Precursors to anarchism

Prior to the rise of anarchism as an anti-authoritarian political philosophy in the 19th century, both individuals and groups expressed some principles of anarchism in their lives and writings.

Antiquity

The longest period before recorded history human society was without a separate class of established authority or formal political institutions.[1][2] Long before anarchism emerged as a distinct perspective, human beings lived for thousands of years in self-governing societies without a special ruling or political class.[3] It was only after the rise of hierarchical societies that anarchist ideas were formulated as a critical response to and rejection of coercive political institutions and hierarchical social relationships.[4]

Ancient China

Taoism, which developed in ancient China, has been embraced by some anarchists as a source of anarchistic attitudes. The Taoist sages Lao Zi (Lao Tzu) and Zhuang Zhou whose philosophy was rather based on an "anti-polity" stance and rejection of any kind of involvement in political movements or organisations and developed a philosophy of "non-rule" in the Zhuang Zhou and Tao Te Ching, and many Taoists in response lived an anarchic lifestyle.[5] There is an ongoing debate whether exhorting rulers not to rule belongs to the sphere of anarchism.[6] A new generation of Taoist thinkers with anarchic leanings appeared during the chaotic Wei-Jin period. Taoist principles were more akin to philosophical anarchism, trying to delegitimate the state and question its morality. Taoism and neo-Taoism were pacifist schools of thought, in contrast with many of their Western anarchist counterparts some centuries later.[7]

Ancient Greece

Some convictions and ideas deeply held by modern anarchists were first expressed in ancient Greece.[8][9] The first known political usage of the word anarchy[lower-alpha 1] appears in the play Seven Against Thebes by Aeschylus, dated at 467 BC. There, Antigone openly refuses to abide by the rulers' decree to leave her brother Polyneices' body unburied as punishment for his participation in the attack on Thebes. Sophocles used the same theme 50 years later, in his tragedy Antigone, where the heroine challenges the established order of Thebes, coming in direct clash with the established authority of the town.[12]

Ancient Greece also saw the first Western instance of anarchic philosophical ideals, including those of the Cynics and Stoicists. The Cynics Diogenes of Sinope and Crates of Thebes are both supposed to have advocated anarchistic forms of society, although little remains of their writings. Their most significant contribution was the radical approach of nomos (law) and physis (nature). Contrary to the rest of Greek philosophy, aiming to blend nomos and physis in harmony, Cynics dismissed nomos (and in consequence: the authorities, hierarchies, establishments and moral code of the polis) while promoting a way of life, based solely on physis.[13][14] Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism who was much influenced by the Cynics, described his vision of an egalitarian utopian society around 300 BC.[15] Zeno's Republic advocates a anarchic form of society in which there is no need for state structures. He argued that although the necessary instinct of self-preservation leads humans to egotism, nature has supplied a corrective to it by providing man with another instinct, namely sociability. Like many modern anarchists, he believed that if people follow their instincts, they will have no need of law courts or police, no temples and no public worship and use no money (free gifts taking the place of the exchanges).[1][16]

Socrates, as appropriate to anarchism, constantly questioned authority and centred his philosophy upon every man's right to freedom of consciousness.[17] Aristippus, a pupil of Socrates and founder of the Hedonistic school, claimed that he wished neither to rule nor be ruled, and also he saw the state as a danger to personal autonomy.[13] Not all in ancient Greece had anarchic tendencies though, other philosophers as Plato and Aristotle used the term anarchy negatively in association with democracy which they mistrusted as inherently vulnerable and prone to deteriorate into tyranny.[18]

Middle Ages

Medieval Asia

In medieval Persia, Mazdak, a Zoroastrian prophet and heretic now considered a proto-socialist, called for free love, abolition of private property and overthrow of the king.[19][20] He saw sharing as a religious duty and that no one should have more than others, though sources dispute whether he advocated communal ownership or redistribution. The latter claim being that he gave land, possessions, women and slaves from the rich to the poor.[20] He and his thousands of followers were massacred in 582 CE but his teaching went on to influence Islamic sects of the following centuries.[19]

