Ramgarhia

The Ramgarhia are a community of Sikhs from the Punjab region of northwestern India, encompassing members of the Lohar and Tarkhan subgroups.[1]

Etymology

Originally called Thoka, meaning carpenter,[2] the Ramgarhia are named after Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, whose birth name of Thoka became Ramgarhia in the 18th century when he was put in charge of rebuilding of what became known as Ramgarhia Bunga, at Ramrauni, near Amritsar. He rose from being a carpenter to the leader of a misl bearing the Ramgarhia name.[3][4]

Occupation and status

Ramgarhias traditionally mostly carpenters but included other artisan occupations such as stonemasons and blacksmiths.[3] Generally, Sikh carpenters use Ramgarhia as a surname whereas Hindu carpenters use Dhiman.[5]

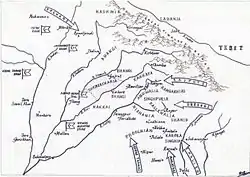

Their artisan skills were noted by the British, who encouraged many Ramgarhia to move to colonies in East Africa in the 1890s, where they assisted in the creation of that region's infrastructure and became Africanised.[3] One significant project in which they and other Punjabi Sikhs were involved was the cion of the railway linking the present-day countries of Kenya and Uganda, which was completed in 1901.[6]

The British authorities also encouraged Ramgarhias to migrate within India during the first quarter of the 20th century. Their inventiveness and skills at construction, repair and maintenance were of much use at, for example, the tea plantations in Assam.[7] Now distant from their landlords in Punjab, who were mostly Jat Sikhs, the Ramgarhia diaspora in the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam were able to enhance their social status even higher.[5][8] The lessons learned in Punjab, where they had established a few gurdwaras to aid community cohesion and had been loyal to the British and generally unwilling to support the Jat-led Akali movement, assisted their improved status in Assam.[9]

Despite Sikhism generally rejecting the caste system, it does have its own very similar socio-economic hierarchy, with its constituents often described as castes. In that, according to Peter Childs, the Ramgarhias today rank second.[10] However, Joginder Singh says that they still lack influence in the Punjab, which is a region heavily dependent on agriculture and dominated by some influential peasant farmers Jat,Saini but also some from communities such as the Labanas and Kambojs.Those people, says Singh, have "captured the control of Sikh socio-religious institutions and political parties." Associations representing the less influential but numerically superior people have formed in reaction to this, including Ramgarhia groups that are running their own educational and socio-religious institutions as well as mobilising their diaspora and any prominent individuals who might assist in enhancing their identity.[1]

References

- Singh, Joginder (2014). "Sikhs in Independent India". In Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis E. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-19100-411-7.

- Chopra, Pran Nath (1982). Religions and communities of India. East-West Publications. p. 184.

- Singha, H. S. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism. Hemkunt Press. p. 111.

- Saini, A. K.; Chand, Hukam. History of Medieval India. p. 146. ISBN 978-81-261-2313-1.

- Judge, Paramjit S. (1996). Strategies of Social Change in India. M. D. Publications. p. 54. ISBN 978-8-17533-006-1.

- Tatla, Darshan Singh (2014). "The Sikh Diaspora". In Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis E. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-19100-411-7.

- Banerjee, Himadri (2013). "The Other Sikhs: Bridging Their Diaspora". In Hawley, Michael (ed.). Sikh Diaspora: Theory, Agency, and Experience. BRILL. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-9-00425-723-8.

- Banerjee, Himadri (2013). "The Other Sikhs: Bridging Their Diaspora". In Hawley, Michael (ed.). Sikh Diaspora: Theory, Agency, and Experience. BRILL. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-9-00425-723-8.

- Banerjee, Himadri (2014). "Sikhs Living Beyond Punjab in India". In Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis E. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 538. ISBN 978-0-19100-411-7.

- Childs, Peter (2013). Encyclopaedia of Contemporary British Culture. Routledge. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-13475-554-7.