Qajar art

Qajar art (Persian: هنر دوره قاجاریه) refers to the art, architecture, and art-forms of the Qajar dynasty of the late Persian Empire, which lasted from 1781 to 1925 in Iran (Persia).

.jpg.webp)

._Portrait_of_Fath_'Ali_Shah_Qajar%252C_1815.jpg.webp)

The boom in artistic expression that occurred during the Qajar era was the fortunate side effect of the period of relative peace that accompanied the rule of Agha Muhammad Khan and his descendants. With his ascension, the bloody turmoil that had been the 18th century in Persia came to a close, and made it possible for the peacetime arts to again flourish.

Qajar painting

Most notably, Qajar art is recognizable for its distinctive style of portraiture.

Origins and influences

The roots of traditional Qajar painting can be found in the style of painting that arose during the preceding Safavid empire. During this time, there was a great deal of European influence on Persian culture, especially in the arts of the royalty and noble classes. European art was undergoing a period of realism and this can be seen in the depiction of objects especially by Qajar artists. The European influence is very well evidenced in the preëminent position and prestige of oil painting. While oil paintings had been par for the course during previous periods of Persian art, it was the influence of the European masters, like Rubens and Rembrandt, the true masters of oil portraiture, that raised it to the highest level. Heavy application of paint and dark, rich, saturated colors are elements of Qajar painting that owe their influences directly to the European style.

Development of painting style

While the depiction of inanimate objects and still lifes is seen to be very realistic in Qajar painting, the depiction of human beings is decidedly idealised. This is especially evident in the portrayal of Qajar royalty, where the subjects of the paintings are very formulaically placed and situated to achieve a desired effect.

Royal portraiture

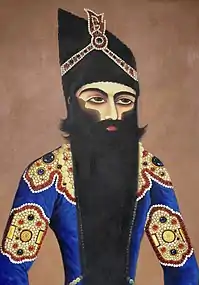

Most famous of the Qajar artworks are the portraits that were made of the various Persian Shahs. Each ruler, and many of their sons and other relatives, commissioned official portraits of themselves either for private use or public display. The most famous of these are of course the myriad portraits which were painted of Fath Ali Shah Qajar, who, with his narrow waist, long black bifurcated beard and deepest eyes, has come to exemplify the Romantic image of the great Oriental Ruler. Many of these paintings were by the artist Mihr 'Ali. While the portraits were executed at various points throughout the life of the Shah, they adhere to a canon in which the distinctive features of the ruler are emphasized. Portraits exist of Fath Ali Shah in a very wide assortment of situations, from the armor-clad warrior king to the flower smelling gentleman, but all are similar in their depiction of the Shah, differing only slightly, usually due to the specific artist of the portrait. It is only appropriate that this particular Shah be so immortalized in this style, as it was under his rule as the second Qajar shah that the style truly flourished. One reason for this were the stronger and stronger diplomatic ties that the Qajar rulers were nurturing with European powers.

As the Shangri La Center for Islamic Arts and Culture notes, "Later Iranian art of the Afsharid (1736–96), Zand (1750–94) and Qajar (1779–1924) periods is distinguished by the depiction of life-size figures, whether in stone relief, tilework or painting on canvas. In the latter category, Qajar rulers like Fath ‘Ali Shah (r. 1797–1834) perpetuated a widespread interest in large-scale portraiture (even sending portraits to political rivals)."[1]

While Fath Ali Shah himself never visited Europe, many portraits of him were sent with envoys in the effort to convey the imperial majesty of the Persian court. With the rise of Naseraddin Shah photography became much more important in the art of the period, and portraiture, while still used for official purposes, fell gradually out of favor. In addition, as Nassirudin Shah was the first Persian ruler to visit Europe, the official sending of portraits was left by the wayside, a relic of times gone by.

Other portraiture

The depiction of nonroyal persons also has a very important place in the explanation and understanding of Qajar art. While naturally not commoners, the subjects of these portraits were often minor princes (of which there were many!), the grandsons, nephews, and great-nephews of the ruling or previously ruling Shahs. These princes, with the wealth and position of their families, had very little else to do but contribute to the arts, so their patronage was certainly less than detrimental to the arts of the time. Often, portraits of this class would be commissioned as depictions of family groups, depicting the male, an idealized, nubile wife, and their perfectly formed child. Other times, they would be in the form of a royal portrait, depicting solely the male commissioner, but with subtle variations making it clear that the sitter is not a Royal. One way that this was accomplished was through a cartouche that was displayed next to the head of each portrait's subject, clarifying who was being depicted, and any relevant titles (such as Soltān, shāhzādeh, &c.). For the ruling head of Persia, this cartouche is fairly regulated, ("al-soltān Official name Shāh Qājār"), while for anyone else, it may include a longer name, a lesser title or a short genealogy.

