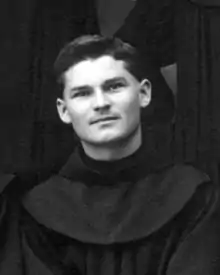

Radoslav Glavaš (junior)

Radoslav Glavaš (29 October 1909 – June 1945) was a Herzegovinian Croat Franciscan who headed the Department of Religion of the Ministry of Justice and Religion of the fascist Independent State of Croatia during the World War II.

Radoslav Glavaš | |

|---|---|

| |

| Head of the Department of Religion of the Ministry of Justice and Religion of the Independent State of Croatia | |

| In office 15 May 1941 – 15 May 1945 | |

| Prime Minister | Ante Pavelić (1941–43)Nikola Mandić (1943–45) |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Andrija Glavaš 29 October 1909 Drinovci, Grude, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | June 1945 (aged 35) Zagreb, Croatia, Yugoslavia |

| Cause of death | Executed by Yugoslav Partisans |

| Nationality | Croat |

| Alma mater | Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | July 1933 |

A native of Drinovci near Grude in Herzegovina, Glavaš became a member of the Franciscan Province of Herzegovina in 1928. After finishing his studies at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, he taught the Croatian language and literature at the Franciscan gymnasium in Široki Brijeg. Known as a nationalist, he supported the puppet Independent State of Croatia (NDH), established by Nazi Germany and Italy in 1941. He became head of the Department of Religion at the Ministry of Justice and Religion of the NDH immediately after the establishment of the puppet state in May 1941 and held that post until the dissolution of the NDH in May 1945.

He used his position to favor the Franciscan Province of Herzegovina, enabling the state sponsorship of its schools and state-controlled collection of financial revenues for the Franciscans. Despite the opposition from the Catholic Church, he enabled the establishment of the Franciscan Faculty of Theology in Sarajevo by the fascist government. Glavaš also used his position to oppose the appointment of Petar Čule, a secular priest, as bishop of Mostar-Duvno, a position previously held by the Franciscans.

He was executed by the Yugoslav Partisans for collaborating with the fascist regime in June 1945.

Early life

Glavaš was born in Drinovci near Grude in the region of Herzegovina, at the time part of Austria-Hungary, to father Petar and mother Mara née Marinović. He was christened as Andrija by parson in Drinovci friar Vjenceslav Bašić. His baptismal godfather was Ivan Glavaš. Glavaš finished elementary school in Drinovci in 1921.[1]

Afterward, Glavaš attended the Franciscan gymnasium in Široki Brijeg as an "internal" student, that is to become a priest and a monk. After finishing the sixth grade in 1927, Glavaš paused his education and entered a one-year novitiate at the Franciscan friary in Humac, Ljubuški on 29 June 1927. He changed his name to Radoslav and was ordained a monk by Lujo Bubalo. He returned to the gymnasium to finish the remaining two grades and graduated on 24 July 1930. Glavaš took his monastic vows in front of Provincial Dominik Mandić on 1 July 1928 and solemn vows on 3 July 1931, also in front of Mandić.[2]

After finishing his high-school education, Glavaš enrolled at the Franciscan seminary in Mostar in 1930, where he studied until 1932. He continued his education in Lille, France. As he was not yet 24 years old, Glavaš asked Mandić to obtain permission for his premature priestly ordination. Mandić asked the Pope for permission for Glavaš to be ordained on 19 May 1933, which Pope granted. Glavaš was ordained a priest in Fontenoy, and Mandić was notified about the ordination on 17 July 1933. Glavaš remained in Lille another year and asked to return to Herzegovina, which was granted by Provincial Mate Čuturić on 1 July 1934.[3]

After returning to Herzegovina, Glavaš served as a chaplain in Široki Brijeg from 1934 to 1935. He was then sent to study Croatian at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, after which he was supposed to return to the Franciscan gymnasium in Široki Brijeg to teach Croatian. As Herzegovinian Franciscans didn't own any accommodation in Zagreb, they lived in the monasteries of other Franciscan Provinces. Thus, Glavaš lived in the friary of the Croatian Franciscan Province of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Kaptol, Zagreb. Glavaš encountered several problems while living there, as he saw the statutory provisions and living style of these Franciscans as redundant and unnecessary and refused to wear the friar's clothes. The next year, the guardian of the Franciscan friary in Kaptol informed Čuturić that they cannot accommodate Glavaš anymore. Čuturić took up for Glavaš and asked the Zagreb Provincial Mihael Troha and the guardian of the friary to at least probe Glavaš until Christmas. His petition was accepted in October 1935, and Glavaš continued to live in Kaptol.[4]

However, Troha again complained about Glavaš to Čuturić in 1938, informing him that Glavaš leaves the friary at whim and often returns after midnight. Čuturić requested that Glavaš returns to Mostar. Glavaš left Zagreb for Mostar in December 1938. In the meantime, the two Provincials agreed that Glavaš would continue his studies at the friary near Zagreb in Jaska. Glavaš finished all of his exams on 27 June 1939 and remained in Jaska until July. During the studies, Glavaš became a prominent nationalist and anti-communist amongst the students, and while studying met Mile Budak, a prominent Ustaše and later a member of the World War II fascist Government of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH). Glavaš wrote positive critiques of Budak's literal work. Glavaš spent vacations in Austria in 1936 and Germany in 1937 to learn German.[5]

