Susanna (Book of Daniel)

Susanna (Hebrew: שׁוֹשַׁנָּה, Modern: Šošana, Tiberian: Šôšannâ: "lily"), also called Susanna and the Elders, is a narrative included in the Book of Daniel (as chapter 13) by the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church. It is one of the additions to Daniel, considered apocryphal by Protestants. It is listed in Article VI of the 39 Articles of the Church of England among the books which are read "for example of life and instruction of manners", but not for the formation of doctrine.[1] It is not included in the Jewish Tanakh and is not mentioned in early Jewish literature,[2] although the text does appear to have been part of the original Septuagint from the 2nd century BC,[3] and was revised by Theodotion, a Hellenistic Jewish redactor of the Septuagint text (c. 150 AD).

Summary

A fair Hebrew wife named Susanna was falsely accused by lecherous voyeurs. As she bathes in her garden, having sent her attendants away, two elders, having previously said goodbye to each other, bump into each other again when they spy on her bathing. The two men realize they both lust for Susanna. When she makes her way back to her house, they accost her, demanding she have sex with them. When she refuses, they have her arrested, claiming that the reason she sent her maids away was to be alone as she was having sex with a young man under a tree.

She refuses to be blackmailed and is arrested and about to be put to death for adultery when the young Daniel interrupts the proceedings, shouting that the elders should be questioned to prevent the death of an innocent. After being separated, the two men are cross-examined about details of what they saw but disagree about the tree under which Susanna supposedly met her lover. In the Greek text, the names of the trees cited by the elders form puns with the sentence given by Daniel. The first says they were under a mastic tree (ὑπο σχίνον, hypo schinon), and Daniel says that an angel stands ready to cut (σχίσει, schisei) him in two. The second says they were under an evergreen oak tree (ὑπο πρίνον, hypo prinon), and Daniel says that an angel stands ready to saw (πρίσαι, prisai) him in two. The great difference in size between a mastic and an oak makes the elders' lie plain to all the observers. The false accusers are put to death, and virtue triumphs.

Date and textual history

The Greek puns in the texts have been cited by some[4] as proof that the text never existed in Hebrew or Aramaic, but other researchers[5] have suggested pairs of words for trees and cutting that sound similar enough to suppose that they could have been used in an original. The Anchor Bible uses "yew" and "hew" and "clove" and "cleave" to get this effect in English.

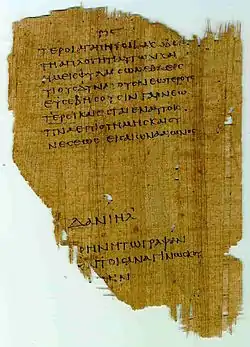

The Greek text survives in two versions. The received version is due to Theodotion; this has superseded the original Septuagint version, which now survives only in Syriac translation, in Papyrus 967 (3rd century), and exceptionally in a single medieval manuscript, known as Codex Chisianus 88.

Sextus Julius Africanus did not regard the story as canonical. Jerome (347–420), while translating the Vulgate, treated this section as a non-canonical fable.[6] In his introduction, he indicated that Susanna was an apocryphal addition because it was not present in the Hebrew text of Daniel. Origen received the story as part of the 'divine books' and censured 'wicked presbyters' who did not recognize its authenticity (Hom Lev 1.3.), remarking that the story was commonly read in the early Church (Letter to Africanus); he also noted the story's absence in the Hebrew text, observing (in Epistola ad Africanum) that it was "hidden" by the Jews in some fashion. Origen's claim is reminiscent of Justin Martyr's charge that Jewish scribes 'removed' certain verses from their Scriptures (Dialogue with Trypho: C.71-3). There are no known early Jewish references to the Susanna story.

Depictions in art

The story is portrayed on the Lothair Crystal, an engraved rock crystal made in the Lotharingia region of northwest Europe in the mid 9th century, now in the British Museum.[7]

The story was frequently painted from about 1470. Susanna is the subject of paintings by many artists, including (but not limited to) Lorenzo Lotto (Susanna and the Elders, 1517), Guido Reni, Rubens, Van Dyck (Susanna and the Elders), Tintoretto, Rembrandt, Tiepolo, and Artemisia Gentileschi. Some treatments, especially in the Baroque period, emphasize the drama, others concentrate on the nude; a 19th-century version by Francesco Hayez (National Gallery, London) has no elders visible at all.[8] The Uruguayan painter Juan Manuel Blanes also painted two versions of the story, most notably one where the two voyeurs are not in sight, and Susanna looks to her right with a concerned expression on her face.

