Radar picket

A radar picket is a radar-equipped station, ship, submarine, aircraft, or vehicle used to increase the radar detection range around a nation or force to protect it from surprise attack, typically air attack. By definition a radar picket must be some distance removed from the anticipated targets to be capable of providing early warning. Often several detached radar units encircle a target to provide increased cover in all directions; another approach is to position units to form a barrier line.

Radar picket units may also be equipped to direct friendly aircraft to intercept any possible enemy. In British terminology the radar picket function is called aircraft direction. Airborne radar pickets are generally referred to as airborne early warning.

US Navy World War II radar pickets

Radar picket ships first came into being in the US Navy during World War II to aid in the Allied advance to Japan. The number of radar pickets was increased significantly after the first major employment of kamikaze aircraft by the Japanese in the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944. Fletcher- and Sumner-class destroyers were pressed into service with few modifications at first. Later, additional radars and fighter direction equipment were fitted, along with more light anti-aircraft (AA) guns for self-defense, usually sacrificing torpedo tubes to make room for the new equipment, particularly the large height-finding radars of the era. Deploying some distance from the force to be protected along likely directions of attack, radar pickets were the nearest ships to the Japanese airfields. Thus, they were usually the first vessels seen by incoming waves of kamikazes, and were often heavily attacked.[1]

_underway_c1958.jpeg.webp)

The radar picket system saw its ultimate development in World War II in the Battle of Okinawa. A ring of 15 radar picket stations was established around Okinawa to cover all possible approaches to the island and the attacking fleet. Initially, a typical picket station had one or two destroyers supported by two landing ships, usually landing craft support (large) (LCS(L)) or landing ship medium (rocket) (LSM(R)), for additional AA firepower. Eventually, the number of destroyers and supporting ships were doubled at the most threatened stations, and combat air patrols were provided as well. In early 1945, 26 new construction Gearing-class destroyers were ordered as radar pickets without torpedo tubes, to allow for extra radar and AA equipment, but only some of these were ready in time to serve off Okinawa. Seven destroyer escorts were also completed as radar pickets.

The radar picket mission was vital, but it was also costly to the ships performing it. Out of 101 destroyers assigned to radar picket stations, 10 were sunk and 32 were damaged by kamikaze attacks. The 88 LCS(L)s assigned to picket stations had two sunk and 11 damaged by kamikazes, while the 11 LSM(R)s had three sunk and two damaged.[2][3]

The high casualties off Okinawa gave rise to the radar picket submarine, which had the option of diving when under attack. It was planned to employ converted radar picket submarines should the invasion of Japan become necessary. Two submarines (Grouper and Finback) received rudimentary radar conversions during the war,[4] and two others (Threadfin and Remora) were completed immediately after the war with the same suite, but none were used postwar in this role.[5]

German and Japanese WWII radar pickets

From 1943 Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine operated several radar-equipped night fighter guide ships (Nachtjagdleitschiffe), including NJL Togo. which was equipped with a FuMG A1 Freya radar for early warning and a Würzburg-Riese gun laying radar, plus night fighter communications equipment. From October 1943, the NJL Togo cruised the Baltic Sea under the operational control of the Luftwaffe. In March 1944, after the three great Soviet bombing raids on Helsinki, she arrived in the Gulf of Finland to provide night fighter cover for Tallinn and Helsinki. Also, the Imperial Japanese Navy briefly modified two Ha-101 class submarines as dedicated radar pickets in the first half of 1945, but reconverted them to an even more important role as tanker submarines in June of that year.

Cold War

During the Cold War, the Royal Canadian Air Force and the United States Air Force jointly built and operated radar picket stations to detect Soviet bombers, and the United States Navy expanded the naval radar picket concept. The wartime radar picket destroyers (DDR) were retained, and additional DDRs, destroyer escorts (DER), submarines (SSR, SSRN), and auxiliaries (AGR) were converted and built 1946–1959. The naval concepts were: 1) every carrier group would have radar pickets deployed around it for early warning of the increasing threat of Soviet air-to-surface missile attack, and 2) radar pickets would form barriers off the North American coasts, thus extending the land based lines. While on station, all of these assets - other than those assigned to fleet defense - were operationally controlled by the Aerospace Defense Command and after May 1958 NORAD.

