Public-key cryptography

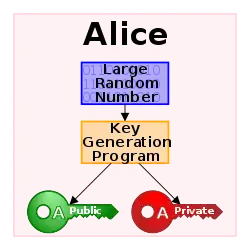

Public-key cryptography, or asymmetric cryptography, is a cryptographic system which uses pairs of keys: public keys (which may be known to others), and private keys (which may never be known by any except the owner). The generation of such key pairs depends on cryptographic algorithms which are based on mathematical problems termed one-way functions. Effective security requires keeping the private key private; the public key can be openly distributed without compromising security.[1]

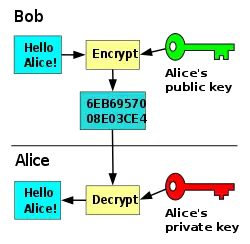

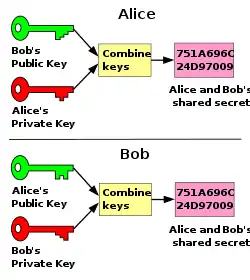

In such a system, any person can encrypt a message using the intended receiver's public key, but that encrypted message can only be decrypted with the receiver's private key. This allows, for instance, a server program to generate a cryptographic key intended for a suitable symmetric-key cryptography, then to use a client's openly-shared public key to encrypt that newly-generated symmetric key. The server can then send this encrypted symmetric key over an insecure channel to the client; only the client can decrypt it using the client's private key (which pairs with the public key used by the server to encrypt the message). With the client and server both having the same symmetric key, they can safely use symmetric key encryption (likely much faster) to communicate over otherwise-insecure channels. This scheme has the advantage of not having to manually pre-share symmetric keys (a fundamentally difficult problem) while gaining the higher data throughput advantage of symmetric-key cryptography.

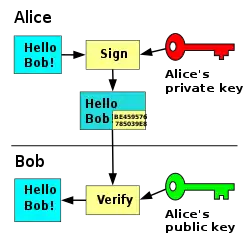

With public-key cryptography, robust authentication is also possible. A sender can combine a message with a private key to create a short digital signature on the message. Anyone with the sender's corresponding public key can combine that message with a claimed digital signature; if the signature matches the message, the origin of the message is verified (i.e., it must have been made by the owner of the corresponding private key).[2][3]

Public key algorithms are fundamental security primitives in modern cryptosystems, including applications and protocols which offer assurance of the confidentiality, authenticity and non-repudiability of electronic communications and data storage. They underpin numerous Internet standards, such as Transport Layer Security (TLS), S/MIME, PGP, and GPG. Some public key algorithms provide key distribution and secrecy (e.g., Diffie–Hellman key exchange), some provide digital signatures (e.g., Digital Signature Algorithm), and some provide both (e.g., RSA). Compared to symmetric encryption, asymmetric encryption is rather slower than good symmetric encryption, too slow for many purposes. Today's cryptosystems (such as TLS, Secure Shell) use both symmetric encryption and asymmetric encryption.

Description

Before the mid-1970s, all cipher systems used symmetric key algorithms, in which the same cryptographic key is used with the underlying algorithm by both the sender and the recipient, who must both keep it secret. Of necessity, the key in every such system had to be exchanged between the communicating parties in some secure way prior to any use of the system – for instance, via a secure channel. This requirement is never trivial and very rapidly becomes unmanageable as the number of participants increases, or when secure channels aren't available, or when, (as is sensible cryptographic practice), keys are frequently changed. In particular, if messages are meant to be secure from other users, a separate key is required for each possible pair of users.

By contrast, in a public key system, the public keys can be disseminated widely and openly, and only the corresponding private keys need be kept secret by its owner.

Two of the best-known uses of public key cryptography are:

- Public key encryption, in which a message is encrypted with a recipient's public key. For properly chosen and used algorithms, messages cannot in practice be decrypted by anyone who does not possess the matching private key, who is thus presumed to be the owner of that key and so the person associated with the public key. This can be used to ensure confidentiality of a message.

