small Power of Women. The subjects featured include Adam and Eve, Samson and Delilah, King Solomon, Herod and Herodias, Jael and Sisera, and, less usually, Jezebel and King Ahab. The woodcuts have somewhat static compositions, and it has been suggested that they draw from tableaux vivants of the scenes.[18] Another set by Hans Burgkmair (1519) is known as the Liebestorheiten or Follies of Love.[19] At the same time there was also an interest, often among the same artists, in women from similar settings who were powerless, or only able to escape their situations by suicide, such as Susanna, Dido of Carthage, Lucretia, and Verginia.[20] The story of Esther lay somewhere between these two extremes.[21]

The Little Masters were among those artists greatly interested in both groups. The treatment of both groups, especially in prints, was often frankly erotic, and these groups took their place alongside female saints and lovers both mythological and realistic in the common treatments of women in art. Interest in such themes spread to Italy, affecting Venice first, and the subjects became common in Late Renaissance Italian painting, and even more so during the Baroque, perhaps culminating in the work of Artemisia Gentileschi, who painted nearly all the biblical Power of Women subjects, most more than once. While her choice of subjects is assumed to be driven by her difficult life, Cristofano Allori's best known work, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, uses as models his former mistress for Judith, with her mother as the maid, and a self-portrait for the head of Holofernes.[22]

In Northern painting, the Cranachs were the first artists to paint the subjects often.[23] In 1513 Lucas Cranach the Elder decorated the nuptial bed of John, Elector of Saxony with a set of scenes including The Idolatry of Solomon as well as Hercules and Omphale (see below) and the Judgement of Paris. The respective sons of the patron and artist, John Frederick I, Elector of Saxony and Lucas Cranach the Younger, generated another set of paintings, now in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister.[24] The possibility has been raised that some of the Cranach workshop's many Judiths are portraits of ladies at the Saxon court;[25] some other paintings of Jael certainly are portraits.

Themes and context

Several of these subjects contain a part-comical element of role reversal in a society that was essentially patriarchal, above all the "quintessential image from the Power of Women topos, Phyllis Riding Aristotle."[26] The story of Phyllis and Aristotle dates from the early 13th century (when the Lai d'Aristote was written) and became the subject of popular poems, plays and moralizing sermons.[27] The theme was first analysed by Natalie Zemon Davis in 1975,[28] who concluded that the "overall functions" of these reversals was that "they afforded an expression of, and an outlet for, conflicts about authority within the system; and they also provided occasions by which the authoritarian current in family, workshop, and political life could be moderated by the laughter of disorder and paradoxical play. Accordingly they served to reinforce hierarchical structure".[29]

The role reversal subject of Hercules and Omphale did not fit the main Power of Women trope, as Hercules' period serving Omphale was not caused by interaction between them, and they later married. It became popular from the 16th century, and the Cranach family painted many versions showing Omphale and her ladies dressing Hercules in drag.[30]

Phyllis Riding Aristotle was painted on the walls of several German town halls,[31] though the design Albrecht Dürer made for Nuremberg, as part of a Power of Women cycle, was never carried out.[32] Some sets of prints have ornamental borders that suggest they were intended to be pasted to walls, as many larger prints were. While many of the smaller prints were probably mostly seen by male collectors and their friends, these paintings and wall-mounted prints "must have been intended to entertain or amuse both men and women".[33] Some of the Florentine Otto prints, essentially designed for a female audience, show women triumphing over men, though most show pacific scenes of lovers.[34]

Other large prints intended for walls, where Power of Women subjects are especially common, adopt a different type of composition from the small prints with a few figures, showing large and well-populated panoramic scenes where the key figures can be hard to pick out. David and Bathsheba or Salome's story are set amid wide townscapes, and Judith kills Holofernes in a corner of a huge battle scene in front of a walled city.[35]

The association of witchcraft specifically and almost exclusively with women was a novelty of the late 15th century, for which the book Malleus Maleficarum (1486) remains an emblem, though its significance has been questioned. The interpretation of the many images of witches has been the subject of considerable scholarly interest in recent decades, and many differing interpretations have been put forward. As well as allowing scope for imaginative fantasy, an erotic element is clear, above all in the work of Hans Baldung Grien, the artist most associated with the subject. The seriousness with which either the artist or their audience took the reality of witchcraft has been questioned; to some extent these seem to have been the horror movies of their day.[36] The Witch of Endor was a previously obscure subject that allowed the combination of biblical and witchcraft interest.