Fixed installations

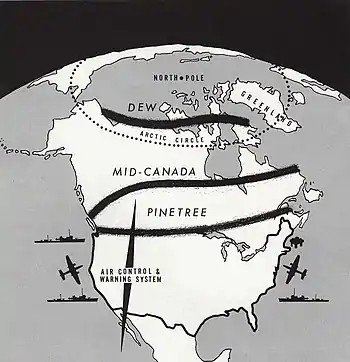

During the 1950s the governments of Canada, Denmark, and the United States built three lines of fixed radar picket sites across Canada, and with the DEW Line into Alaska and Greenland. These were the Pinetree Line (1951), the Mid-Canada Line (1956), and the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line (1957). There was also a line of radar sites in Alaska extending westward from the end of the DEW Line to the end of the Aleutian Islands, and a line eastward from the Greenland end of the DEW Line to Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Scotland.

There were also three oil-rig-type offshore radar stations known as "Texas Towers" off the New England coast.

Destroyer Escort conversions

_off_Newfoundland%252C_in_March_1957.jpg.webp)

The 26 wartime Gearing-class DDRs were supplemented by nine additional conversions during the early 1950s. The seven wartime DERs were not considered worth modernizing and were relegated to secondary roles, so 36 additional DER conversions were performed in 1951 through 1958:

- Six diesel powered Edsall class DEs were converted into DERs in 1951 and 1952 under project SCB 46: converted were Fessenden, Harveson, Joyce, Kirkpatrick, Otterstetter, and Strickland.[6]

- Two DEs which were unfinished at the end of World War II, Vandivier and Wagner, were completed as DERs in 1954 under SCB 46A. As John C. Butler-class DEs they had steam powerplants and so lacked the endurance of their diesel half sisters. This was an experiment intended to validate the conversion should the design be required for any future mobilization. These two ships would be the first DERs to be retired.[7]

- Another 28 Edsall-class DEs would be converted into DERs from 1954 through 1957 under SCB 46B.[8]

The DERs were used in 1955–1965 to form two Barrier Forces known as BarLant and BarPac, which extended the DEW Line from Argentia, Newfoundland to the Azores in the Atlantic, and from Adak, Alaska to Midway in the Pacific.[9]

Converted merchant ships

.jpg.webp)

From 1955 to 1965 the United States Navy employed Guardian-class radar picket ships (converted under SCB 126 from the former boxed aircraft transport version of the Liberty ship) to create barrier lines off the East and West Coasts. Eight were homeported at Treasure Island, California and eight at Davisville, Rhode Island. The ships' names matched the mission: USS Guardian (AGR -1), USS Lookout (AGR-2), USS Skywatcher (AGR-3), USS Searcher (AGR-4), USS Investigator (AGR-9), USS Outpost (AGR-10), USS Protector (AGR-11), and USS Vigil (AGR-12) on the East Coast and USS Scanner (AGR-5), USS Locator (AGR-6), USS Picket (AGR-7), USS Interceptor (AGR-8), USS Interdictor (AGR-13), USS Interpreter (AGR-14), USS Tracer (AGR-15) and USS Watchman (AGR-16) on the West Coast. The hull classification symbol of the ships was initially YAGR, changed to AGR in 1958. The standard crew consisted of 13 officers, eight chief petty officers, and 125 enlisted.[10]

Picket stations were about 400–500 miles off each coast and provided an overlapping radar or electronic barrier against approaching aircraft. Typical station duty was about 30–45 days out and 15 days in port. While on station, each ship stayed within a specific radius of its assigned picket station, reporting and tracking all aircraft contacts. Each ship carried qualified air controllers to direct intercept aircraft sent out to engage contacts. While on station other duties such as search and rescue, weather reporting, and miscellaneous duties were assigned. The National Marine Fisheries Service even provided fishing gear so that the crew could fish for tuna during the season, and the ships sent daily reports of fish caught for research purposes.