- Digital signatures, in which a message is signed with the sender's private key and can be verified by anyone who has access to the sender's public key. This verification proves that the sender had access to the private key, and therefore is very likely to be the person associated with the public key. This also ensures that the message has not been tampered with, as a signature is mathematically bound to the message it originally was made from, and verification will fail for practically any other message, no matter how similar to the original message.

One important issue is confidence/proof that a particular public key is authentic, i.e. that it is correct and belongs to the person or entity claimed, and has not been tampered with or replaced by some (perhaps malicious) third party. There are several possible approaches, including:

A public key infrastructure (PKI), in which one or more third parties – known as certificate authorities – certify ownership of key pairs. TLS relies upon this. This implies that the PKI system (software, hardware, and management) is trust-able by all involved.

A "web of trust" which decentralizes authentication by using individual endorsements of links between a user and the public key belonging to that user. PGP uses this approach, in addition to lookup in the domain name system (DNS). The DKIM system for digitally signing emails also uses this approach.

Applications

The most obvious application of a public key encryption system is for encrypting communication to provide confidentiality – a message that a sender encrypts using the recipient's public key which can be decrypted only by the recipient's paired private key.

Another application in public key cryptography is the digital signature. Digital signature schemes can be used for sender authentication.

Non-repudiation systems use digital signatures to ensure that one party cannot successfully dispute its authorship of a document or communication.

Further applications built on this foundation include: digital cash, password-authenticated key agreement, time-stamping services, non-repudiation protocols, etc.

Hybrid Cryptosystems

Because asymmetric key algorithms are nearly always much more computationally intensive than symmetric ones, it is common to use a public/private asymmetric key-exchange algorithm to encrypt and exchange a symmetric key, which is then used by symmetric-key cryptography to transmit data using the now-shared symmetric key for a symmetric key encryption algorithm. PGP, SSH, and the SSL/TLS family of schemes use this procedure; they are thus called hybrid cryptosystems. The initial asymmetric cryptography-based key exchange to share a server-generated symmetric key from the server to client has the advantage of not requiring that a symmetric key be pre-shared manually, such as on printed paper or discs transported by a courtier, while providing the higher data throughput of symmetric key cryptography over asymmetric key cryptography for the remainder of the shared connection.

Weaknesses

As with all security-related systems, it is important to identify potential weaknesses. Aside from poor choice of an asymmetric key algorithm (there are few which are widely regarded as satisfactory) or too short a key length, the chief security risk is that the private key of a pair becomes known. All security of messages, authentication, etc, will then be lost.

Algorithms

All public key schemes are in theory susceptible to a "brute-force key search attack".[4] Such attacks are impractical, however, if the amount of computation needed to succeed – termed the "work factor" by Claude Shannon – is out of reach of all potential attackers. In many cases, the work factor can be increased by simply choosing a longer key. But other algorithms may inherently have much lower work factors, making resistance to a brute-force attack (eg, from longer keys) irrelevant. Some special and specific algorithms have been developed to aid in attacking some public key encryption algorithms – both RSA and ElGamal encryption have known attacks that are much faster than the brute-force approach.[5] None of these are sufficiently improved to be actually practical, however.

Major weaknesses have been found for several formerly promising asymmetric key algorithms. The "knapsack packing" algorithm was found to be insecure after the development of a new attack.[6] As with all cryptographic functions, public-key implementations may be vulnerable to side-channel attacks that exploit information leakage to simplify the search for a secret key. These are often independent of the algorithm being used. Research is underway to both discover, and to protect against, new attacks.

Alteration of public keys

Another potential security vulnerability in using asymmetric keys is the possibility of a "man-in-the-middle" attack, in which the communication of public keys is intercepted by a third party (the "man in the middle") and then modified to provide different public keys instead. Encrypted messages and responses must, in all instances, be intercepted, decrypted, and re-encrypted by the attacker using the correct public keys for the different communication segments so as to avoid suspicion.

