Pre-industrial armoured ships

There are recorded incidents of armour having been employed in naval warfare in Europe and in East Asia prior to the introduction of the ironclad warship. Contemporary or later reports describe the use of metal plates on hulls or the superstructure of a limited number of wooden sailing ships, some of which were equipped with naval artillery. However, in every single case of both European and Far Eastern vessels the evidence for this is either unclear, ambiguous or disputed.

Evidence in Europe

Ship armour is to be distinguished from the practice of hull sheathing for preservational reasons, namely the protection against marine wood-boring worms. Greek merchantmen were fitted with lead sheets for that purpose by the 5th century BC.[1][2] A notable Roman example were the excavated Nemi Ships with an underwater hull covered by a thin layer of lead.[2] The practice was resumed by the Spanish and Portuguese in the Age of Exploration,[3] while the British Royal Navy began to copper their war ships in the 1760s.[4]

The huge Syracusia, built by the Greek tyrant Hiero II of Syracuse around 240 BC, featured bronze-clad mast-tops for marines and an iron palisade on its fighting deck against enemy boarding attempts.[5] Its hull was sheathed with lead plates fixed with bronze nails.[1] Roman naval cataphract warships were protected on their sides by a layer of tarred and lead sheathing. Although this does not provide much protection from ramming, it does provide protection from damage while at sea for lengthy periods of time.[6]

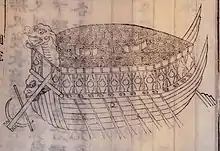

A few Norse longships were reinforced with iron armour along the waterline as early as the 11th Century, such as the Iron Beard of Eric Hakonsson of Norway.[7][8]

Peter IV of Aragon (1336–87) protected his ships with screens of hides against missile fire,[8] as the Roman navy had done earlier.[9]

A ship with iron plating on the ribs was commissioned in 1505 by Juan Lope de Lazcano, a Basque admiral of the Spanish Fleet.[10]

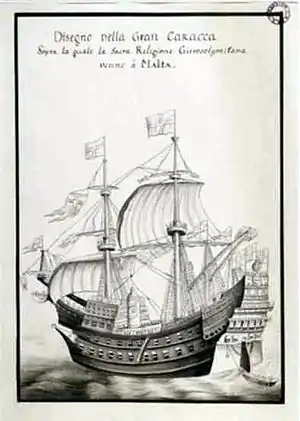

The Santa Anna, a lead-sheathed carrack of the Knights Hospitaller, is viewed by some authors as an early form of armoured ship.[8][11][12][13] From 1522 to 1540, the warship successfully operated in the Mediterranean Sea against the Turks.

The Galleon of Venice, the Venetian flagship which did serious damage to the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Preveza (1538), was sheathed with plate.[14]

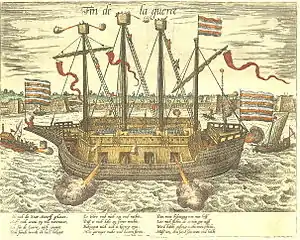

During the siege of Antwerp in 1585, the Dutch defenders partially protected their man-of-war Finis Bellis with iron plates.[15]

In 1782, Chevalier d'Arçon attacked Gibraltar with floating batteries featuring a 1.8 meter thick armour out of wooden planks, iron bars and leather, but met little success.[8]

Evidence in Eastern Asia

Early ship armour probably had its origins in applying thin sheets of metal to ship undersides for preservative reasons. In the Battle of Red Cliff in 208 AD, warships were covered with wetted hides as defense against incendiary weapons.[16] By 1130, in the battle of Huangtiandang, Jin sailors built protective bulwarks of an unknown material with oar ports in them, presumably as an adoptive response against its enemies.[17] The introduction of paddle-boats allowed the Song dynasty general Qin Shifu to build two new prototype warships. These warships were described to have their sides protected with iron plates.[18]

In 1578, Oda Nobunaga, the Japanese daimyō, had made six Atakebune (大安宅船) which were called, according to one source, Tekkōsen (鉄甲船|鉄甲船), literally meaning "iron ships".[19] implying that their superstructure may have been reinforced with iron plates against cannon and fire arrows.[19] These vessels, more floating batteries than ships, were armed with multiple cannons and large caliber arquebuses, and were described by the Italian Jesuit Organtino as being protected by iron plates two to three inches thick.[20] No iron-covering at all, however, was mentioned in the account of the Jesuit missionary Luís Fróis, who had also seen and described the ships.[21] Nobunaga defeated the navy of his enemy Mōri Terumoto with these ships at the mouth of the Kizu River, Osaka in 1578 with a successful naval blockade.