Gallery

Assault on the Castle of Love, ivory mirror case, 1340–60, France

Assault on the Castle of Love, ivory mirror case, 1340–60, France Master of the Housebook, Aristotle and Phyllis, 15th-century engraving

Master of the Housebook, Aristotle and Phyllis, 15th-century engraving.jpg.webp) Phyllis and Aristotle by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1530

Phyllis and Aristotle by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1530 Master E.S., Samson and Delilah, 1460s

Master E.S., Samson and Delilah, 1460s The "Battle for the Trousers" motif: Israhel van Meckenem, The Angry Wife, genre engraving, 1490s[37]

The "Battle for the Trousers" motif: Israhel van Meckenem, The Angry Wife, genre engraving, 1490s[37] Another van Meckenem; here the man performs the normally female work of spinning while his partner threatens him with an elaborate object suggesting power.

Another van Meckenem; here the man performs the normally female work of spinning while his partner threatens him with an elaborate object suggesting power. Juan de Flandes, Herodias' Revenge, 1496

Juan de Flandes, Herodias' Revenge, 1496 Early 16th-century misericord of two women jousting, mounted on men, Walcourt, Belgium

Early 16th-century misericord of two women jousting, mounted on men, Walcourt, Belgium Lucas van Leyden, The Idolatry of Solomon, inspired by his pagan wife, from the "Large Power of Women" set of woodcuts, 1514[38]

Lucas van Leyden, The Idolatry of Solomon, inspired by his pagan wife, from the "Large Power of Women" set of woodcuts, 1514[38] Detail of a design for Nuremberg Town Hall, Albrecht Dürer, 1521

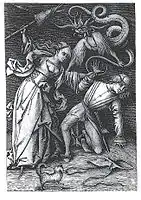

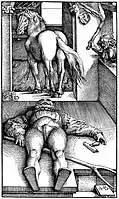

Detail of a design for Nuremberg Town Hall, Albrecht Dürer, 1521 Bewitched Stable Groom, Hans Baldung Grien, c. 1534[39]

Bewitched Stable Groom, Hans Baldung Grien, c. 1534[39] Sebald Beham, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, 1547[40]

Sebald Beham, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, 1547[40]

Notes

- "Aquamanile in the Form of Aristotle and Phyllis". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Ainsworth, p. 59

- Babinsky, Elen L. (1997). "Rev. of Smith, The Power of Women". Church History. 66 (2): 340–341. doi:10.2307/3170688. JSTOR 3170688.

- Smith, Susan L. (2006). Margaret Schaus (ed.). Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 844–845. ISBN 978-0415969444.

- c.f. Nurse p. 1, who characterises it as arising from the complex religious and social turmoil provoked by the European Reformation of the sixteenth century.

- Millett, Bella (22 September 1997). "Rev. of Smith, The Power of Women". Medium Aevum.

- Harp p. 208

- Wolfthal p. 57

- Salomon, 87; "strijd om de broek" in sixteenth century Netherlandish literature and printmaking.

- Russell, pp. 147–148, Nos 20–32 (Judith), 87–110, 120–125; Ainsworth, pp. 59–66; Salomon, pp. 87–88; Hall, 41–42

- Hall, 305

- Snyder, 461

- Nurse p. 1

- But not always. More typically the only real resistance is Cupid firing arrows.

- Loomis, Roger Sherman, "The Allegorical Siege in the Art of the Middle Ages", American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Jul.–Sep., 1919), pp. 255–269,JSTOR (free)

- Salomon, 87

- Russell, 29–39, No 1; Wolfthal, Diane (October 2000). Images of Rape: The Heroic Tradition and its Alternatives. Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN 0521794420; Bohn, Babette (2005). The Artemisia Files "Death, Dispassion and the Female Hero:Gentileschi's Jael and Sisera". Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226035824.