A communication is said to be insecure where data is transmitted in a manner that allows for interception (also called "sniffing"). These terms refer to reading the sender's private data in its entirety. A communication is particularly unsafe when interceptions can't be prevented or monitored by the sender.[7]

A man-in-the-middle attack can be difficult to implement due to the complexities of modern security protocols. However, the task becomes simpler when a sender is using insecure media such as public networks, the Internet, or wireless communication. In these cases an attacker can compromise the communications infrastructure rather than the data itself. A hypothetical malicious staff member at an Internet Service Provider (ISP) might find a man-in-the-middle attack relatively straightforward. Capturing the public key would only require searching for the key as it gets sent through the ISP's communications hardware; in properly implemented asymmetric key schemes, this is not a significant risk.

In some advanced man-in-the-middle attacks, one side of the communication will see the original data while the other will receive a malicious variant. Asymmetric man-in-the-middle attacks can prevent users from realizing their connection is compromised. This remains so even when one user's data is known to be compromised because the data appears fine to the other user. This can lead to confusing disagreements between users such as "it must be on your end!" when neither user is at fault. Hence, man-in-the-middle attacks are only fully preventable when the communications infrastructure is physically controlled by one or both parties; such as via a wired route inside the sender's own building. In summation, public keys are easier to alter when the communications hardware used by a sender is controlled by an attacker.[8][9][10]

Public key infrastructure

One approach to prevent such attacks involves the use of a public key infrastructure (PKI); a set of roles, policies, and procedures needed to create, manage, distribute, use, store and revoke digital certificates and manage public-key encryption. However, this has potential weaknesses.

For example, the certificate authority issuing the certificate must be trusted by all participating parties to have properly checked the identity of the key-holder, to have ensured the correctness of the public key when it issues a certificate, to be secure from computer piracy, and to have made arrangements with all participants to check all their certificates before protected communications can begin. Web browsers, for instance, are supplied with a long list of "self-signed identity certificates" from PKI providers – these are used to check the bona fides of the certificate authority and then, in a second step, the certificates of potential communicators. An attacker who could subvert one of those certificate authorities into issuing a certificate for a bogus public key could then mount a "man-in-the-middle" attack as easily as if the certificate scheme were not used at all. In an alternative scenario rarely discussed , an attacker who penetrates an authority's servers and obtains its store of certificates and keys (public and private) would be able to spoof, masquerade, decrypt, and forge transactions without limit.

Despite its theoretical and potential problems, this approach is widely used. Examples include TLS and its predecessor SSL, which are commonly used to provide security for web browser transactions (for example, to securely send credit card details to an online store).

Aside from the resistance to attack of a particular key pair, the security of the certification hierarchy must be considered when deploying public key systems. Some certificate authority – usually a purpose-built program running on a server computer – vouches for the identities assigned to specific private keys by producing a digital certificate. Public key digital certificates are typically valid for several years at a time, so the associated private keys must be held securely over that time. When a private key used for certificate creation higher in the PKI server hierarchy is compromised, or accidentally disclosed, then a "man-in-the-middle attack" is possible, making any subordinate certificate wholly insecure.

Examples

Examples of well-regarded asymmetric key techniques for varied purposes include:

- Diffie–Hellman key exchange protocol

- DSS (Digital Signature Standard), which incorporates the Digital Signature Algorithm

- ElGamal

- Elliptic-curve cryptography

- Various password-authenticated key agreement techniques

- Paillier cryptosystem

- RSA encryption algorithm (PKCS#1)

- Cramer–Shoup cryptosystem

- YAK authenticated key agreement protocol

Examples of asymmetric key algorithms not yet widely adopted include:

- NTRUEncrypt cryptosystem

- McEliece cryptosystem

Examples of notable – yet insecure – asymmetric key algorithms include:

Examples of protocols using asymmetric key algorithms include:

- S/MIME

- GPG, an implementation of OpenPGP, and an Internet Standard

- EMV, EMV Certificate Authority

- IPsec

- PGP

- ZRTP, a secure VoIP protocol

- Transport Layer Security standardized by IETF and its predecessor Secure Socket Layer

- SILC

- SSH

- Bitcoin

- Off-the-Record Messaging

History

During the early history of cryptography, two parties would rely upon a key that they would exchange by means of a secure, but non-cryptographic, method such as a face-to-face meeting, or a trusted courier. This key, which both parties must then keep absolutely secret, could then be used to exchange encrypted messages. A number of significant practical difficulties arise with this approach to distributing keys.