A possible usage of iron plates occurs during the 1592–1598 Imjin War when a single Japanese source mentions Korean turtle ships (Hangul:거북선, Geobukseon or Kobukson) to be "covered in iron".[24] A ship type named turtle ship appears as early as 1413 in Korean annals: "While passing by Imjin Island, the king viewed a kobukson and a Japanese ship fighting against each other." However, it seems to have subsequently faded into obscurity until resurrected and refined by Yi Sun-sin.[25] According to Stephen Turnbull, the Japanese responded by ordering supplies of iron plates for the building of warships, so that the turtle ship can be "countered in its own terms".[26]

According to Hawley, however, the Japanese phrase does not necessarily mean the vessels were covered with iron plates; it could simply refer to the iron spikes protruding from their roofs.[27] In fact, contemporary Korean sources do not support the claim that the turtle ships were ironclad:[28][29] Admiral Yi Sun-sin, the purported inventor himself, refers in his memoirs only to "iron spikes on its back to pierce the enemies' feet when they tried to board", but does not mention any iron plating.[28] Likewise Yi Pun, his nephew and war reporter, mentions in his lengthy war memoirs only "iron spikes" on the deck,[28] and the annals of king Seonjo, a comprehensive collection of official documents of the period, are silent, too, about any ironcladding.[28] Korean Prime Minister Ryu Seong-ryong described the turtle ship explicitly as "covered by wooden planks on top".[28]

See also

References

- D.J. Blackman: "Further Early Evidence of Hull Sheathing", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1972), pp.117-119

- Lionel Casson: Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World, The Johns Hopkins University Press 1995, ISBN 0-8018-5130-0, p.210, 214-216, 460

- Rudolph Rittmeyer: "Seekriege und Seekriegswesen in ihrer weltgeschichtlichen Entwicklung", E. S. Mittler, Berlin 1907

- Brian Lavery: The Arming and Fitting of English Ships of War 1600-1815, Conway Maritime Press Ltd 1999, ISBN 978-0-85177-451-0, p.62-65

- Jean MacIntosh Turfa, Alwin Steinmayer Jr: "The Syracusia as a Giant Cargo Vessel", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, Vol. 28, No. 2 (1999), pp. 105-125 (107-109)

- Workman-Davies, Bradley : "Corvus: A Review of the Design and Use of the Roman Boarding Bridge During the First Punic War 264 -241 B.C", pp. 85

- "Norseman News". Spring 2000. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- Meyers Konversationslexikon, 4th edition, 1888–1890, entry: Panzerschiff

- R. H. Dolley: "The Warships of the Later Roman Empire", The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 38, Parts 1 and 2 (1948), pp. 47-53 (50)

- Mark Kurlansky: The Basque History of the World, Walker & Company, New York 1999, ISBN 0-8027-1349-1, p. 56

- Jochen Brennecke: Geschichte der Schiffahrt, Künzelsau 1986 (2nd. ed.), p.138

- Brockhaus online: Malta

- H.J.A. Sire: "The Knights of Malta", Yale University Press 1996, ISBN 978-0-300-06885-6, p.88

- Ernle Dusgate Selby Bradford: "The Sultan's Admiral: The Life of Barbarossa", Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968, p.177

- J. Rudlov: "Die Einführung der Panzerung im Kriegschiffbau und die Entwicklung der ersten Panzerflotten", Beiträge zur Geschichte der Technik und Industrie, Vol. 2, No. 1 (1910)

- "Fighting ships of the Far-East (1)", Stephen Turnbull, p22

- Turnbull, Stephen: Fighting Ships of the Far East (1): China and Southeast Asia 202 BC-AD 1419

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 688.

- Stephen Turnbull, "Samurai Warfare" (London, 1996), Cassell & Co, p.102 ISBN 1-85409-280-4

- Boxer, C.R. (1993). The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650. Carcanet Press. p. 122. ISBN 1-85754-035-2.

- Stephen Turnbull, "Samurai Warfare" (London, 1996), Cassell & Co ISBN 1-85409-280-4, p.102f.

- Hawley, Samuel: The Imjin War. Japan's Sixteenth-Century Invasion of Korea and Attempt to Conquer China, The Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch, Seoul 2005, ISBN 89-954424-2-5, p.198

- Kim, Zae-Geun: An Outline of Korean Shipbuilding History, Korea Journal, Vol. 29, No. 10 (Oct. 1989), pp. 4–17 (10)

- "Fighting ships of the Far-East (2)", Stephen Turnbull, p18

- Hawley, Samuel 2005, p. 192f. (+ fn. 12))

- "Fighting ships of the Far-East (2)", Stephen Turnbull, p20

- Hawley, Samuel: The Imjin War. Japan's Sixteenth-Century Invasion of Korea and Attempt to Conquer China, The Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch, Seoul 2005, ISBN 89-954424-2-5, p.602

- Hawley, Samuel: The Imjin War. Japan's Sixteenth-Century Invasion of Korea and Attempt to Conquer China, The Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch, Seoul 2005, ISBN 89-954424-2-5, p.195f.

- Roh, Young-koo: "Yi Sun-shin, an Admiral Who Became a Myth", The Review of Korean Studies, Vol. 7, No. 3 (2004), p.13