Radin Yeshiva

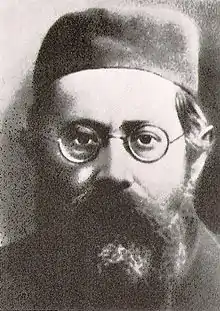

The Radin Yeshiva, originally located in Radun, Poland (now in Belarus), was established by Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan (known as the Chofetz Chaim after the title of his well-known sefer) in 1869. Because of its founder's nickname, the institution is often referred to as Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim of Radin. Its successors officially adopted this name.

Origins

In 1869 when the Chofetz Chaim returned from Vashilyshok to Raduń his first action was to establish a group to whom he could spread the knowledge of Torah. The founding of the yeshiva is mentioned in one of the letters of the Chofetz Chaim:

- "The beginning of the founding began from when I returned from the town of Vashilyshok...in the year 1869. Following my arrival in Raduń, the Almighty stirred my spirit to gather young students and scholars for the study of Torah..."

Although at the time Raduń was practically an isolated village, away from undesirable urban distractions and an ideal location for establishing a place of Torah study, living conditions were difficult. This meant that the chances of garnering enough local financial support to run a large and prosperous institution were low. This led the Chofetz Chaim to send some boys to other yeshivas, which also had better facilities, and keep the enrolment limited. The students of the yeshivas made do with sleeping on the benches in the study hall and were referred to as "perushim" because they separated themselves from worldly luxuries and immersed themselves in study of Torah. From the start meals weren't provided at the yeshiva and students were allocated to various homes in the village where they were given meals. It was when the Chofetz Chaim felt that this set up was not befitting of yeshiva students that he abolished the so-called "teg-essen" and went about arranging a house to house food collection. The collected food would then be distributed among the students. After some time a kitchen was opened by the wife of the Chofetz Chaim and she together with other women would collect provisions and cook meals which were served to the students in the yeshiva building.[1]

The yeshiva remained small in number until 1883 when the Chofetz Chaim took on his son-in-law Rabbi Hersh Levinson as an assistant to help carry the burden running the yeshiva. After his appointment, the yeshiva expanded and the conditions improved. In 1900 Rabbi Moshe Landynski, an alumnus of the Volozhin Yeshiva, was appointed rosh yeshiva. At later stages two other deans were in turn appointed: Rabbi Yitzchak Maltzon, who eventually settled in Jerusalem, and Rabbi Baruch Ish Alaksot, who later became a rosh yeshiva in Slabodka Yeshiva. Rabbi Eliezer Lufet also served as mashgiach ruchani for a short period.

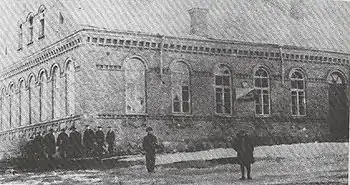

New yeshiva building

In 1904, after the influx of students, the local Beth midrash became too small to accommodate the yeshiva and a new building was constructed to house the college. However, as the years progressed, so did the student intake and with pupils now numbering in the hundreds, some were forced to study in the local synagogue. This set up was not favoured by the faculty who decided that a new, larger building, able to hold the entire student roll, was needed. And so it was, in 1912 that the original building was demolished to make way for a new edifice which would be big enough to contain all the students, which at the time exceeded 300. The Chofetz Chaim raised the 15,000 rubles necessary for the task and construction was finished in 1913. The finished building not only included a spacious study hall, but also dormitories, side rooms uses for various functions, a medical room and a library where thousands of volumes were kept.[2]

World War I

In 1904 Rabbi Naftoli Trop was invited to take up the position as Rosh yeshiva. His appointment ushered in the yeshiva's "golden era". Under his guidance the yeshiva grew and during the 1920s became one of the largest in Europe. From 1907 until 1910 the Mashgiach ruchani was Rabbi Yeruchom Levovitz who later joined the Mir Yeshiva.

After the outbreak of war between Germany and Russia in 1914, the Chofetz Chaim worried about the potential German occupation and the effect it would have on the yeshiva. There was also the threat of the town becoming severed from Russia and thus stemming its source of funding. In 1915 as the Russians retreated and the German army neared Raduń, the decision was taken that the yeshiva would be split into two parts. One would stay in Raduń and the second would move further inside Russia. Most of the students including the Chofetz Chaim, his son-in-law and Rabbi Trop left Raduń, while the minority remained with Rabbi Moshe Landynski and the Mashgiach ruchani Rabbi Yosef Leib Nendik. The second part of the yeshiva settled in Smilovitz in the Province of Minsk. In 1916 a new refuge was sought as the battle-line drew closer and the yeshiva moved further into Russia, to Shumyatz in the Province of Mohilov and latter to Snovsk in the Province of Chernigov. German forces occupied Minsk in February 1918. It was a turbulent period with the authorities arresting students who were freed only after much effort and expense. With the rise of communism the situation was not set to improve. After the authorities made it impossible for the yeshiva to survive in Russia the yeshiva looked to Poland and towards Raduń. The move back to Raduń was hastened with the death of Rabbi Hersh Leib Levinson in 1921 after a short illness.[1]

