Provisional Cavalry

The Provisional Cavalry was a force levied in Great Britain from 1796 for home defence and organised at the county level. The unit was raised by an Act of Parliament instigated by the Secretary of State for War Henry Dundas who thought light cavalry would be particularly effective against any invading force. It was filled by means of an obligation from Britain's horse owners, who had to provide one trooper for every ten horses owned – a method which drew comparisons to the feudal system. Each county had a quota of cavalrymen that it was expected to provide. The act was unpopular and the number and quality of recruits was low.

| Provisional Cavalry | |

|---|---|

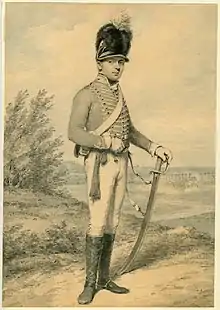

Major William Hallett of the Berkshire Provisional Cavalry | |

| Active | 1796–1802 |

| Country | |

| Type | Auxiliary cavalry |

| Role | Light cavalry |

Dundas preferred the Yeomanry Cavalry system of volunteers and in 1798 instigated measures to increase their numbers, exempting counties from the obligation to raise Provisional Cavalry where the Yeomanry could provide at least 75% of the demanded quota. This proved highly effective with the number of Yeomanry exceeding Dundas' expectations. The Provisional Cavalry was disbanded by 1802 and the enabling act was allowed to lapse in 1806.

Origins

Britain in early 1796 was in the midst of the French Revolutionary Wars and following defeats of her allies on the continent feared invasion. These fears later proved well founded with the occurrence of the December 1796 French expedition to Ireland and the February 1797 landings at Fishguard.[1] The British government became concerned that there were too few cavalrymen in the existing British Volunteer Corps (known as Yeomanry Cavalry). Cavalry were thought to be essential in defeating an invading force, which would be hampered by the limited number of horses it could bring by ship. At the proposal of the Secretary of State for War, Henry Dundas, parliament passed the Provisional Cavalry Act in 1796. This act established the Provisional Cavalry, which was liable for service anywhere in the country (some militia units were liable for service only within their own counties). Dundas was also responsible for raising the Fencibles and the Supplementary Militia for home defence.[2]

The Provisional Cavalry was raised by imposing liabilities upon those men in the country that owned horses. Those liable were required to provide one cavalry trooper for every ten horses owned (those who owned fewer than ten horses were collected into groups which were each required to provide one man).[3] The method of recruitment has been described as a form of revival of the feudal system whereby vassals were required to provide a quota of knights for their lord.[4] The British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger set an expected strength for the Provisional Cavalry of 20,000 men.[5]

Service

Unlike the yeomanry cavalry, who were paid only when called up, troopers of the provisional cavalry received a wage.[1] They sometimes took part in military exercises and camps with the yeomanry.[1] A quota was established for each county that it was expected to keep. However the Provisional Cavalry was unpopular, being a drain on the county funds and effectively conscripting members of the landowning class.[6] The Provisional Cavalry levies of 1797 failed to provide the minimum numbers that Dundas had set. In March of that year Colonel Mark Wood decried the unit in a parliamentary speech as an "unpopular measure ... so little calculated to afford any adequate degree of security to the public".[6][7] Roman Catholics were prohibited from serving in the unit, though William Wilberforce campaigned for them to be allowed to do so.[8]

Dundas described his intentions for the various cavalry units in case of an invasion. The regular cavalry was to attack the enemy, the Yeomanry to preserve the peace in civilian areas and the Provisional Cavalry to drive away cattle and carry out similar duties of a "hussar nature".[9] A near contemporary press report stated that the provisional cavalry was not dependable as a fighting force and might only be useful as escorts for baggage and provisions; though the writer also stated that a select few of the younger and more active members might have been useful as light cavalry if placed under experienced officers.[10]

Decline and disbandment

Dundas seems to have come to the conclusion that the volunteer Yeomanry provided a more effective force and that if it could be increased to sufficient numbers could supersede the Provisional Cavalry.[6] In May 1798 Dundas exempted Yeomanry men from being selected for service in the Provisional Cavalry (the Volunteer Corps infantry were exempted in 1799).[6] He also allowed counties to absolve themselves of the need for raising Provisional Cavalry if their Yeomanry regiments could muster more than 75% of the cavalry quota.[6][11] This led to a rapid increase in the ranks of the Yeomanry Cavalry – in the first six months of 1798 their number increased from less than 10,000 to more than 22,000. The Buckinghamshire Yeomanry expanded from six troops in 1794 to more than 50 in 1798, easily satisfying Dundas' quota for the county.[1][6]

The yeomanry were cheaper to raise and maintain, easier to train and proved more willing to serve when commanded. Despite this Dundas was initially keen to retain the provisional cavalry in counties where effective forces had been raised but, convinced by the rapid expansion in Yeomanry, was soon making arrangements to retire the force.[6] Dundas made the first arrangements to disband units of the Provisional Cavalry in June 1798 and within a year of doing so the numbers of Yeomanry had reached levels that exceeded what Dundas considered the maximum that was useful for the defence of the country.[6] Only six regiments of Provisional Cavalry were ever embodied, and only the provisional cavalry of Worcestershire was called upon to serve – doing so in Ireland.[12] Units that were not embodied were absorbed into the Yeomanry where they were often ostracised for their lower social status.[12] By 1800, the embodied units had been disbanded,[12] and the Provisional Cavalry as a distinct organisation was disbanded with the Peace of Amiens in 1802.[4] The parliamentary act enabling the recruitment of the Provisional Cavalry was allowed to lapse by the government in 1806.[6][13]

References

- Gee, Austin (2003). The British Volunteer Movement, 1794-1814. Clarendon Press. p. 37. ISBN 9780199261253. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Life of William Pitt, Late Prime Minister of Great Britain,: With Biographical Notices of His Principal Friends and Illustrious Contemporaries. J. Watts, Philadelphia, J. Osborne, New York. 1806. p. 129. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Buckinghamshire – Provisional Cavalry 1797. Booklet: Eureka Partnership. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 916.

- Cookson, J. E. (1997). The British Armed Nation, 1793-1815. Clarendon Press. p. 36. ISBN 9780198206583. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Cookson, J. E. (1997). The British Armed Nation, 1793-1815. Clarendon Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780198206583. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Parliament, Great Britain; Almon, John; Debrett, John; Stockdale, John (1797). The Parliamentary Register. J. Almon. p. 167. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Parliament, Great Britain; Almon, John; Debrett, John; Stockdale, John (1797). The Parliamentary Register. J. Almon. p. 533.

- Cookson, J. E. (1997). The British Armed Nation, 1793-1815. Clarendon Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780198206583. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- The Literary Panorama, and National Register. Cox, Son, and Baylis. 1808. p. 817. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "The learned pig". British Museum. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Beckett, Ian Frederick William (2011). Britain's Part-Time Soldiers: The Amateur Military Tradition: 1558–1945. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military. p. 77. ISBN 9781848843950.

- Aylward, J. D. (1956). The English Master of Arms: From the Twelfth to the Twentieth Century. Taylor & Francis. p. 216.