- Russell, pp. 119, 153, Large: Nos 90, 96, 100; Small: Nos 66, 92; Snyder, 461-462. The small set, of 1516–19 included the scenes with Eve, Jael, Delilah, Solomon, Jezebel and Herodias, the large set of c. 1512 added Virgil and the legend of the Bocca della Verità or "Mouth of Truth" in Rome. The Aristotle and Phyllis of c. 1515 is in the same format but may be a later addition. Since no museum has a full set on the same paper they may have been sold mainly singly.

- Russell, p. 160, Nos 94, 97. This set contains: Samson and Delilah, Bathsheba and David, The Idolatry of Solomon, and Phyllis riding Aristotle.

- Russell, Nos 1–14

- Russell, Nos 1, 15, 16

- Lucy Whitaker, Martin Clayton, The Art of Italy in the Royal Collection; Renaissance and Baroque, p.270, Royal Collection Publications, 2007, ISBN 9781902163291

- Ainsworth, p. 66

- Ainsworth, p. 62

- Ainsworth, pp. 63–66

- Russell, p. 175

- Boitani & Torti p. 82

- "Women on Top" in her Society and Culture in Early Modern France: Eight Essays, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1975

- Natalie Zemon Davis, "Women on Top", quoted by Russell, p. 175

- For a long analysis of the theme, see Rosenthal, Lisa, "Hercules' Distaff", especially p. 128 ff, in Gender, Politics, and Allegory in the Art of Rubens, 2005, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521842441, 9780521842440, Google Books

- Russell, p. 150; Parshall, pp. 234-235

- Foister p. 2

- Russell, p. 150; Parshall, pp. 234–235. Dürer's watercolour design is in the Morgan Library (see Commons image), and has roundels with Bathsheba and David, Samson and Delilah, and Phyllis riding Aristotle.

- example, British Museum. This collection, in the British Museum is the pattern book of a workshop probably making inserts for small boxes of sweet delicacies such as were given to the guests at weddings.

- Bartrum, p. 154, Nos. 96, 158, 160; Parshall, pp. 234-235

- Zika, Charles, "Images of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe", in Levack, Brian P. (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America, 2013, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199578168, 9780199578160, Google Books; Russell, pp. 14, 147–148, Nos 103–105; Harbison, Craig. The Art of the Northern Renaissance, pp. 120–121, 1995, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 0297835122; Bartrum, 69–70; there is a further account of the development of scholarship by Zika in pp. 48–65 here

- Russell, No. 125

- Russell, No. 100

- Russell, No. 105

- Russell, No. 28

References

- Ainsworth, Maryan Wynn, et al., German Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1350-1600, 2013, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), ISBN 1588394875, 9781588394873, google books

- Bartrum, Giulia; German Renaissance Prints, 1490–1550; British Museum Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-7141-2604-3

- Boitani, Piero; Torti, Anna (1999). The Body and the Soul in Medieval Literature. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9780859915458.

- Foister, Susan. "Dürer's Nuremberg Legacy" (PDF). British Museum.

- Hall, James, Hall's Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, 1996 (2nd edn.), John Murray, ISBN 0719541476

- Harp, Margaret (1996). "Rev. of Smith, The Power of Women". Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature. 50 (2): 208–10. doi:10.2307/1348248. JSTOR 1348248.

- Nurse, Julia (July 1998). "She-Devils, Harlots and Harridans in Northern Renaissance Prints". History Today. 48 (7).

- Parshall, Peter, in Landau, David, and Parshall, Peter. The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0300068832

- Russell, H Diane (ed), Eva/Ave; Women in Renaissance and Baroque Prints, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1990, ISBN 1558610391

- Salomon, Nanette (2004). Shifting Priorities: Gender and Genre in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Painting. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804744775.

- Snyder, James. Northern Renaissance Art, 1985, Harry N. Abrams, ISBN 0136235964

- Wolfthal, Diane. "Susan L. Smith, The Power of Women: A Topos in Medieval Art and Literature. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995" Medieval Feminist Newsletter 22 (1996)

Further reading

- Smith, Susan L., The Power of Women: A 'Topos' in Medieval Art and Literature., University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-8122-3279-0

- Tal, Guy, Witches on Top: Magic, Power, and Imagination in the Art of Early Modern Italy, Dissertation, Indiana University, 2006, Proquest, ISBN 0542847914, 9780542847912