Return to Raduń

After encountering difficulties in obtaining permission to travel and cross the border into newly independent Poland, the yeshiva was delayed in Minsk for around two months. When permission was finally granted the yeshiva arrived in Baranowitz and where they stayed for a few days. In the spring of 1921 the yeshiva arrived back to Raduń. Rabbi Moshe Landynski was at the train station to greet the returnees. It was a joyous occasion, however their joy was short lived. When they arrived back at the yeshiva they found the inside of the building destroyed and abandoned. The Germans had confiscated the building for use as a horse stable and ammunition store, forcing the students to occupy the local Beth midrash. The windows were smashed and the furniture gone. The only option was to utilise the building as it stood and begin efforts to refurbish it. With time, the return of the yeshiva to it home endowed it with a new lease of life under the leadership of both Rabbi Naftoli Trop and Rabbi Moshe Landynski. Rabbi Levinson's son Yehoshua became supervisor and his son-in-law Eliezer Kaplan the Mashgiach ruchani.[2]

With the passing of Rabbi Trop in 1928, the prominence of the yeshiva slowly diminished. Even with the appointment of two young Rosh yeshivas, Rabbi Baruch Feivelson (Trop's son-in-law) and Rabbi Mendel Zaks (son-in-law of the Chofetz Chaim), the yeshiva would never fully regain its famed status.

Upon the death of Rabbi Baruch Feivelson in 1933, Rabbi Mendel Zaks became the sole Rosh yeshiva. Rabbi Avraham Trop also gave lectures in his fathers style which proved popular with the older students. The institution also included a kollel, which focused on the study of Kodashim. Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman and Rabbi Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman were among those who studied there.

Although the Chofetz Chaim rarely gave lectures in the yeshiva and never held the position of Rosh yeshiva, he was its driving force. When he died in 1933, the continued funding of the academy became an issue. Rabbi Moshe Landynski was forced to travel as far away as London to solicit funds. Rabbi Landynski himself died a few years later in 1938 aged 77.

World War II

With the outbreak of World War II the Soviet Union took Raduń. The majority of the yeshiva transferred to Vilna, Lithuania, while a few remained behind in Raduń, including the Chofetz Chaim's nephew-in-law Rabbi Mordechai Dov Roitblatt, Rabbi Hillel Ginsburg, brother-in-law of Eliezer Zev Kaplan, and Rabbi Avraham Trop. When conditions in Vilna became too crowded, the yeshiva decided to split in two again, with one half locating to Eishyshok under Yehoshua Levinson and the other to Otian. When the Soviets took Lithuania, the yeshiva ceased functioning. Although much effort was made in trying to enable the yeshiva to escape, only a few individuals were able to obtain visas and emigrate.[1]

Re-establishment in the United States

After World War II, Rabbi Mendel Zaks re-established the yeshiva in the United States. He was later joined by his son Rabbi Gershon Zaks. Reb Gershon was a student of Rabbi Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik, the "Brisker Rov". In the early 1960s the yeshiva moved to Tallman, New York, (now part of Suffern, New York). After the death of Rabbi Mendel Zaks in 1974, his son Rabbi Gershon Zaks inherited his position until his death in 1990. Today, descendants Rabbi Yisroel Mayer Zaks and Rabbi Aryeh Zev Zaks head the yeshiva.

A branch, called Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim Kiryas Radin is on a campus in nearby Monsey, New York.

Re-establishment in Israel

The son of Rabbi Moshe Landynski settled in Netanya, Israel where he also established a yeshiva in memory of Radun. In 2005, it had a student roll of 100 boys aged 17–22. The current rosh yeshiva is Rabbi Menachem Dan Meisels, a student of Rabbi Baruch Mordechai Ezrachi. The yeshiva's ethos reflects the Slabodka approach.

Re-establishment in Radun

The former Yeshiva building in Radun housed a theatre and a bar for many years, and as of 2018, is in a general state of disrepair. Plans are being made to renovate the building and to have it restored as a yeshiva for students from Russia and Israel.[3]

Notable alumni

- Rabbi Meyer Abovitz

- Rabbi Samuel Belkin

- Rabbi J. David Bleich

- Rabbi Yerucham Gorelik

- Rabbi Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman

- Rabbi Dovid Leibowitz

- Rabbi Yechezkel Levenstein

- Rabbi Naftoli Shapiro

- Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman

- Rabbi Gershon Yankelewitz

- Rabbi Mordechai Savitsky

References

- (Hebrew) Zariz, David. "Yeshivat Radin". Daat. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- Yoshor, Moses M. (September 1997). "A New Yeshiva Building". The Chafetz Chaim. Brooklyn, New York: Mesorah Publications, Ltd. p. 347. ISBN 0-89906-462-0.

- Gershon Hellman (Feb 14, 2018). "Returning to Radin". Ami Magazine. No. 355. pp. 50–52.