Anticipation

In his 1874 book The Principles of Science, William Stanley Jevons[11] wrote:

Can the reader say what two numbers multiplied together will produce the number 8616460799?[12] I think it unlikely that anyone but myself will ever know.[13]

Here he described the relationship of one-way functions to cryptography, and went on to discuss specifically the factorization problem used to create a trapdoor function. In July 1996, mathematician Solomon W. Golomb said: "Jevons anticipated a key feature of the RSA Algorithm for public key cryptography, although he certainly did not invent the concept of public key cryptography."[14]

Classified discovery

In 1970, James H. Ellis, a British cryptographer at the UK Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), conceived of the possibility of "non-secret encryption", (now called public key cryptography), but could see no way to implement it.[15] In 1973, his colleague Clifford Cocks implemented what has become known as the RSA encryption algorithm, giving a practical method of "non-secret encryption", and in 1974 another GCHQ mathematician and cryptographer, Malcolm J. Williamson, developed what is now known as Diffie–Hellman key exchange. The scheme was also passed to the USA's National Security Agency.[16] Both organisations had a military focus and only limited computing power was available in any case; the potential of public key cryptography remained unrealised by either organization:

I judged it most important for military use ... if you can share your key rapidly and electronically, you have a major advantage over your opponent. Only at the end of the evolution from Berners-Lee designing an open internet architecture for CERN, its adaptation and adoption for the Arpanet ... did public key cryptography realise its full potential.

These discoveries were not publicly acknowledged for 27 years, until the research was declassified by the British government in 1997.[17]

Public discovery

In 1976, an asymmetric key cryptosystem was published by Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman who, influenced by Ralph Merkle's work on public key distribution, disclosed a method of public key agreement. This method of key exchange, which uses exponentiation in a finite field, came to be known as Diffie–Hellman key exchange.[18] This was the first published practical method for establishing a shared secret-key over an authenticated (but not confidential) communications channel without using a prior shared secret. Merkle's "public key-agreement technique" became known as Merkle's Puzzles, and was invented in 1974 and only published in 1978.

In 1977, a generalization of Cocks' scheme was independently invented by Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir and Leonard Adleman, all then at MIT. The latter authors published their work in 1978 in Martin Gardner's Scientific American column, and the algorithm came to be known as RSA, from their initials.[19] RSA uses exponentiation modulo a product of two very large primes, to encrypt and decrypt, performing both public key encryption and public key digital signatures. Its security is connected to the extreme difficulty of factoring large integers, a problem for which there is no known efficient general technique (though prime factorization may be obtained through brute-force attacks; this grows much more difficult the larger the prime factors are). A description of the algorithm was published in the Mathematical Games column in the August 1977 issue of Scientific American.[20]

Since the 1970s, a large number and variety of encryption, digital signature, key agreement, and other techniques have been developed, including the Rabin cryptosystem, ElGamal encryption, DSA - and elliptic curve cryptography.

See also

- Books on cryptography

- GNU Privacy Guard

- ID-based encryption (IBE)

- Key escrow

- Key-agreement protocol

- PGP word list

- Pretty Good Privacy

- Pseudonymity

- Public key fingerprint

- Public key infrastructure (PKI)

- Quantum computing

- Quantum cryptography

- Secure Shell (SSH)

- Transport Layer Security (TLS)

- Symmetric-key algorithm

- Threshold cryptosystem

- Web of trust

Notes

- Stallings, William (3 May 1990). Cryptography and Network Security: Principles and Practice. Prentice Hall. p. 165. ISBN 9780138690175.

- Alfred J. Menezes, Paul C. van Oorschot, and Scott A. Vanstone (October 1996). "11: Digital Signatures" (PDF). Handbook of Applied Cryptography. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-8523-7. Retrieved 14 November 2016.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Daniel J. Bernstein (1 May 2008). "Protecting communications against forgery" (PDF). Algorithmic Number Theory. 44. MSRI Publications. §5: Public-key signatures, pp. 543–545. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- Paar, Christof; Pelzl, Jan; Preneel, Bart (2010). Understanding Cryptography: A Textbook for Students and Practitioners. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-04100-6.

