Pro Quinctio

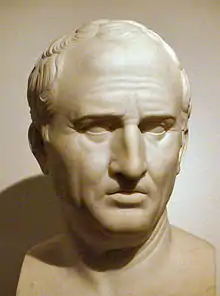

Pro Quinctio was a defence speech delivered by Marcus Tullius Cicero in 81 BC, on behalf of Publius Quinctius. It is noteworthy as the earliest of Cicero's published speeches to survive.

Background

The speech is a private legal case, centred around the business relationship between Gaius Quinctius and Sextus Naevius. The two were close partners (socii) for many years, with Naevius even marrying Gaius' cousin. Their chief investments were in cattle farms and land in Gallia Narbonensis.[1]

Death of Gaius Quinctius

When Gaius died suddenly in ca. 84 BC, he left his brother, Publius Quinctius, as his heir. Publius also inherited Gaius' outstanding debts, and intended to sell some of his own private property to pay them off. However, Naevius convinced him not to do so, and offered to advance the money required. The amount Publius was to pay was settled in Rome by Gaius Aquilius, a noteworthy iudex.[2]

When Publius Quinctius came to pay the debts, Naevius refused to grant the promised money until they had settled various unresolved issues about the partnership in Gaul. As a result, Publius was forced to sell his private property after all. The two now agreed to a vadimonium (a settlement in the courts), apparently to settle the terms of the partnership's dissolution.[3] At this vadimonium, Naevius announced that he had unilaterally sold part of the partnership's jointly owned property, and that he no longer considered there to be any unresolved issues: he then invited Publius to call another vadimonium in objection, but Publius declined. As a result, the two parties left without any agreement to appear in court again (at least according to Cicero's narrative of events).[4][5]

Violent dispute

However, matters soon turned violent. On 29 January 83 BC, Publius set off from Rome for Gaul, accompanied with some slaves he intended to sell there. Hearing of this, Naevius quickly gathered a number of friends, and (according to Cicero) pretended that a vadimonium had been called. With these friends as witnesses, he announced that Publius had failed to attend the vadimonium: as a result, he was able to obtain an edict from a praetor, Burrienus, announcing Publius as a defaulting debtor, and granting Naevius permission to seize his property.[6] Naevius' men attempted to seize the slaves Publius was planning to sell, but Publius' agent Alfenus prevented this by tearing down the placard announcing Burrienus' edict. However, when Publius arrived in Gaul a few days later, Naevius' men successfully ejected him from his property and forcibly seized the land.[7]

Sponsio

A number of appeals and disagreements followed over the next two years, including an attempted intervention on Publius’ behalf by the ex-consul and governor of Gallia Transalpina, Gaius Valerius Flaccus. Eventually, in 81 BC a praetor, Gnaeus Dolabella, forced Publius to enter a judicial wager (sponsio), in which Publius would try to establish that his property had not been seized according to Burrienus' edict.

The judge for the trial was Gaius Aquilius, the same jurist who had handled the initial stages of the case. Publius initially chose a Marcus Junius as his representative, but at the last minute had to hire the young Cicero, aged only 25, as replacement.[8][9] In contrast, Naevius hired the experienced Quintus Hortensius, by then the foremost orator in Rome: in addition, Hortensius was aided by Lucius Marcius Philippus, a former consul and one of the most influential members of Sulla's regime.[10]

Although it is Cicero's earliest surviving speech, it was not his first appearance as an advocate, as he makes a number of references throughout to earlier cases he had undertaken.

The speech

Cicero's argument

As per the terms of the sponsio, Cicero's speech focusses on whether Publius Quinctius' lands were lawfully seized according to the terms of Burrienus' edict. The speech is divided into three main arguments:

1.) Naevius should not have applied to Burrienus for the edict: firstly, because Publius owed Naevius no money; and secondly, because the additional vadimonium, which Naevius claimed Publius had failed to attend, was in fact never arranged at all.

2.) Naevius' possession of Publius' property cannot be 'in accordance with' Burrienus' edict, because none of the edict's conditions applied to Publius.

3.) given that the time between Naevius' application for the edict in Rome (20 February 83 BC) and his seizure of Publius' lands in Gaul (23 February) was so short, he must have treacherously pre-planned the event.

Throughout the speech, Cicero focusses on the influence, power, and arrogance of Naevius and his supporters. In contrast to the nefarious Naevius, Cicero emphasises the pitiable position of Publius Quinctius, whom he characterises as an honest, hardworking farmer, treacherously deprived of his familial property by a man who was meant to be his friend and partner. Given that Rome was in the midst of Sulla's dictatorship and the proscriptions, Cicero also takes the opportunity to highlight the general lawlessness and insecurity of the times, but falls short of criticising Sulla directly.[11] He was to take a similar approach in his next major speech, the pro Roscio Amerino of 80 BC.

Outcome

The result of the case is unknown. However, some scholars suggest that Cicero may have won, as he was unlikely to publish the speech so early in his career had it been a failure.[12]

References

- C. D. Yonge, The Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, Vol. 1., London, 1856; Johannes Platschek, Studien zu Ciceros Rede für P. Quinctius (Munich, 2005)

- J. H. Freese, Cicero: the Speeches (London, 1930), pp. 2–8.

- Cicero, pro Quinctio 22

- Cicero, pro Quinctio 14–24

- J. H. Freese, Cicero: the Speeches (London, 1930), pp. 2–8.

- Cicero, pro Quinctio 24–26

- A. Lintott, Cicero as Evidence (Oxford, 2008), p. 51

- Cicero, pro Quinctio 3

- Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 15.28

- J. H. Freese, Cicero: the Speeches (London, 1930), p. 8.

- A. Vasaly, 'Cicero's early speeches', in J.M. May (ed.), Brill's Companion to Cicero (Leiden, 2002), pp. 72–76

- E.g. A. Lintott, Cicero as Evidence (Oxford, 2008), p. 58