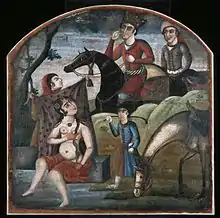

Depiction of women

Gender was often blurred in early Qajar Iran paintings, displaying similarities in body and facial features between men and women who were illustrated to be beautiful in many paintings. Young males and females were often linked to the object of desire. The appearance of young beardless men were called mukhannas.[2] It was not until the 19th century when females were depicted as more individualized with distinct feminine facial and body features which ultimately led to the disappearance of the mukhanna, the male object of desire.[3] 19th century Qajar art also brought the emergence of the bare breasted woman. Examples of the bare breast would be seen through a dress for fetishistic pleasure and becomes a major theme in Qajar paintings. These bare breasted women were portrayed as angels, European women, or women of pleasure such as acrobats or musicians. Some paintings include a portrayal of Mary and baby Jesus. Eventually, the bare breast led to an indication of womanhood.[4]

The posture and positions women were placed in these paintings helps tell a story. Women often held objects such as mirrors, fruit, or wine to represent beauty and pleasure. These representations go in hand with Persian poetry.[5] With Persian literature in mind, occasional paintings featured women with an "outward gaze" which represents "directly addressing the reader"[6] and is seen in many narrative paintings from Shirin and Khusraw, Yusuf and Zulaykha, and Shaykh San'an. In contrast to traditional postures and positions of women in 19th century Qajar art, was a common female representation of women gracefully upside down on their hands on a knife. This was interpreted as rejection to social order which is represented in folk narratives in both pictorial and literary representations to dismiss the stereotype of passive Iranian women.[7]

Calligraphy in the Qajar era

Calligraphy is and has been the definitive Persian art form. There exists a prohibition in Islam against the depiction of human beings, similar to the Jewish rule against graven images, and as such, calligraphy and its associated art forms became a very important part of Islamic expression. Upon the introduction of the Arabic script to Persia, the people therein set themselves to making it their own.

The Shāhanshāhnāmeh

During the reign of Fath Ali Shah Qajar, a work of literature and art was commissioned that was intended to rival the work of Ferdowsi. This book was called the Shāhanshāhnāmeh (شاهنشاهنامه, lit. "Book of the King of Kings"). It is apparent to the scholar of Persian art and literature that this book is based upon the work of art known as the Shāhnāmeh (شاهنامه, lit. "Book of Kings") which was written by Ferdowsi in the year 1000 . The Shahnameh, in brief, chronicles the quasi-mythical founding of the Persian Empire and the heroes and villains who punctuated its inception. This Sahanshahnameh is now situated in the National Library of Vienna, Austria.

Qajar textile arts

The sartorial inclinations of the Qajar period were not so very different from those of earlier period until the latter half of the era. As is evidenced by the early portraiture of Fath Ali Shah Qajar and Mohammad Shah Qajar, the traditional styles of dress in Persia were preserved, but as Western influences became more and more prevalent, the royal portraits began to depict the Shah in a more Western, military style garb (such as the portrait of Nassirudin Shah Qajar above). This is not to say, however, that the traditional textile arts of Persia had fallen into disuse. While the Shah wished to appear advanced and western to European monarchs and diplomats, it was still his duty to exude the pride and ancient glory of the Persian Empire, so court dress retained very strong elements of traditional dress.

Qajar architecture

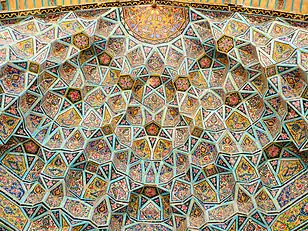

Examples of Qajar era architecture and landscape design Include:

- Constitution House – Tabriz

- Nasir al-Mulk Mosque – Shiraz.

- Golestan Palace Complex – Tehran.

- The Shams-ol-Emareh Palace (1860s) – first iron (steel) building in the city.

- The Niavaran Palace Complex – Tehran.

- The Sahebqraniyeh Palace

- The Kushk of Ahmad Shah pavilion

- Sa'dabad Palace Complex – Tehran.

- The Green Palace

- Eram Garden (Bāgh-e Eram) Persian gardens – Shiraz.

- Shazdeh Garden (1890s) – Kerman.