Converted and purpose-built submarines

The U.S. Navy continued to develop radar picket submarines (SSRs) after World War II, and by 1953, a total of 10 SSR conversions had been performed:

- In 1946 submarine radar picket conversions were performed on Spinax and Requin under the Migraine I project; these were more extensive than the rudimentary conversions made a year earlier for the planned invasion of Japan. The radar equipment of these diesel submarines took the place of torpedoes in the stern torpedo rooms. The radar antennas were mounted directly on the hull above the equipment, where they suffered spray damage.[4]

- Migraine II (aka SCB 12) involved raising the antennas off the hull onto masts, moving the equipment to the aft battery room (higher capacity GUPPY batteries were installed forward to compensate), and adding topside fathometers to give a limited under-ice capability. The aft torpedo tubes were removed and the compartment used for berthing and storage. Burrfish and Tigrone were converted, and the two Migraine I submarines were also upgraded to this standard.[11]

- Migraine III (aka SCB 12A) had the most extensive conversion with an added 27.5-foot (8.4 m) compartment for an expanded combat information center (CIC). The search antenna was moved to an enlarged sail located over the new compartment. Converted were Pompon, Rasher, Raton, Ray, Redfin, and Rock.[12]

In 1956 two large, purpose-built diesel SSRs, the Sailfish class (designed under project SCB 84), were commissioned. These were designed for a high surface speed with the intent of scouting in advance of carrier groups. However, the SSRs did not fare well in this mission. Their maximum surfaced speed of 21 knots was too slow to effectively operate with a carrier group, although it was sufficient for amphibious group operations.

It was thought that nuclear power would solve this problem. The largest, most capable, and most expensive radar picket submarine was the nuclear-powered USS Triton (SSRN-586), designed under project SCB 132 and commissioned in 1959. The longest submarine built by the United States until the Ohio class Trident missile submarines of the 1980s, Triton's two reactors allowed her to exceed 30 knots on the surface.[13]

List of radar picket submarines

|

US Atlantic Fleet[13]

|

|

USS Tigrone (SSR-419) in radar picket configuration.

|

Replacement by aircraft

The first U.S. airborne early warning aircraft were the carrier based Grumman TBM-3W Avenger, followed by the Grumman AF-2W Guardian (not to be confused with the AGR ships of the same name) and the Douglas AD-3W, -4W, and -5W Skyraider; though the Guardians and Skyraiders were built in large numbers, none were very successful as they were too small to function as a full CIC, and all were used more often in the ASW role. The latter Sikorsky HR2S-1W helicopter also failed, largely due to excessive vibration, slow speed, and cost.[14]

Far more successful was the land based Lockheed EC-121 Warning Star, which was introduced in 1954 in both Air Force and Navy service as pickets and in other roles. As pickets the Air Force EC-121s provided radar coverage by flying "Contiguous Barrier" orbits 300 miles offshore, between the coasts and the AGR Guardian picket lines. The Navy version (designated WV-2 before 1962) flew over the BarLant and BarPac DER lines. Their main deficiency was lack of endurance, which made them unsuitable for naval fleet coverage.

Perhaps the most successful airborne radar pickets were the nine Goodyear ZPG-2W and ZPG-3W blimps: starting in 1955 they successfully combined airborne early warning radar surveillance and long endurance, but they were fragile, expensive, and too slow to quickly reach stations far from base. They were retired in 1962.[15]

The introduction of the Grumman WF-2 Tracer (later the E-1 Tracer) carrier-based airborne early warning aircraft in 1958 doomed the surface and submarine radar pickets as carrier escorts. Airborne radar had evolved to the point where it could warn of an incoming attack more efficiently than a surface ship. In 1961 the DDRs and SSRs were withdrawn. All but six DDRs received anti-submarine warfare conversions under the FRAM I and FRAM II programs and were redesignated as DDs; the remaining six were somewhat modernized under FRAM II and retained in the DDR role. The SSRs were converted to other roles or scrapped. Triton was left without a mission. Some alternatives were considered, including serving as an underwater national command post, but she eventually became the first US nuclear submarine to be decommissioned, in 1969.[13][16]

By 1965, the development of over-the-horizon radar made the barrier forces obsolete, and the DERs and the AGR Guardians were retired. The EC-121s would be allocated to other roles.

The final use of the radar picket concept by the US Navy was in the Vietnam War. The Gulf of Tonkin Positive Identification Radar Advisory Zone (PIRAZ) guided missile destroyer leaders (aka frigates) (redesignated as cruisers in 1975) and cruisers provided significant air control and air defense in that war.[17]

British Aircraft Direction Ships

The British Royal Navy constructed or converted two types of dedicated aircraft direction ships in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Four World War II Battle-class destroyers and four Weapon-class destroyers were converted 1959-1962 as Fast Air Detection Escorts to accompany fast carrier groups. Also, four Type 61 Salisbury-class frigates were commissioned 1957–1960 to accompany slow carrier or amphibious groups. However, the aircraft direction function was short-lived. With the mid-1960s decision to phase out the fast carriers, the Battle-class ships were placed in reserve 1966-1968 and were scrapped or converted to non-combat roles by 1974. The Salisbury-class were relegated to non-combat roles or sold by the end of 1978.