In 1681 Alessandro Stradella wrote an oratorio in two parts La Susanna for Francesco II, Duke of Modena, based upon the story.

In 1749, George Frideric Handel wrote an English-language oratorio Susanna.

Susanna (and not Peter Quince) is the subject of the 1915 poem Peter Quince at the Clavier by Wallace Stevens, which has been set to music by the American composer Dominic Argento and by the Canadian Gerald Berg.

American artist Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975) painted a modern Susanna in 1938, now at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. He consciously included pubic hair, unlike the statue-like images of classical art. The fable was set during the Great Depression, and Benton included himself as one of the voyeurs.

The Belgian writer Marnix Gijsen borrows elements of the story in his first novel Het boek van Joachim van Babylon, 1947.

Pablo Picasso, too, rendered the subject in the mid-twentieth century, depicting Susanna much as he depicts his other less abstract reclining nudes. The elders are depicted as paintings hanging on the wall behind her. The picture, painted in 1955, is part of the permanent collection at the Museo Picasso Málaga.

The American opera Susannah by Carlisle Floyd, which takes place in the American South of the 20th century, is also inspired by this story, but with a less-than-happy ending and with the elders replaced by a hypocritical traveling preacher who rapes Susannah.

Shakespeare refers to this biblical episode in the trial scene of The Merchant of Venice, where first Shylock and then Gratiano praise Portia as being "A second Daniel" because of her sound judgments. Shakespeare is assumed to have named his eldest daughter after the biblical character.

The story is also repeated in the One Thousand and One Nights under the name The Devout Woman and the Two Wicked Elders.[9]

- Selected works

Susannah and the Elders by Massimo Stanzione. Städel

Susannah and the Elders by Massimo Stanzione. Städel Susannah and the Elders by Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari (late Baroque). The Walters Art Museum.

Susannah and the Elders by Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari (late Baroque). The Walters Art Museum. Susanna and the Elders by Alessandro Allori

Susanna and the Elders by Alessandro Allori Susannah and the Elders, Jan Matsys, The Phoebus Foundation

Susannah and the Elders, Jan Matsys, The Phoebus Foundation Susanna and Elders, 1860 woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld in Die Bibel in Bildern

Susanna and Elders, 1860 woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld in Die Bibel in Bildern Trial of Susanna, 1860 woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld in Die Bibel in Bildern

Trial of Susanna, 1860 woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld in Die Bibel in Bildern

References

- "Article VI at". Anglicansonline.org. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- "Jewishencyclopedia.com". Jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- New American Bible (Revised Edition), Footnote a

- Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Dunn, James D. G., 1939–, Rogerson, J. W. (John William), 1935–. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. 2003. p. 805. ISBN 9780802837110. OCLC 53059839.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Ball, Rev. Charles James (1888). The Holy Bible, According to the Authorized Version (A. D. 1611), with an Explanatory and Critical Commentary and a Revision of the Translation: Apocrypha, Volume 2. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street. p. 324. ISBN 9781276924047. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- Knights of Columbus Catholic Truth Committee (1908). The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church. Encyclopedia Press. p. 626. "Although the deutero-canonical portions of Daniel seem to contain anachronisms, they should not be treated – as was done by St. Jerome – as mere fables"

- British Museum. "Lothair Crystal". Collection online. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- "Susanna at her Bath, 1850, Francesco Hayez". Nationalgallery.org.uk. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- The Devout Woman and the Two Wicked Elders

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Susannah. |

- An illustrated story of Susanna and the Elders

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Susanna

- World Wide Study Bible: Susanna

- Daniel 13 in the New American Bible

- biblicalaudio Susanna (Daniel Chapter 13): 2013 Critical Translation with Audio Drama

%252C_Artemisia_Gentileschi.jpg.webp)