- Abbas Mirza Mosque – Yerevan (largely destroyed nowadays)

Qajar photography

Many new technologies were adopted under the rule of Nasir al-Din Shah (ruled 1848 to 1896). Photography became popular in Iran during the late Qajar period and was embraced enthusiastically by Nasir al-Din Shah, who famously photographed many of the women of the Qajar palace. During the period of his rule, the interaction between photography and painting grew, both in terms of style and composition.[8]

in 1840s daguerreotype were introduced to Persia and paved the way for more photographic instruments to be introduced to Persia. Unlike the Ottoman Empire, where photography was seen as sinful, in Persia it was accepted and largely used. The only surviving daguerreotype photograph is a self-portrait by Prince Malek Qasem Mirza, Naser al-din Shah's uncle. [9]

In 1889, the first essay on photography in Iran entitled Aksiyeh Hashariyeh was written by Mohammad ibn-Ali Meshkat al-Molk. [10]

Gallery

- Qajar art

Qajari wall painting at Qavam House—Narenjestan e Qavam.

Qajari wall painting at Qavam House—Narenjestan e Qavam. Muqarna at the Nasir al-Mulk Mosque.

Muqarna at the Nasir al-Mulk Mosque. Qavam—Ghavam House facade and balcony.

Qavam—Ghavam House facade and balcony..jpg.webp) Qavam House

Qavam House "Kushk of Ahmad Shah" at the Niavaran Palace Complex.

"Kushk of Ahmad Shah" at the Niavaran Palace Complex..jpg.webp) Boy Holding a Falcon, Qajar Dynasty

Boy Holding a Falcon, Qajar Dynasty Eram garden

Eram garden Tiles painted with polychrome glazes over a white glaze.

Tiles painted with polychrome glazes over a white glaze..jpg.webp) Beglyar Afshar. Portrait of Jamshid Ed-Dovle

Beglyar Afshar. Portrait of Jamshid Ed-Dovle Painted tiles with design of birds, hunting and flowers from Qajar dynasty

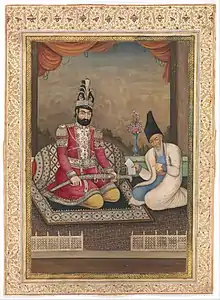

Painted tiles with design of birds, hunting and flowers from Qajar dynasty Portrait of Muhammad Shah Qajar and his Vizier Haj Mirza Aghasi, second quarter of the nineteenth century, Ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, Iran, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[11]

Portrait of Muhammad Shah Qajar and his Vizier Haj Mirza Aghasi, second quarter of the nineteenth century, Ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, Iran, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[11]

See also

- Royal Persian Painting in Qajar era

- Malik National Museum of Iran

- Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran

- Shangri La (Doris Duke)

- Esmail Jalayer

References

- "Doris Duke's Shangri La | Painting". www.shangrilahawaii.org. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- Najmabadi, Afsaneh (2005). Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iran Modernity. University of California Press. p. 16.

- Najmabadi, Afsaneh (2005). Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iran Modernity. University of California Press. p. 26.

- Najmabadi, Afsaneh (2005). Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iran Modernity. University of California Press. p. 39.

- Vanzan, Anna (2014). "The Popularization of Art in Late Qajar Iran: The Importance of Class and Gender". Quaderni Asiatici: 146.

- Najmabadi, Afsaneh (2005). Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iran Modernity. University of California Press. p. 30.

- Vanzan, Anna (2014). "The Popularization of Art in Late Qajar Iran: The Importance of Class and Gender". Quaderni Asiatici: 150.

- http://www.mia.org.qa/en/qajar-women/qajar-photography

- http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/daguerreotype

- https://en.mehrnews.com/news/7801/Iranian-portrait-photography-developed-during-Qajar-era

- "Portrait of Muhammad Shah Qajar and his Vizier Haj Mirza Aghasi".

- Diba, Layla S., with Maryam Ekhtiar. Royal Persian Painting: The Qajar Epoch, 1785–1925. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum of Art with I.B. Tauris, 1998.

- Raby, Julian. Qajar Portraits : Figure Paintings from Nineteenth Century Persia. Brooklyn, NY: I.B. Tauris, 1999.

- Loukonine, Vladimir. Lost Treasures of Persia: Persian Art in the Hermitage Museum. Mage Publishers. 1996.

- Ritter, Markus. Moscheen und Madrasabauten in Iran 1785-1848: Architektur zwischen Rückgriff und Neuerung (Mosque and Madrasa Buildings in Iran 1785-1848: Architecture between re-adaptation and innovation). German, English summary. Brill Publishers: Leiden and Boston, 2005.

- Uzun, Tolga. "Qajar Portrait Art In The Second Half Of The 19th Century: The Portraits Of Nasir Al-Din Shah", Ph.D. Thesis - Department of Art History- Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey 2005.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qajar art. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qajar architecture. |

| Iranian art |

|---|

| Visual arts |

| Decorative arts |

| Literature |

| Performance arts |

| Other |

Shangri La Center for Islamic Arts and Cultures, "Qajar Art"