Soviet radar picket ships

Twenty T43-class minesweepers were converted to KVN-50 class radar picket ships between 1955 and 1959. Modifications involved replacing the aft gun turret with a Knife Rest-A or Big Net radar. Most were retired during the 1970s or relegated to training duties, with the last withdrawn in 1987.[18]

Four Whiskey-class submarines were converted to Project 640 radar picket boats between 1959 and 1963 by fitting a Boat Sail radar in an enlarged conning tower. These were known to NATO as "Whiskey Canvas Bag" from the canvas coverings often put over the radar when NATO aircraft approached. While the US radar picket submarines were intended for fleet defense, the Project 640 boats were intended to provide warning of air attacks on Soviet coastal territory.[19][20]:119

14 further T43-class minesweepers were converted to Project 258 KVN-6 class radar picket ships between 1973 and 1977 with Kaktus radars. Some were later modified to Project 258M ships with Rubka (NATO: Strut Curve) radars.[18]

Three T58-class minesweepers were converted to radar picket ships between 1975 and 1977 by replacing the aft 57 mm gun turret with a Knife Rest-B radar.[20]:198

Three other projects were cancelled before conversions were made.

- Project 959 - further conversions the T58-class minesweeper with upgraded radar

- Project 962 - a fourth cruiser type following on from the Kresta I, Kresta II and Kara design[21]

- Project 996 - conversion of a Sovremennyy-class destroyer

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guardian class radar picket ships. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle class destroyer. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salisbury class frigate. |

References

Notes

- Friedman, Destroyers, pp. 202-206

- Friedman, Destroyers, pp. 202-210, 230-233

- Review by William Gordon of Rielly, Robin L. "Kamikazes, Corsairs, and Picket Ships: Okinawa, 1945", Casemate Publishing, 2008 ISBN 1-93203-386-6.

- Friedman, Submarines, pp. 90

- Friedman, Submarines, pp. 253

- Friedman, Destroyers, pp 230-231

- Friedman, Destroyers, pp 231-232

- Friedman, Destroyers, pp 232

- Friedman, Destroyers, pp. 231-233

- YAGR Website Ship List

- Friedman, Submarines, pp. 91-93

- Friedman, Submarines, pp. 91-96

- Whitman, Edward C. (Winter–Spring 2002). "Cold War Curiosities: U.S. Radar Picket Submarines". Undersea Warfare. Retrieved 26 January 2014., Issue 14

- "S-56/HR2S-1/H-37 Helicopter". sikorskyarchives. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Sky Ships: A History of the Airship in the United States Navy, Althoff, W.F., Pacifica Press, c1991, ISBN 0-935553-32-0

- Friedman, Destroyers, p. 231-233

- Friedman, Destroyers, p. 227

- Jane's Weapon Systems 1988- 1989. Jane's Information Group. 1987. p. 618. ISBN 9780710608550.

- Norman Polmar and Kenneth J. Moore (2004). Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. Potomac Books. p. 27. ISBN 1574885944.

- Norman Polmar (1983). Guide to the Soviet navy. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870212397.

- Edward Hampshire (2017). Soviet Cold War Guided Missile Cruisers. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 1472817427.

Sources

- Battle Experience: Radar Pickets and Methods of Combating Suicide Attacks off Okinawa, 20 July 1945.

- dtic.mil definition of radar picket

- Friedman, Norman (2004). US Destroyers: An Illustrated Design History (Revised Edition). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-442-3.

- Friedman, Norman (1994). U.S. Submarines Since 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 1-55750-260-9.

- GUPPY, SSR, and other diesel boat conversions page

- Map of Okinawa picket stations in April 1945

- Review by William Gordon of Rielly, Robin L. Kamikazes, Corsairs, and Picket Ships: Okinawa, 1945, Casemate Publishing, 2008 ISBN 1-93203-386-6.

- USS Drexeler description of protection of Okinawa

- Whitman, Edward C. "Cold War Curiosities: U.S. Radar Picket Submarines", Undersea Warfare, Winter-Spring 2002, Issue 14

- YAGR Website Ship List