- Mavroeidis, Vasileios, and Kamer Vishi, "The Impact of Quantum Computing on Present Cryptography", International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 31 March 2018

- Shamir, Adi; Shamir, Adi; Shamir, Adi (November 1982). "A polynomial time algorithm for breaking the basic Merkle-Hellman cryptosystem". 23rd Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (SFCS 1982): 145–152. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1982.5. Missing

|author2=(help) - Tunggal, Abi (20 February 2020). "What Is a Man-in-the-Middle Attack and How Can It Be Prevented - What is the difference between a man-in-the-middle attack and sniffing?". UpGuard. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Tunggal, Abi (20 February 2020). "What Is a Man-in-the-Middle Attack and How Can It Be Prevented - Where do man-in-the-middle attacks happen?". UpGuard. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- martin (30 January 2013). "China, GitHub and the man-in-the-middle". GreatFire. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- percy (4 September 2014). "Authorities launch man-in-the-middle attack on Google". GreatFire. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Jevons, William Stanley, The Principles of Science: A Treatise on Logic and Scientific Method p. 141, Macmillan & Co., London, 1874, 2nd ed. 1877, 3rd ed. 1879. Reprinted with a foreword by Ernst Nagel, Dover Publications, New York, NY, 1958.

- This came to be known as "Jevons's number". The only nontrivial factor pair is 89681 × 96079.

- Principles of Science, Macmillan & Co., 1874, p. 141.

- Golob, Solomon W. (1996). "On Factoring Jevons' Number". Cryptologia. 20 (3): 243. doi:10.1080/0161-119691884933. S2CID 205488749.

- Sawer, Patrick (11 March 2016). "The unsung genius who secured Britain's computer defences and paved the way for safe online shopping". The Telegraph.

- Tom Espiner (26 October 2010). "GCHQ pioneers on birth of public key crypto". www.zdnet.com.

- Singh, Simon (1999). The Code Book. Doubleday. pp. 279–292.

- Diffie, Whitfield; Hellman, Martin E. (November 1976). "New Directions in Cryptography" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 22 (6): 644–654. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.37.9720. doi:10.1109/TIT.1976.1055638. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2014.

- Rivest, R.; Shamir, A.; Adleman, L. (February 1978). "A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-Key Cryptosystems" (PDF). Communications of the ACM. 21 (2): 120–126. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.607.2677. doi:10.1145/359340.359342. S2CID 2873616.

- Robinson, Sara (June 2003). "Still Guarding Secrets after Years of Attacks, RSA Earns Accolades for its Founders" (PDF). SIAM News. 36 (5).

References

- Hirsch, Frederick J. "SSL/TLS Strong Encryption: An Introduction". Apache HTTP Server. Retrieved 17 April 2013.. The first two sections contain a very good introduction to public-key cryptography.

- Ferguson, Niels; Schneier, Bruce (2003). Practical Cryptography. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-22357-3.

- Katz, Jon; Lindell, Y. (2007). Introduction to Modern Cryptography. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-58488-551-1.

- Menezes, A. J.; van Oorschot, P. C.; Vanstone, Scott A. (1997). Handbook of Applied Cryptography. ISBN 0-8493-8523-7.

- IEEE 1363: Standard Specifications for Public-Key Cryptography

- Christof Paar, Jan Pelzl, "Introduction to Public-Key Cryptography", Chapter 6 of "Understanding Cryptography, A Textbook for Students and Practitioners". (companion web site contains online cryptography course that covers public-key cryptography), Springer, 2009.

External links

- Oral history interview with Martin Hellman, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Leading cryptography scholar Martin Hellman discusses the circumstances and fundamental insights of his invention of public key cryptography with collaborators Whitfield Diffie and Ralph Merkle at Stanford University in the mid-1970s.

- An account of how GCHQ kept their invention of PKE secret until 1997