Čuturić asked him to return to Široki Brijeg to teach Croatian already in 1938, however, Glavaš asked him to prolong his studies. As he was preparing his doctoral thesis on Jakša Čedomil, a Catholic priest from Split, he asked Čuturić to ask the Franciscan friary in Dobro near Split to allow him to live there, as the majority of material about Čedomil could be found only in Split. His request was granted so he moved there in July 1939. He asked to remain in Dobro for an additional semester to finish his doctoral studies, however, Čuturić already appointed him professor in the Franciscan gymnasium in Široki Brijeg in April 1939 and refused his request. Thus, in September 1939, Glavaš started to lecture the Croatian language and literature in Široki Brijeg. This stalled his doctoral studies, so he defended his doctoral thesis only in 1942.[6]

Independent State of Croatia

In 1940 and early 1941, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria all agreed to adhere to the Tripartite Pact and thus join the Axis. Hitler then pressured Yugoslavia to join as well.[7] The Regent, Prince Paul, yielded to this pressure and declared Yugoslavia's accession to the Pact on 25 March 1941.[8] This move was highly unpopular with the Serb-dominated officer corps of the military and some segments of the public: a large part of the Serbian population, as well as liberals and Communists.[9] Military officers (mainly Serbs) executed a coup d'état on 27 March 1941, and forced the Regent to resign, while King Peter II, though only 17, was declared of age.[10] Upon hearing news of the coup in Yugoslavia, on 27 March Hitler issued a directive, which called for Yugoslavia to be treated as a hostile state.[11] The Germans started an invasion with air assault on Belgrade on 6 April 1941.[12] On 10 April 1941, the two Axis Powers, Germany and Italy, established its puppet Independent State of Croatia (NDH).[13]

The establishment of the NDH was welcomed amongst the professors of the Franciscan gymnasium in Široki Brijeg. Glavaš openly supported the newly established fascist regime. However, the gymnasium's administration sanctioned political outbursts amongst its students, with many students being expelled because of their political activity.[14]

Budak became Minister of Justice and Religion of the newly established NDH and asked the Herzegovinian Provincial Krešimir Pandžić on 10 May 1941 to allow Glavaš to become a member of his ministry. Pandžić accepted the request five days later. Glavaš was appointed the head of the Department of Religion at the Ministry.[15]

With the new position, Glavaš, taught by his own experience, bought the house where Herzegovinian Franciscans could live in Zagreb in 1942.[16] The Herzegovinian Franciscans also used his position to equalise the status of the Franciscan schools with the public schools and to secure the financing for their schools from the state treasury, to become independent from their dioceses and the bishops.[17][18]

Glavaš also initiated the state-sponsored establishment of the Franciscan Faculty of Theology in Sarajevo for all the Franciscan Provinces in the NDH in 1944. This initiative was opposed by the Church authorities, who insisted that such an educational institution must be established and approved by the Church. Archbishop Aloysius Stepinac of Zagreb wrote against such a move, complaining that the church authorities must not be bypassed. Archbishop Ivan Šarić was also "seriously surprised" by the state establishment of the faculty without the church approval. However, the Franciscans claimed that they have a right to establish the faculty without the church's approval.[19]

He was executed by the Yugoslav Partisans after the liberation of Zagreb, either in May or June 1945. The Franciscans used this opportunity and with the help from Glavaš equalised the status of Franciscan schools with the public schools.[17]

Notes

- Jolić 2008, p. 192.

- Jolić 2008, p. 193.

- Jolić 2008, pp. 194-195.

- Jolić 2008, pp. 195-196.

- Jolić 2008, pp. 196-202.

- Jolić 2008, pp. 199-200.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 34.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 39.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 41.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 43–47.

- Trevor-Roper 1964, p. 108.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 67–68.

- Vukšić 2006, p. 221.

- Mandić 2019, p. 219.

- Jolić 2008, pp. 202-203.

- Jolić 2008, pp. 195, 206.

- Mandić 2019, p. 222.

- Jolić 2008, pp. 203-204.

- Jolić 2008, pp. 207-208.

References

Books

- Ciglić, Boris; Savić, Dragan (2007). Dornier Do 17, The Yugoslav Story: Operational Record 1937–1947. Belgrade: Jeroplan. ISBN 9788690972708.

- Mandić, Hrvoje (2019). "Izbačeni učenici Širokobriješke gimnazije u razdoblju od 1941. do 1944. godine". In Akmadža, Miroslav; Grubišić, Vinko; Krešić, Katica; Marić, Ante; Ševo, Ivo; Šteko, Miljenko; Vasilj, Marija (eds.). Zbornik radova s međunarodnoga znanstveno-stručnog skupa u povodu 100. obljetnice Franjevačke klasične gimnazije s pravomjavnosti na Širokom Brijegu [Expelled students of the Široki Brijeg gymnasium in the period from 1941 to 1944] (in Croatian). ISBN 9789958370915.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804708579.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1964). Hitler's War Directives: 1939–1945. Viborg: Norhaven Paperback. ISBN 1843410141.

Journals

- Jolić, Robert (2008). "Fra Radoslav Glavaš (1909. - 1945.)" [Friar Radoslav Glavaš (1909 - 1945)]. Hercegovina Franciscana (in Croatian). 4 (4): 191–242.

- Vukšić, Tomo (2006). "Mostarski biskup Alojzije Mišić (1912.-1942.) za vrijeme Drugog svjetskog rata" [Bishop of Mostar Alojzije Mišić (1912-1942) during the Second World War]. Crkva U Svijetu (in Croatian). 41 (2): 215–234.