Ralph Barton

Ralph Waldo Emerson Barton (August 14, 1891 – May 19, 1931) was an American artist best known for his cartoons and caricatures of actors and other celebrities. Though his work was heavily in demand through the 1920s and is often considered to epitomize the era, his personal life was troubled by mental illness, and he was nearly forgotten soon after his suicide, shortly before his fortieth birthday.[1]

Ralph Barton | |

|---|---|

Ralph Barton in 1926 | |

| Born | Ralph Waldo Emerson Barton August 14, 1891 |

| Died | May 19, 1931 (aged 39) |

| Occupation | Artist |

| Spouse(s) | Marie Jennings Anne Minnerly Carlotta Monterey Germaine Tailleferre (m. 1926-1927) |

| Children | Natalie Barton Diana Barton |

Early life

Ralph Barton was the youngest of four children born to Abraham Pool and Catherine Josephine (Wigginton) Barton.[2][3] His father was an attorney by profession, but around the time of Ralph's birth made a career change to publish journals on metaphysics. His mother, an accomplished portrait painter, ran an art studio.[4] The young Barton showed his mother's aptitude for art, and by the time he was in his mid-teens he had already seen several of his cartoons and illustrations published in The Kansas City Star and the Kansas City Journal-Post. Buoyed by this success, in 1908 Ralph Barton dropped out of Kansas City's Westport High School before graduating. He moved to Chicago in 1909 to attend the Art Institute of Chicago, but soon found he didn't "like Chicago or Chicago people and worst of all the art institute. I could learn twice as much at work" he confided in a letter to his mother.[4] Returning to Kansas City within a matter of months, he married his first of four wives, Marie Jennings.

Career

While back in Kansas City Barton resumed his work for the Star and Journal-Post to support his wife and daughter, born in 1910. His first break, or national exposure, came in 1912 when Barton sold an illustration to the humor magazine Puck. Encouraged, the Bartons moved to New York City, where Ralph found steady work with Puck, McCall's and other publications. His wife was not happy with life in the Big Apple however, and returned to Kansas City within a few months. Barton rented studio space, which he shared with another famous Missouri artist, Thomas Hart Benton, and the two became fast friends.[4] It was Benton in fact who served as the subject of Barton's first caricature.[1]

In 1915 Puck magazine sent Barton to France to sketch scenes of World War I. It was then that Barton developed a great love of all things French, and throughout his life he would return to Paris to live for periods of time. In 1927 the French government awarded Barton the Legion of Honour[4]

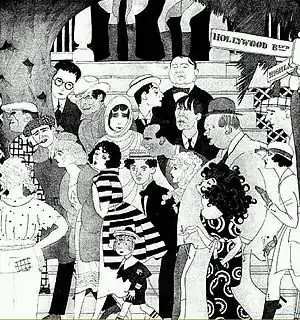

Barton's first caricature was of Thomas Hart Benton; his last, of Charlie Chaplin.[1] In between he knew everyone and drew everyone in the social and cultural scene of New York. Some of his most famous works were group drawings, and perhaps the most noted was a stage curtain created for a 1922 revue, depicting an "audience" of 139 faces looking back at the real theater-goers. "The effect was electrifying, and the applause was great," said another caricaturist of the era, Aline Fruhauf.[6]

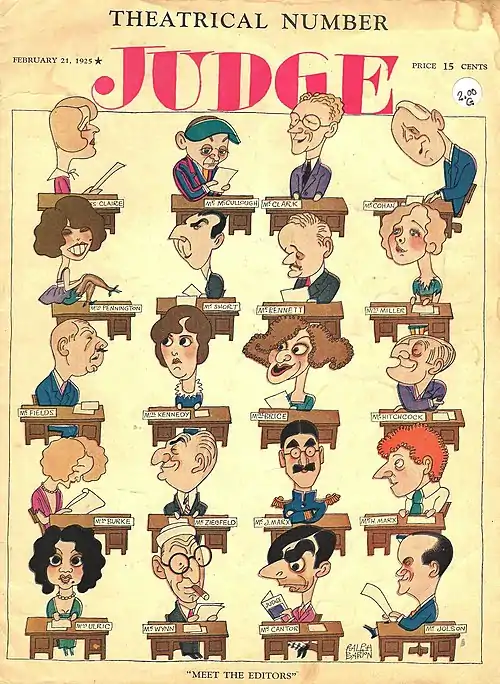

Much of Ralph Barton's work from the mid-1920s onward was for The New Yorker magazine, which he joined as an advisory editor from its very beginning in 1924. He would also be a stockholder in the publication. Other prominent magazines of the era to feature his work were Collier's, Photoplay, Vanity Fair, Judge, and Harper's Bazaar. While many would be published unsigned, there was no mistaking Barton's unique style.[7] Ralph Barton would illustrate one of the 1920s most popular books, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. With the urging of friend Charlie Chaplin, Barton also made one movie, Camille. The short film featured such notables as Paul Robeson, Ethel Barrymore, and Sinclair Lewis.[7]

At the height of his popularity, Barton enjoyed not only the acquaintance of the famous, but a solid and impressive income. All of this concealed a terribly unhappy life. He was beset by manic-depressive disorder, and each of his four marriages ended in divorce. (One of his wives was the French composer Germaine Tailleferre (1892–1983) who was a member of Les Six.) A self-portrait, painted around 1925 and modeled on an El Greco, shows a drawn and unhappy figure. A year later he wrote, "The human soul would be a hideous object if it were possible to lay it bare."