A theological form on anarchic Islam developed in Basra and Baghdad among Mu'tazilite ascetics and Najdiyya Kharijites. This Islamic tendency was not communist or egalitarian and did not resemble current concepts of anarchism, but preached that the state was harmful, illegitimate, immoral and unnecessary.[21]

Medieval Europe

In Europe, Christianity was overshadowing all aspects of life. Brethren of the Free Spirit was the most notable example of heretic belief that had some vaguely anarchic tendencies. They held anticleric sentiments and believed in total freedom. Even though most of their ideas were individualistic, the movement had a social impact, influencing riots and rebellions in Europe for years to come.[22] Other anarchistic religious movements in Europe during the Middle Ages, include the Hussites, Adamites and the early Anabaptists.[23]

Early modern era

20th century historian James Joll describes anarchist history as two opposing sides. One, the zealotic and ascitic religious movements of the Middle Ages which rejected institutions, laws, and the established order. The other, the theories of the 18th century based on rationalism and logic. According to Joll, these two currents later blended to form a contradictory movement that nonetheless resonated to a very broad audience.[24]

Renaissance

With the spread of Renaissance across Europe, anti-authoritarian and secular ideas re-emerged. The most prominent thinkers advocating for liberty, mainly French, were employing Utopia in their works, to bypass strict state censorship. In Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532–1552), François Rabelais wrote of the Abby of Thelema (Greek word meaning "will" or "wish"), an imaginary utopia whose motto was "Do as Thou Will". Around the same time, the French law student Etienne de la Boetie wrote his Discourse on Voluntary Servitude in which he argued that tyranny resulted from voluntary submission and could be abolished by the people refusing to obey the authorities above them. Later, still in France, Gabriel de Foigny perceived an Utopia with freedom-loving people without government and no need of religion, as he wrote in The Southern Land, Known. Geneva authorities jailed Foigny for that book. Fenelon also used Utopia to project his political views, in a book (Telemaque) that infuriated Louis XIV.[25]

Early Protestantism

Some Reformation currents (like radical reformist movement of Anabaptists) are sometimes accredited as the religious forerunners of modern anarchism. Even though it was a religious revolution and strengthened the state, it also open the road for the humanistic values of the French Revolution.[26] In England during the English Civil War Christian anarchism found one of its most articulate forerunners in Gerrard Winstanley, who was part of the Diggers movement. Winstanley published a pamphlet calling for communal ownership and social and economic organization in small agrarian communities. Drawing on the Bible, he argued that "the blessings of the earth" should "be common to all" and "none Lord over others".[1]

In the New World, religious dissenter Roger Williams founded the colony of Providence, Rhode Island after being run out of the theocratic Puritan Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1636. Unlike the Puritans, he scrupulously purchased land from local American Indians for his settlement.[27] The Quaker sect, mostly because of their pantheism, had some anarchic tendencies—values that would later influence Benjamin Tucker.[28][29] The first to use the term "anarchy" to mean something other than chaos was Louis-Armand, Baron de Lahontan in his Nouveaux voyages dans l'Amérique septentrionale (New Voyages in Northern America, 1703), where he described the indigenous American society which had no state, laws, prisons, priests or private property as being in anarchy.[30] William Blake has also been said to espouse an anarchistic political position.[18]

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment saw a further eruption of secular and humanistic thought. The scientific discoveries that preceded the Enlightenment gave confidence to thinkers of the time that humans could reason for themselves and when nature was tamed through science, society could be set free. Liberal concepts prior to anarchism developed in the works of Jean Meslier, Baron d'Holbach, whose materialistic worldview later resonated with anarchists, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, especially in his Discourse on Inequality and arguments for the moral centrality of freedom. Rousseau affirmed the goodness in the nature of men and viewed state as fundamentally oppressive. Denis Diderot's The Supplement to the Voyage of Bougainville was also influential.[31][32]

