Predominant chord

In music theory, a predominant chord (also pre-dominant[3]) is any chord which normally resolves to a dominant chord.[3] Examples of predominant chords are the subdominant (IV, iv), supertonic (ii, ii°), Neapolitan sixth and German sixth.[3] Other examples are the secondary dominant (V/V) and secondary leading tone chord. Predominant chords may lead to secondary dominants.[4] Predominant chords both expand away from the tonic and lead to the dominant, affirming the dominant's pull to the tonic.[5] Thus they lack the stability of the tonic and the drive towards resolution of the dominant.[5] The predominant harmonic function is part of the fundamental harmonic progression of many classical works.[6] The submediant (vi) may be considered a predominant chord or a tonic substitute.[7]

| Look up predominant chord in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The dominant preparation is a chord or series of chords that precedes the dominant chord in a musical composition. Usually, the dominant preparation is derived from a circle of fifths progression. The most common dominant preparation chords are the supertonic, the subdominant, the V7/V, the Neapolitan chord (N6 or ♭II6), and the augmented sixth chords (e.g., Fr+6).

In sonata form, the dominant preparation is in the development, immediately preceding the recapitulation. Ludwig van Beethoven's sonata-form works generally have extensive dominant preparation — for example, in the first movement of the Sonata Pathétique, the dominant preparation lasts for 29 measures (mm. 169–197).

List

|

|

Gallery

ii-V-I turnaround in C ( |

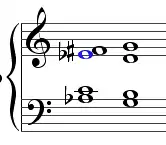

The French sixth chord; distinguishing tone highlighted in blue. |

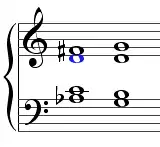

The German sixth; the distinguishing tone is highlighted in blue. |

|

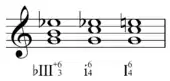

Three examples |

See also

Sources

- Adapted from Piston W (1962) Harmony, 3rd ed., NY, Norton, p. 96.

- Berry, Wallace (1987). Structural Functions in Music, p.54. ISBN 0-486-25384-8.

- Benward & Saker (2009). Music in Theory and Practice: Volume II, Glossary, p.359. Eighth Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0. "Any chord in functional harmony that normally resolves to the dominant chord."

- Benjamin, Thomas; Horvit, Michael; Koozin, Timothy; and Nelson, Robert (2014). Techniques and Materials of Music, p.149, 176. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781285965802.

- Cleland, Kent D. and Dobrea-Grindahl, Mary (2013). Developing Musicianship Through Aural Skills: A Holistic Approach to Sight Singing and Ear Training, p.255. Routledge. ISBN 9781135173067.

- Bartlette, Christopher, and Steven G. Laitz (2010). Graduate Review of Tonal Theory, pp.73–6. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537698-2

- Caplin, William E. (2013). Analyzing Classical Form: An Approach for the Classroom, p.10. Oxford. ISBN 9780199987306.

- Benjamin, Horvit, Koozin, and Nelson (2014), p.253.

- Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony in Concept and Practice, p.95. 3rd edition. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 0030207568. "Similarly, VI often serves as a stepwise dominant preparation."

- Benjamin, Horvit, and Nelson (2007), p.239. "A progression analogous to IV-V."

- Caplin, William E. (1998). Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, p.23. Oxford. ISBN 9780199881758.