Power of a point

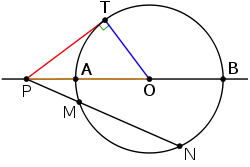

In elementary plane geometry, the power of a point is a real number h that reflects the relative distance of a given point from a given circle. Specifically, the power of a point P with respect to a circle O of radius r is defined by (Figure 1).

where s is the distance between P and the center O of the circle. By this definition, points inside the circle have negative power, points outside have positive power, and points on the circle have zero power. For external points, the power equals the square of the length of a tangent from the point to the circle. The power of a point is also known as the point's circle power or the power of a circle with respect to the point.

The power of point P (see in Figure 1) can be defined equivalently as the product of distances from the point P to the two intersection points of any line through P. For example, in Figure 1, a ray emanating from P intersects the circle in two points, M and N, whereas a tangent ray intersects the circle in one point T; the horizontal ray from P intersects the circle at A and B, the endpoints of the diameter. Their respective products of distances are equal to each other and to the power of point P in that circle

This equality is sometimes known as the "secant-tangent theorem", "intersecting chords theorem", or the "power-of-a-point theorem". In the case that P lies inside the circle, the two points of intersection will be on different sides of the line through P; the line can be considered to have a direction, so that one of the distances is negative, and therefore so is the product of the two.

The power of a point is used in many geometrical definitions and proofs. For example, the radical axis of two given circles is the straight line consisting of points that have equal power to both circles. For each point on this line, there is a unique circle centered on that point that intersects both given circles orthogonally; equivalently, tangents of equal length can be drawn from that point to both given circles. Similarly, the radical center of three circles is the unique point with equal power to all three circles. There exists a unique circle, centered on the radical center, that intersects all three given circles orthogonally, equivalently, tangents drawn from the radical center to all three circles have equal length. The power diagram of a set of circles divides the plane into regions within which the circle minimizing the power is constant.

More generally, French mathematician Edmond Laguerre defined the power of a point with respect to any algebraic curve in a similar way.

Orthogonal circle

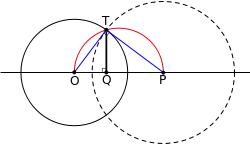

For a point P outside the circle, the power h =R2, the square of the radius R of a new circle centered on P that intersects the given circle at right angles, i.e., orthogonally (Figure 2). If the two circles meet at right angles at a point T, then radii drawn to T from P and from O, the center of the given circle, likewise meet at right angles (blue line segments in Figure 2). Therefore, the radius line segment of each circle is tangent to the other circle. These line segments form a right triangle with the line segment connecting O and P. Therefore, by the Pythagorean theorem,

where s is again the distance from the point P to the center O of the given circle (solid black in Figure 2).

This construction of an orthogonal circle is useful in understanding the radical axis of two circles, and the radical center of three circles. The point T can be constructed—and, thereby, the radius R and the power h found geometrically—by finding the intersection of the given circle with a semicircle (red in Figure 2) centered on the midpoint of O and P and passing through both points. It can also be shown that the point Q is the inverse of P with respect to the given circle.

Theorems

The power of a point theorem, due to Jakob Steiner, states that for any line through A intersecting a circle c in points P and Q, the power of the point with respect to the circle c is given up to a sign by the product

of the lengths of the segments from A to P and A to Q, with a positive sign if A is outside the circle and a negative sign otherwise: if A is on the circle, the product is zero. In the limiting case, when the line is tangent to the circle, P = Q, and the result is immediate from the Pythagorean theorem.

In the other two cases, when A is inside the circle, or A is outside the circle, the power of a point theorem has two corollaries.

- The chord theorem, theorem of intersecting chords, or chord-chord power theorem states that if A is a point inside a circle and PQ and RS are chords of the circle intersecting at A, then

- The common value of these products is the negative of the power of the point A with respect to the circle.

- The intersecting secants theorem (or secant-secant power theorem) states that if PQ and RS are chords of a circle which intersect at a point A outside the circle, then

- In this case the common value is the same as the power of A with respect to the circle.

- The tangent-secant theorem is a special case of the theorem of intersecting secants, where points Q and P coincide, i.e.

- This has utility in such applications as determining the distance to a point P on the horizon, by selecting points R and S to form a diameter chord, so that RS is the diameter of the planet, AR is the height above the planet, and AP is the distance to the horizon.

Darboux product

The power of a point is a special case of the Darboux product between two circles, which is given by

where A1 and A2 are the centers of the two circles and r1 and r2 are their radii. The power of a point arises in the special case that one of the radii is zero.

If the two circles are orthogonal, the Darboux product vanishes.

If the two circles intersect, then their Darboux product is

where φ is the angle of intersection.

Laguerre's theorem

Laguerre defined the power of a point P with respect to an algebraic curve of degree n to be the product of the distances from the point to the intersections of a circle through the point with the curve, divided by the nth power of the diameter d. Laguerre showed that this number is independent of the diameter (Laguerre 1905). In the case when the algebraic curve is a circle this is not quite the same as the power of a point with respect to a circle defined in the rest of this article, but differs from it by a factor of d2.

References

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (1969), Introduction to Geometry (2nd ed.), New York: Wiley.

- Darboux, Gaston (1872), "Sur les relations entre les groupes de points, de cercles et de sphéres dans le plan et dans l'espace", Annales Scientifiques de l'École Normale Supérieure, 1: 323–392.

- Laguerre, Edmond (1905), Oeuvres de Laguerre: Géométrie (in French), Gauthier-Villars et fils, p. 20

- Steiner, Jakob (1826), "Einige geometrische Betrachtungen", Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, 1: 161–184.

- Berger, Marcel (1987), Geometry I, Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-11658-5

Further reading

- Ogilvy C. S. (1990), Excursions in Geometry, Dover Publications, pp. 6–23, ISBN 0-486-26530-7

- Coxeter H. S. M., Greitzer S. L. (1967), Geometry Revisited, Washington: MAA, pp. 27–31, 159–160, ISBN 978-0-88385-619-2

- Johnson RA (1960), Advanced Euclidean Geometry: An elementary treatise on the geometry of the triangle and the circle (reprint of 1929 edition by Houghton Miflin ed.), New York: Dover Publications, pp. 28–34, ISBN 978-0-486-46237-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Power of a point. |

- Jacob Steiner and the Power of a Point at Convergence

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Circle Power". MathWorld.

- Intersecting Chords Theorem at cut-the-knot

- Intersecting Chords Theorem With interactive animation

- Intersecting Secants Theorem With interactive animation