Late modern era

French Revolution

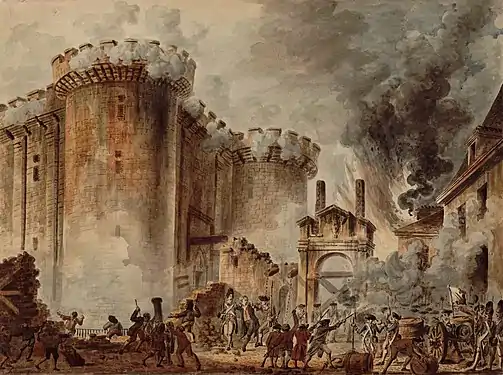

The French Revolution has been a landmark in the history of anarchism. The use of revolutionary violence by masses to achieve political ends has been in the imaginary of anarchists of the forthcoming centuries and events as Women's March on Versailles, the Storming of the Bastille or the Réveillon riots were seen as the revolutionary archetype.[33] In his "Manifesto of the Equals", Sylvain Maréchal looked forward to the disappearance, once and for all, of "the revolting distinction between rich and poor, of great and small, of masters and valets, of governors and governed".[1] Anarchists would identify themselves with the enrages or sans-culottes-The Enragés (Enraged Ones) opposed revolutionary government as a contradiction in terms. Denouncing the Jacobin dictatorship, Jean Varlet wrote in 1794 that "government and revolution are incompatible, unless the people wish to set its constituted authorities in permanent insurrection against itself".[1][34] French Revolution depicted in the common subconscious of anarchists that as soon as the rebels seize power, they would become the new tyrants, something that was evident by the State orchestrated violence of the Reign of Terror. The proto-anarchist groups of enrages and sans-culottes were ultimately erased at the edge of the guillotine.[35]

The debate of the effects of the French Revolution to the anarchist causes spans to our days. Anarchist historian Max Nettlau, French revolutions did nothing more than re-shaping and modernizing the militaristic state[36] while Kropotkin on the other hand, traced the origins of the anarchist movement in the struggle of the revolutionaries.[37] In a more moderate approach, Sean Sheehan points out that the French Revolution proved that even the strongest political establishments can be overthrown.[38]

Notes

References

- Graham 2005, pp. xi-xiv.

- Ross 2019, p. ix.

- Barclay 1990, pp. 39–42.

- Barclay 1990, pp. 15–16.

- Graham 2005, p. 1.

- Rapp 2012, p. 20.

- Rapp 2012, pp. 45–46.

- Woodcock 1962, p. 38.

- Long 2013, p. 217.

- Histories IX, 23, quote (in ancient greek)=ἐδόκεε δέ σφι ἀναρχίης ἐούσης ἀπελαύνειν παρὰ Μαρδόνιον

- Jun & Wahl 2010, p. 68: Iliad II, 703. , quote (in ancient greek) = "οὐδὲ μὲν οὐδ᾽ οἳ ἄναρχοι ἔσαν, πόθεόν γε μὲν ἀρχόν"

- Jun & Wahl 2010, pp. 68–70: Antigones famous words:"even if no one else is willing to share in burying him I will bury him alone and risk the peril of burying my own brother. Nor am I ashamed to act in defiant opposition to the rulers of the city (Ἒχουσα ἄπιστων τήν ἀναρχίαν πόλει; Ekhousa apistõn tēn anarkhian polei)"

- Marshall 1993, p. 68.

- Fiala 2017.

- Schofield 1999, p. 56.

- Marshall 1993, p. 7071.

- Marshall 1993, p. 67.

- Goodway 2006, p. 5.

- Marshall 1993, p. 86.

- Crone 1991, p. 24.

- Crone 2000, pp. 3, 21–25: Anarchist historian David Goodway is also convinced that the Muslim sects e Mu'tazilite and Najdite are part of anarchist history. (Interview at The Guardian Wed September 7, 2011)

- Marshall 1993, pp. 86–89: Marshall mentions the "English Peasants' Revolt in 1381, the Hussite Revolution in Bohemia at Tabor in 1419–1421, the German Peasants' Revolt by Thomas Munzer in 1525, and Munster Commune του 1534"

- Nettlau 1996, p. 8.

- Joll 1975, p. 23.