Death

On May 19, 1931, in his East Midtown Manhattan penthouse apartment, Barton shot himself through the right temple. He was 39 years old.[8] His suicide note said he had irrevocably "lost the only woman I ever loved" (the actress Carlotta Monterey had divorced Barton in 1926 and married Eugene O'Neill in 1929), and that he feared his worsening manic-depression was approaching insanity.[9] He wrote: "I have had few difficulties, many friends, great successes; I have gone from wife to wife and house to house, visited great countries of the world—but I am fed up with inventing devices to fill up twenty-four hours of the day."[10] Almost immediately, his reputation dropped from sight; several years after his death, a caricature of George Gershwin sold for a mere $5.[1] Ralph Barton's ashes were returned to his native Kansas City and interred in Mount Moriah Cemetery.[4]

Legacy

Toward the end of the century, his work was included in several exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery. A 1998 conference on cartooning at the Library of Congress also considered his work.

Bibliography

Books

- G.P.P., ed. (1922). Nonsenseorship : sundry observations concerning prohibitions, inhibitions and illegalities. Illustrated by Ralph Barton. New York: G. P. Putnam's sons/The Knickerbocker Press.

- Loos, Anita (1925). "Gentlemen prefer blondes" : the illuminating diary of a professional lady. Intimately illustrated by Ralph Barton. New York: Boni & Liveright.

- — (1927). But gentlemen marry brunettes. Intimately illustrated by Ralph Barton. New York: Boni & Liveright.[11]

- Shaw, Charles G. (1927). Heart in a hurricane. Illustrations by Ralph Barton. New York: Brentano's.

- Merkin, Richard (1968). The jazz age, as seen through the eyes of Ralph Barton, Miguel Covarrubias, and John Held, Jr. Providence, R.I.: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design. Exhibition catalog.

Essays and reporting

- R. B. (March 7, 1925). Illustrated by Ralph Barton. "Black magic in West Forty-Fifth Street : Mr. James Rennie and Mr. Francis Corbie in "Cape Smoke" at the Martin Beck Theatre". The New Yorker. 1 (3): 10.

- Barton, Ralph (March 7, 1925). Illustrated by Ralph Barton. "La Ville Lumière". The New Yorker. 1 (3): 19.

- R. B. (March 14, 1925). Illustrated by Ralph Barton. "Ibsen done right by at last : great work by The Actors' Theatre in Forty-Eighth Street". The New Yorker. 1 (4): 12.

- — (March 21, 1925). Illustrated by Ralph Barton. "Idyllic moments from the current theatre : Miss Doris Keane and Mr. Leon Errol stub their several toes". The New Yorker. 1 (5): 15.

- — (March 28, 1925). Illustrated by Ralph Barton. "Glorifying the American guffaw : a new edition of the Follies that really is new". The Theatre. The New Yorker. 1 (6): 15.

- — (April 4, 1925). Illustrated by Ralph Barton. "The Actors' Theatre's third knock-out : bring your lunch and remain in your seats to see "The Wild Duck"". The Theatre. The New Yorker. 1 (7): 15.

References

- "Abstracts for Caricature and Cartoon in Twentieth-Century America". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- Updike, John (1989-02-13). "A Case of Melancholia". The New Yorker (Serial). ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Updike, John (February 20, 1989). "A Case of Melancholia". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- Dictionary of Missouri Biography, Lawrence O. Christensen, University of Missouri Press, 1999

- "When the Five O'Clock Whistle Blows in Hollywood". Vanity Fair. September 1922. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "Ralph Barton theater curtain". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 2008-01-29. from the exhibition Celebrity Caricature in America: Stage Folk

- "Ralph Barton biography". Princeton University Library website. 2010. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- "Ralph Barton: Self-portrait". National Portrait Gallery. Archived from the original on 2008-05-29. Retrieved 2008-01-29. from the exhibition Eye Contact: Modern American Portrait Drawings from the National Portrait Gallery

- "Ralph Barton Ends His Life With Pistol". The New York Times. May 21, 1931. p. 1

- Zuck, Roy B. (2009). The Speaker's Quote Book: Over 5,000 Illustrations and Quotations for All Occasions. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Academic & Professional. p. 129. ISBN 9780825441660.

- Library of Congress catalog has 1928 for year of publication - see https://lccn.loc.gov/28014706

External links

Media related to Ralph Barton at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ralph Barton at Wikimedia Commons- Works by Ralph Barton at Project Gutenberg

- Ralph Barton at IMDb

- Exhibition of Drawings for Contes Drolatiques of Balzac, an exhibition catalog available from the Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, containing descriptive information about the artworks.