- Marshall 1993, pp. 108–114.

- McLaughlin 2007, pp. 102-104 & 141.

- Foster 1886.

- Marshall 1993, pp. 102–104 & 389.

- Woodcock 1962, p. 43.

- Lehning 2003.

- McKinley 2019, pp. 307–310.

- McLaughlin 2007, p. 102.

- McKinley 2019, pp. 311–312.

- McKinley 2019, p. 311.

- McKinley 2019, p. 313.

- Nettlau 1996, pp. 30–31.

- Marshall 1993, p. 432.

- Sheehan 2003, pp. 85–86.

Bibliography

- Barclay, Harold B. (1990). People without government: an anthropology of anarchy. Kahn & Averill. ISBN 978-1-871082-16-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crone, Patricia (1991). "Kavad's Heresy and Mazdak's Revolt" (PDF). Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 29: 21–40.

- Crone, Patricia (2000). "Ninth-Century Muslim Anarchists" (PDF). Past & Present. 167: 3–28. doi:10.1093/past/167.1.3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- D'Agostino, Anthony (2019). "Anarchism and Marxism in the Russian Revolution". In Levy, Carl; Adams, Matthew S. (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Acosta, Alejandro (2009). "Two undecidable questions for thinking in which anything goes". In Randall Amster (ed.). Contemporary Anarchist Studies: An Introductory Anthology of Anarchy in the Academy. Luis Fernandez, Abraham DeLeon. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47402-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fiala, Andrew (October 3, 2017). "Anarchism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved January 14, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foster, William E. (1886). Town government in Rhode Island. Baltimore : Johns Hopkins Press. Retrieved December 23, 2008 – via Internet Archive.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodway, David (2006). Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow: Left-libertarian Thought and British Writers from William Morris to Colin Ward. PM Press. ISBN 978-1-60486-221-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Graham, Robert (2005). "Preface". Anarchism: a Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas: from Anarchy to Anarchism. Montréal: Black Rose Books. ISBN 978-1-55164-250-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joll, James (1975). The anarchists. Επίκουρος(Greek edition). ISBN 9780674036413.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jun, Nathan J.; Wahl, Shane (2010). New Perspectives on Anarchism. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7391-3241-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lehning, Arthur (2003). "Anarchism". Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Archived from the original on September 9, 2006. Retrieved December 23, 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Long, Roderick T. (2013). Gerald F. Gaus; Fred D'Agostino (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Social and Political Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87456-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marshall, Peter H. (1993). Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. Fontana. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKinley, C. Alexander (2019). "The French Revolution and 1848". In Levy, Carl; Adams, Matthew S. (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McLaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-18151-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nettlau, Max (1996). A Short History of Anarchism. Freedom Press. ISBN 978-0-900384-89-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rapp, John A. (August 9, 2012). Daoism and Anarchism: Critiques of State Autonomy in Ancient and Modern China. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4411-3223-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ross, Carne (2019). "Preface". In Levy, Carl; Adams, Matthew S. (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schofield, Malcolm (July 1999). The Stoic Idea of the City. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-74006-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheehan, Seán (2003). Anarchism. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-169-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodcock, G. (1962). Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Melbourne: Penguin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bucci, John (1971). "Searching for the Meaning of Anarchism". The Journal of Education. 154 (2): 61–68. doi:10.1177/002205747115400210. ISSN 0022-0574. JSTOR 42773032.

- Graham, Robert (2013). "The Anarchist Current: Continuity and Change in Anarchist Thought". Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas. 3. Montreal: Black Rose Books. pp. 475–587. ISBN 978-1-55164-337-3. OCLC 824655763.

- Levy, Carl; Adams, Matthew S., eds. (2018). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 127. ISBN 978-3-319-75619-6.

- Marshall, Peter H. (2010) [1992]. "Forerunners of Anarchism". Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. Oakland, CA: PM Press. pp. 51–139. ISBN 978-1-60486-064-1.

- McLaughlin, Paul (2007). "The Historical Foundations of Anarchism". Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Ashgate. pp. 101–116. ISBN 978-0-7546-6196-2.